You want to read a good Christmas book? You can’t do better than the one I am reading. It’s by St. Athansius, and it’s entitled On the Incarnation of the Word.

The edition I linked to has as an introduction by C. S. Lewis, which has been published separately as his illuminating essay On Reading Old Books, which shows how reading works from the past can give us a new perspective by freeing us from the blinders of our own day. That is certainly true of this “old book,” written in 335 A.D.

St. Athanasius here is exploring and applying what the Gospel of John teaches about the Son of God as “the Word.” The evangelist writes, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1).

The word–that is, the logos–was an important concept in Greek philosophy. In that context, it refers to the order, design, and meaning of the universe. Logos gives us the word “logic,” and is the foundation of rationality. That mental processes, such as logic, apply to the universe outside of the self is evidence that there is a common rationality, the logos, that underlies them both.

That the Greeks expressed this concept in terms of language–the “word”–is remarkably prescient, as contemporary philosophers have been showing that language is foundational to all thought and as contemporary scientists have been showing that the foundations of the natural world, from the laws of physics to the D.N.A. of living organisms have the qualities of language.

St. John takes the logos even further than the classic philosophers. He describes “the Word” as something like the Mind of God–God’s logic, God’s ideas, God’s self-conscious mental awareness. Thus, “All things were made through [the Word], and without him was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:3). And eventually, with Jesus Christ, “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1: 14).

St. Athanasius writes about the Word being the agent of Creation, and then how that same Word became the agent of Redemption. He connects the Word to the Image of God, according to which human beings were created so that they too, like God, have rationality and a mind, a sort of logos of our own.

But then, due to sin, that image was effaced. Who could restore that image, except the One whom that image reflected? Who could accomplish that, except the Word according to whom human beings were created?

I’ll give you a sampling of what St. Athansius does with these concepts, from the first two chapters alone. From a version available free online, On the Incarnation of the Word – Christian Classics Ethereal Library:

We will begin, then, with the creation of the world and with God its Maker, for the first fact that you must grasp is this: the renewal of creation has been wrought by the Self-same Word Who made it in the beginning. There is thus no inconsistency between creation and salvation for the One Father has employed the same Agent for both works, effecting the salvation of the world through the same Word Who made it in the beginning. . . .

God is good—or rather, of all goodness He is Fountainhead, and it is impossible for one who is good to be mean or grudging about anything. Grudging existence to none therefore, He made all things out of nothing through His own Word, our Lord Jesus Christ and of all these His earthly creatures He reserved especial mercy for the race of men. Upon them, therefore, upon men who, as animals, were essentially impermanent, He bestowed a grace which other creatures lacked—namely the impress of His own Image, a share in the reasonable being of the very Word Himself, so that, reflecting Him and themselves becoming reasonable and expressing the Mind of God even as He does, though in limited degree they might continue for ever in the blessed and only true life of the saints in paradise. But since the will of man could turn either way, God secured this grace that He had given by making it conditional from the first upon two things—namely, a law and a place. He set them in His own paradise, and laid upon them a single prohibition. If they guarded the grace and retained the loveliness of their original innocence, then the life of paradise should be theirs, without sorrow, pain or care, and after it the assurance of immortality in heaven. But if they went astray and became vile, throwing away their birthright of beauty, then they would come under the natural law of death and live no longer in paradise, but, dying outside of it, continue in death and in corruption. . . .

It was unworthy of the goodness of God that creatures made by Him should be brought to nothing through the deceit wrought upon man by the devil; and it was supremely unfitting that the work of God in mankind should disappear, either through their own negligence or through the deceit of evil spirits. As, then, the creatures whom He had created reasonable, like the Word, were in fact perishing, and such noble works were on the road to ruin, what then was God, being Good, to do?. . . .

What—or rather Who was it that was needed for such grace and such recall as we required? Who, save the Word of God Himself, Who also in the beginning had made all things out of nothing? His part it was, and His alone, both to bring again the corruptible to incorruption and to maintain for the Father His consistency of character with all. For He alone, being Word of the Father and above all, was in consequence both able to recreate all, and worthy to suffer on behalf of all and to be an ambassador for all with the Father. . . .

For this purpose, then, the incorporeal and incorruptible and immaterial Word of God entered our world. In one sense, indeed, He was not far from it before, for no part of creation had ever been without Him Who, while ever abiding in union with the Father, yet fills all things that are. But now He entered the world in a new way, stooping to our level in His love and Self-revealing to us. . . .

Thus, taking a body like our own, because all our bodies were liable to the corruption of death, He surrendered His body to death instead of all, and offered it to the Father. This He did out of sheer love for us, so that in His death all might die, and the law of death thereby be abolished because, having fulfilled in His body that for which it was appointed, it was thereafter voided of its power for men. This He did that He might turn again to incorruption men who had turned back to corruption, and make them alive through death by the appropriation of His body and by the grace of His resurrection. Thus He would make death to disappear from them as utterly as straw from fire.

The Word perceived that corruption could not be got rid of otherwise than through death; yet He Himself, as the Word, being immortal and the Father’s Son, was such as could not die. For this reason, therefore, He assumed a body capable of death, in order that it, through belonging to the Word Who is above all, might become in dying a sufficient exchange for all, and, itself remaining incorruptible through His indwelling, might thereafter put an end to corruption for all others as well, by the grace of the resurrection.

[my bolds]

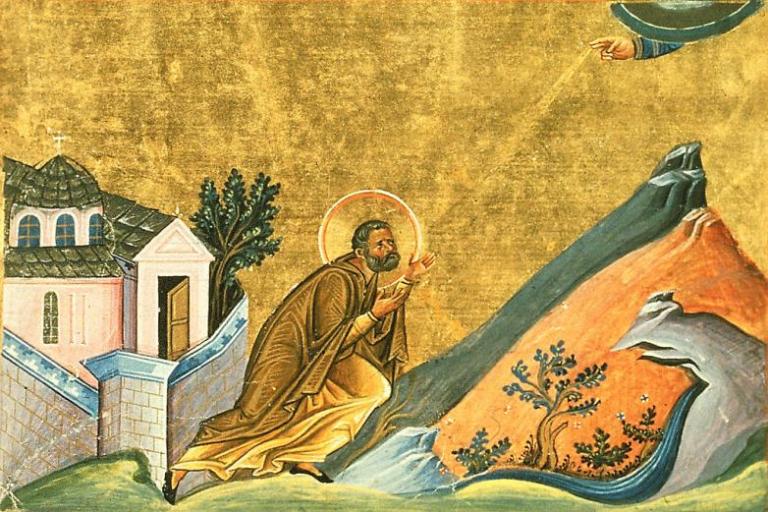

Illustration: Athanasius the Confessor of Constantinople (11th century) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons