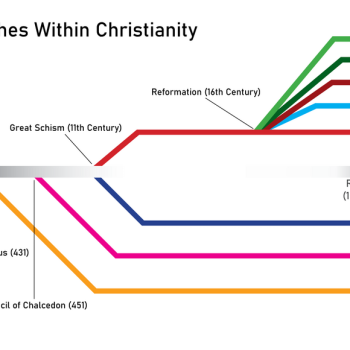

That post we had the other day about why there can be Calvinist Baptists but not Lutheran Baptists turned out to be part of a very interesting discussion in the Christian blogosphere. Superblogger Joe Carter wrote a post summarizing the various points in the debate. (He scored us the winner.)Joe Carter, from Debatable at the Gospel Coalition:

The Issue – What does it mean to be a Calvinist in a Baptist denomination? And why are there no ‘Lutheran Baptists’? Several evangelicals from various Reformed traditions have recently debated those questions. [Editor’s note: No, Joe! Lutherans are not a “Reformed tradition” in the way Baptists are. That’s my point! Oh, never mind.]

Opening Remarks – After hearing about the controversy over Calvinism in the Southern Baptist Convention, David Koyzis, a professor of political science at Redeemer University College in Ontario, Canada, asks why there are Calvinist Baptists but no ‘Lutheran’ Baptists:

From a historical vantage point, the reason for this difference between the Lutheran and Calvinist labels is far from obvious. After all, Calvin was much more explicit in setting forth a reformed ecclesiology than was Luther, who was more willing than his Genevan counterpart to tolerate different ecclesiastical polities in different geographical contexts. The Churches of Sweden and Finland, for example, maintained an episcopal polity with bishops in apostolic succession. Nevertheless, when Swedes and Finns migrated to North America, their respective transplanted church bodies, the Augustana and Suomi Synods, were generally less hierarchical and more congregational in nature, without in any way impairing their continued communion with the mother churches. Their common adherence to the Augsburg Confession was more important than their polities. On the other hand, when Reformed Christians established their churches in the New World, they usually brought their polity with them to this side of the Atlantic. Thus if Lutheranism has been historically more flexible than Calvinism with respect to ecclesiology, it is not immediately evident to some of us why becoming a Calvinist is usually thought to be a soteriological statement while becoming a Lutheran is an ecclesiastical one. But it may be that I’m missing something that others have picked up on.

Position #1 – Collin Garbarino, an assistant professor of history at Houston Baptist University, proffers an explanation for why we don’t have Lutheran Baptists:

When we speak of “Calvinist Baptists” we refer to Baptists who affirm Calvin’s soteriology. Why not call them Lutheran Baptists? Both reformers, Martin Luther and John Calvin, had similar doctrines of soteriology. (I know some people will disagree with that last statement, but those people are wrong.) My friend and colleague, Jerry Walls, has even called Thomas Aquinas a Calvinist. How does “Thomistic Baptists” sound? Why does Calvin get all the credit? The reasons are mostly historical. One should not underestimate the role of Calvin’s Institutes. Calvin created a handbook for faith and practice that helped transplant reformation into new contexts. While Luther’s writings are more entertaining, they aren’t systematic. If a Protestant has a question, chances are, the Institutes has an answer. Calvin’s writings affected the English-speaking Christians. The Westminster Divines injected Calvinism into the Anglican church. Various nonconformists and congregationalists began to drift away from the Anglicans. Their theology became a modification of a modified Calvinism. Some of these congregationalists became convinced that paedobaptism was illegitimate. They modified a modification of a modified Calvinism.

Position #2 – Greg Forster, author of The Joy of Calvinism, responds to Koyzis and Garbarino by giving several reasons other than the historical, including:

1) Calvinist (and consequently Arminian) theology is clearer. Our Lutheran brothers say that asking the big questions leads only to paradoxes, of which the lowly human mind cannot say much that is meaningful. Meanwhile, our Anglican brothers may have clear personal opinions about the answers to these questions, but when setting direction for the church at large they drape a graceful veil of ambiguity over them for the sake of unity. The confessional Calvinist finds this insufficient—not because he has a high opinion of human reason, but because he believes God has told us clearly and consistently what we are to believe regarding these questions, and the pastor must preach the whole counsel of God. Rising in response, the confessional Arminian agrees that God has told us what to believe, disagreeing only on what God has said. It seems to me that Baptist and Free Church communities generally require this level of clarity in their theology; a large-scale commitment to paradoxes and ambiguity in theology is only sustainable in the context of a broader coherence of tradition and culture that magisterial churches presuppose but Baptist churches do not.

Position #3 – Steven Wedgeworth, a founder and general editor of The Calvinist International, says the differences have a lot to do with how the labels are used:

The real reason that Calvin gets the “credit” is because 16th and 17th century polemics tended to place the blame on him. You see, “Calvinism” is all too often a signifier, not of Calvin’s systematic theology, nor of Reformed theology over and against Lutheranism (though it is that at times), but of the more Puritan and disciplinarian subset of Reformed theology which instigated many of the famous controversies of that time. Even predestinarian and sacramentarian “Anglicans” would at times distance themselves from the C-word for social and political reasons. Richard Hooker is the exemplar of this mood. Over time, however, the tag, implying narrow partisanship, was embraced and became a badge of pride and community. And likewise, “Lutheranism” doesn’t really signify Martin Luther himself nor his primary theological contributions. All of the “Reformed” and “Calvinist” theologians claimed Luther as their own. They all held to justification by faith alone, the freedom of the Christian, and the two kingdoms. Instead, “Lutheran” eventually became the trademark of the Gnesio-Lutherans who made their particular emphasis on the real presence in the elements the sin qua non of Lutheran identity. It really had not figured as such in Luther’s most foundational works, and its unwarranted primacy did in part serve to give Lutheranism a sort of clerical and disciplinarian character which was quite inimical to its original theology. English Christians, many of whom were quite “Lutheran” at the outset, eventually lost their connection to that title because of their own proximity to the “Reformed” wing of the Reformation and because of the Lutheran reaction against that wing. [Editor’s note: The real presence not an emphasis of Luther? Seriously? What happened at the Marburg Colloquy, which sent Lutherans and anti-Sacramental Protestants on their separate ways?]

Position #4 – Finally, a Lutheran weighs in. Gene Veith, explains why Lutheranism is not detachable from “Lutheran churches”:

The discussion shows the profound misunderstanding of Lutheran theology that drives us Lutherans crazy. Here we see on both sides of the issue the view that Calvinism is the same as Lutheranism except without the sacraments, which really don’t matter all that much so why can’t we just get along? To understand Lutheranism, it is necessary to recognize that the Lutheran understanding of salvation by grace and justification by faith cannot be separated from the Lutheran teachings of baptismal regeneration and the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine of Holy Communion. These teachings are all intimately connected with each other in Lutheran theology and spirituality. If you play them off against each other, thinking you can have Lutheran soteriology without Lutheran sacramental theology, you might have Calvinists or Baptists or Calvinist Baptists or something else, but you cannot have Lutherans. Nor can you have Lutheran Calvinists or Calvinist Lutherans or Lutheran Baptists or Baptist Lutherans.

Scoring the Debate: As an answer to Koyzis’ original question, I think Veith provides the clearest answer, at least to the part about why there are no Lutheran Baptists. The sacramental theology of Lutheranism is much more incompatible with Baptist theology than are other aspects of Reformed theology. But the true value of the discussion is not in answering the question but in getting people to think about why they align with a specific theological tradition. To be a Calvinist Baptist in 2013 (which I am) almost requires one to choose the tradition and to defend that choice to people who think such a category can’t even exist. The same isn’t necessarily true for Arminian Baptists (which I was for much of my life), since it is often considered the default position among baptists, particularly within the Southern Baptist Convention. The result is that Baptists—like most other Christians—too often accept the default setting of their local church’s theology (whether Calvinist, Arminian, etc.) without ever inquiring whether it fits with what they find in Scripture. Discussions like this one can help awaken us from our dogmatic slumbers and lead to us to thoughtfully reflect on why we choose the theological labels we do.

FURTHER UPDATE: Collin Garbarino tries to defend his contention that Luther’s soteriology and Calvin’s are the same. He does so by giving the Calvinist reading of Luther, that Luther is actually the same as Calvin, but later Lutherans followed Melanchthon by playing down predestination (which he shouldn’t have done), while rejecting Melanchthon’s wobbling on the real presence (which was correct and which Calvin followed, though the later Lutherans mistakingly did). We confessional Lutherans are really “gnesio-Lutherans,” rather than actual followers of Luther. You go to the site and answer him.