The cultural influence of the Reformation is getting lots of attention on this 500th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses. But the topic is often treated with a theological ignorance that is surprising to find in works of scholarship.

The Nation has a long article on the subject, quoted and linked after the jump, which is essentially a review essay of several new books on Luther and Protestantism. As the article observes, the Reformation is often credited or blamed for opposite influences: for a new personal piety and for the rise of secularism; for recovering the Bible and for launching modernity; for the rise of individualism and for the rise of the nation state; for inventing freedom and for capitalist oppression, etc., etc.

The article by Elizabeth Bruenig, drawing on the books she is reviewing, says that what Luther did was to make religion a private, inward matter. Whereas the external world–including the state, the society, the economic order–was irrelevant spiritually. Therefore, it was allowed to run along on its own without a religious context (as in Catholicism). Thus the rise of secularism, modernity, science, and a world that does not need to consider God.

Meanwhile, the inner spiritual life that Luther encouraged had the additional effect of questioning all external authority, making a space for freedom and undermining institutions, which also had a secularizing and eventually revolutionary effect.

But this analysis, while citing Luther’s doctrine of the Two Kingdoms, completely misunderstands what it means–to the point of interpreting it to mean its opposite. And it utterly ignores one of Luther’s greatest and most culturally influential theological contributions, the place where he directly addressed the value of the “secular” realm and to the role it plays in the Christian’s faith; namely, his doctrine of vocation.

What other examples of theological illiteracy do you see in this article? (Hint: Did Luther really teach a theology based on inwardness, with individuals going inside themselves for a purely interior relationship with God?)

The Two Kingdoms does NOT teach “the kingdom of God” vs. “the kingdom of secular politics,” as the article states. Rather, God is the King of both kingdoms! Both the Heavenly Kingdom and the Earthly Kingdom are ruled by God. But they are to be distinguished from each other.

God rules them both in different ways and Christians, who are citizens of both kingdoms, live in them in different ways. God is hidden in the Earthly Kingdom, where He providentially cares for His whole creation, including those who do not know Him. He rules it by His moral Law, which is applicable in the world and remains a standard by which earthly rulers and institutions can be judged. And Christians are to do good works in the world–to work for justice, care for the poor, and battle the evils that are part of the fallen human condition.

In the Heavenly Kingdom, in contrast, God is revealed, and Christians are under the Gospel of God’s grace and the forgiveness of sins through faith in Christ.

But then God sends Christians out into the world to live out their faith in their worldly vocations. Not just their economic work, but their callings in the family, the church, and the state. (Luther’s theology of the three estates should also be a part of any discussion of the Reformation teaching about culture.)

In all of their vocations, Christians are to love and serve their neighbors. Vocation is the place of good works. Also spiritual growth, as Christians endure the trials and tribulations that their vocations bring. Here they co-operate with God as He governs His world.

Far from being dualistic, as these studies assume, Luther’s theology brings these realms together, which had been separated by monasticism and the Catholic position that spiritual perfection requires vows of celibacy (rejecting the estate of the family), poverty (rejecting full participation in the economy), and obedience (in which the “religious” person had to obey the laws of the church but was exempt from the authority of the state).

Luther’s theology did open up the “secular” realm, but he did it by, in effect, making it “spiritual”–insisting on God’s presence and providential care in the world and making it the arena for Christian life.

The Nation article says nothing about the cultural influence of the doctrine of vocation, also known as the “priesthood of all believers.” One result was universal education. The breakdown of medieval religious and eventually social hierarchies in the name of Christian equality before God. Social mobility, as education and the spiritually-motivated work ethic contributed, if not to the theory of capitalism, to the accumulation of wealth on the part of former peasants.

The Reformation did lead to a new concept of freedom based on the freedom that came from the Gospel. It did lead to a new valuation of the world and social pursuits, but it did so because it gave that valuation and those pursuits a religious motivation.

Yes, Protestantism soon took many different forms, each with influences of its own.

But one shouldn’t write about Luther’s cultural influence without attention to the influence of Luther’s theology of culture.

From Elizabeth Bruenig, Martin Luther’s Revolution, The Nation:

Theology is morality is politics is law—and whether or not it’s immediately obvious, the world is steeped in theology. In contemporary America, and especially in the more secular precincts of Western Europe, it seems unlikely that one could look at a property deed or a government budget and find, just beneath its explicit reasoning, traces of old theological disputes and their resolutions. But they’re there, and examining them offers a view of what might have been, had history—in particular, the Protestant Reformation, ignited 500 years ago this October by a German monk named Martin Luther—unfolded differently. . . .

This paradox—that the Reformation could birth a peasant revolt while its instigator rallied behind the princes—is a picture of Protestantism’s confusing political legacy in miniature. Protestantism arguably brought about many of the preconditions for the Enlightenment and liberalism, and at the very least introduced Europe to a headier skepticism of authority than had prevailed before. (Indeed, Roper credits the Reformation with sparking the secularization of the West.) On the other hand, the release of significant portions of life—namely politics and economics—-from the purview of religious authority may have expanded certain freedoms, but it didn’t result in a betterment of conditions for the most disadvantaged, even as it helped transform the Christian message into something far more internal and private than that of the earlier Church.

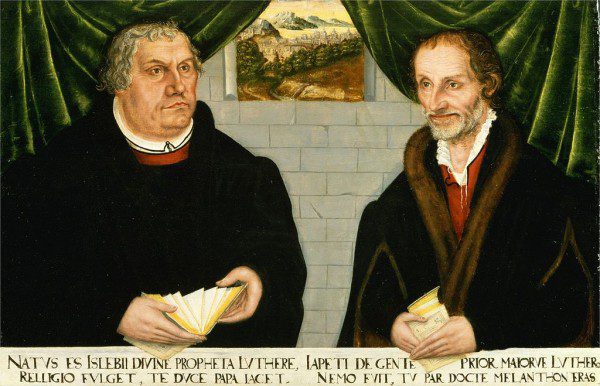

Painting of Luther and Melanchthon, attributed to Lucas Cranach the Younger [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons