Sociologist of religion Peter Berger (an ELCA Lutheran) discusses the phenomenon of the Sunday Assembly, which we blogged about yesterday. He said the fact that atheists too are gathering together following the pattern of religious activities demonstrates the almost universal human need to worship (or the equivalent) and to join together with others who hold common religious or philosophical convictions.

In the course of his discussion, he draws on older sociologists who distinguish between different kinds of religious institutions: a church (which a person is born into) and a sect (which a person chooses to join). Such a distinction, it seems to me, grows out of the European state church. American religion, according to Dr. Berger, has added the concept of the denomination, which a person may be born into or choose freely to join. Dr. Berger further says that denominations of one sort or another–in the sense of “a community of value, religious or otherwise,” have become inevitable in America, extending even to atheists.

After the jump, read his argument and some questions I have about “non-denominational” churches.

It would seem that in American Christianity, a religious institution that you are born into is suspect, so that what the European scholars call “sects,” with derogatory implications, are more the norm in this country. But we also have “non-denominational” churches. How do they fit into this discussion? Taken together, do they have some common theology and practices that bind them together, even though they remain institutionally independent from each other? I know some of you readers go to non-denominational churches, and I’m curious about them. In allowing members to hold a variety of beliefs, do they baptize infants if the parents believe in that, or just adults, which would mean they have a particular theology after all similar to that of the Baptists. I’ve head of some congregations that to avoid controversies don’t baptize anyone at all. Or do non-denominational congregations have a theology, just belong to no trans-congregational organizations, in which case they still might be considered a denomination in Dr. Berger’s sense.

From Peter Berger, The Denominational Imperative | Religion and Other Curiosities:

Every community of value, religious or otherwise, becomes a denomination in America. Atheists, as they want public recognition, begin to exhibit the characteristics of a religious denomination: They form national organizations, they hold conferences, they establish local branches (“churches”, in common parlance) which hold Sunday morning services—and they want to have atheist chaplains in universities and the military. As good Americans, they litigate to protect their constitutional rights. And they smile while they are doing all these things.

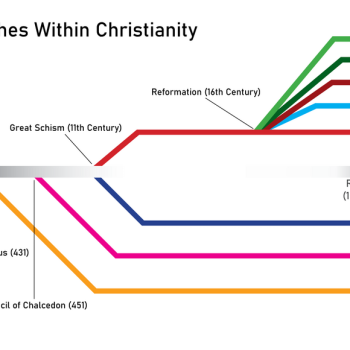

As far as I know, the term “denomination” is an innovation of American English. In classical sociology of religion, in the early 20th-entury writings of Max Weber and Ernst Troeltsch, religious institutions were described as coming in two types: the “church”, a large body open to the society into which an individual is born, and the ”sect”, a smaller group set aside from the society which an individual chooses to join. The historian Richard Niebuhr, in 1929, published a book that has become a classic, The Social Sources of Denominationalism. It is a very rich account of religious history, but among many other contributions, Niebuhr argued that America has produced a third type of religious institutions—the denomination—which has some qualities derived from both the Weber-Troeltsch types: It is a large body not isolated from society, but it is also a voluntary association which individuals chose to join. It can also be described as a church which, in fact if not theologically, accepts the right of other churches to exist. This distinctive institution, I would propose, is the result of a social and a political fact. The denomination is an institutional formation seeking to adapt to pluralism—the largely peaceful coexistence of diverse religious communities in the same society. The denomination is protected in a pluralist situation by the political and legal guarantee of religious freedom. Pluralism is the product of powerful forces of modernity—urbanization, migration, mass literacy and education; it can exist without religious freedom, but the latter clearly enhances it. While Niebuhr was right in seeing the denomination as primarily an American invention, it has now become globalized—because pluralism has become a global fact. The worldwide explosion of Pentecostalism, which I mentioned before, is a prime example of global pluralism—ever splitting off into an exuberant variety of groupings.

The British sociologist David Martin has written about what he called the “Amsterdam-London-Boston axis”—that offspring of the Protestant Reformation that did not eventuate in state churches—the free churches, all voluntary associations, which played an enormous role in the British colonies in North America and came to full fruition in the United States. This form of Protestantism has pluralism in its sociological DNA. One could say that it has a built-in denominational imperative: “Go forth and multiply”. American Protestant history is one of churches splitting apart, merging, splitting apart again. Churches have divided over doctrinal differences, ethnic or regional ones, or because of moral or political differences. Almost all Protestant churches split over the issue of slavery in the 19th century, as they divide now over what I call issues south of the navel. American Lutheranism was for a long time split into ethnically defined synods, though this has now been replaced by basic doctrinal disagreements. Roman Catholicism has been protected from Protestant denominationalism by its centralized hierarchy, but it has become “Protestantized” in a different way: Against its deepest ecclesiological instincts, it has become de facto a voluntary association—with the result that its lay people have become vocally uppity. Even American Jews have organized in at least four denominations. (Joke: An American Jew stranded on a desert island built two synagogues, one in which he goes to pray, the other in which he would not be found dead), Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus in America have all fallen into the denominational pattern. The same pattern appears in secular movements (for example, the various “denominations” of American psychotherapy). Even witches have managed to create a denomination, Wiccan (I understand that they want the right to appoint chaplains for hospitals or in the military). Why should atheists be an exception?