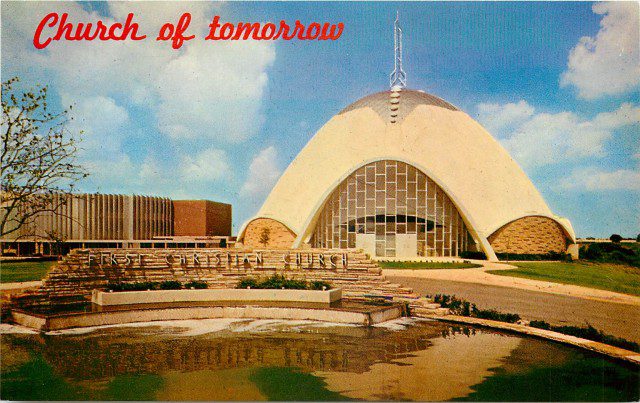

I grew up in the First Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), a mainline liberal Protestant denomination. In its heyday, in the late 1950s, the church body built a futuristic building in Oklahoma City that was known as the “Church of Tomorrow.” I went to lots of conferences there as a teenager, where I was immersed in the modernist theology that everyone there was convinced was going to bring Christianity into the future. Today I read that the building is being sold. And therein hangs a tale. . . .

The Disciples of Christ, being the liberal branch of the Campbellite or Restoration movement that also gave us the First Christians and the Church of Christ, have no creeds. You can believe whatever you want! Surely that’s a formula that can please everybody! What a perfect framework for church growth!

Now under the principle of being able to believe whatever you want, this does leave room for those who believe in Christ, the Gospel, the Bible. My parents. Some of the pastors I remember from my childhood. I actually learned quite a bit about the Bible, thanks to some devout and intense Sunday school teachers from our small town, rural congregation.

But the problem with the official doctrinal position of having no doctrines is, what do you teach? Not theology, or a theological framework for understanding life, the world, or the Bible. Most of the sermons I remember consisted of moralistic principles drawn from Bible stories, but the conservative pastors would add an “altar call” modeled after their evangelical peers.

But having no doctrines was liberating for the seminary professors, the church hierarchy, and the more sophisticated ministers. The Campbellite movement started as an attempt to bring all churches together, so the liberal branch went all in for the ecumenical movement of the 1960s, which operated on the principle of pursuing the unity of churches by minimizing each church’s doctrines. And this openness to all beliefs allowed for the easy rejection of “traditional” Christian teachings and the wholesale, uncritical embrace of the higher critical approach to Scripture, liberal theology, and every variety of modernist religion.

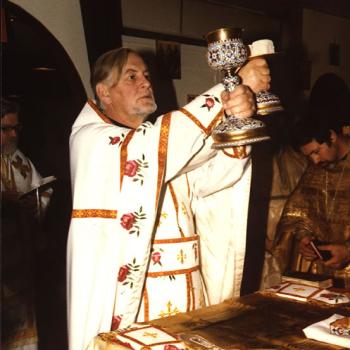

[UPDATE: Certainly it’s possible to have a robust belief in the Bible apart from the historic creeds, as Baptists and conservative Campbellites show. But in the hyper-ecumenical, extremely liberal strain I am describing here, you really could hold to any belief. For example, the Rev. Jim Jones, depicted here, was a minister in the Disciples of Christ. His People’s Temple was held up as a model of urban ministry. After he killed his 918-member congregation with poisoned Kool-Aid, I asked a church official why nothing was done about him. (I belonged to this denomination until I became a Lutheran.) I was told that nothing could have been done, since his mix of liberation theology and encounter group psychology–more toxic than the Kool-Aid–was in accord with our denomination’s principle of theological liberty.]

Thomas Oden, the former liberal theologian who later converted to historic Christianity, tells about the feeling of excitement and optimism of those days, the exhilaration of saving Christianity by remaking it so that it would be relevant to the modern world. As I posted in my review of his book on the subject, Oden was a professor at our Disciples of Christ seminary, Phillips Seminary, in Enid Oklahoma, and he inhabited the same Oklahoma church culture that I did.

All of this was expressed in the “Church of Tomorrow.” Back in the early 1960’s, nearly everyone was obsessed with the future. I yearned to visit Walt Disney’s “Tomorrowland,” which I saw glimpses of on our black-and-white TV. I watched “The Jetsons” (1962-1963) and read science fiction.

I remember being awed by the Church of Tomorrow. It had an escalator! That’s almost like a moving sidewalk! It looked nothing like any other church that I had seen. It consisted of a bulbous dome with a tower that looked like an antenna. It looked like a spaceship! Like a UFO!

The whole structure, inside and out, was rounded. There were no sharp angles. No hard edges. Just like the version of Christianity that was taught there.

In my local congregation I had been taught, though not very specifically, to believe in Jesus and to believe in the Bible. But when I went to state youth meetings, church camp, and youth conferences at Phillips Seminary or the Church of Tomorrow, all of that was knocked down, replaced by the social gospel and the new psychological gospel, with its self actualization techniques and encounter groups. I pretty much hated it, though I didn’t know why, but I kept going because this was the only church that I knew.

When I was in high school, I read C. S. Lewis, who taught me that Christianity actually had content. I was blown away by Lewis’s discussion of the deity of Christ in Mere Christianity. God became a flesh and blood human being? That’s who Jesus is? That’s who God is? Not an abstract philosophical idea or a being far beyond the universe looking down, but the man Jesus? That’s how He could die for us!

I was enormously excited about what I was learning from Lewis, especially about the Incarnation, which I had never heard of before even in my relatively conservative but creedless congregation. I was at a youth conference–actually, come to think of it, I think it was at the Church of Tomorrow–where I started a conversation with a young minister whom I liked and who was leading the youth event. I wanted to talk about the Incarnation. About Jesus. About what that means for us.

I will never forget his answer: “Well, we don’t really talk about that anymore.”

Membership in the Church of Tomorrow dwindled over the years. It once served thousands. Now it doesn’t have enough members to keep it going. The building, as generally happens to cutting-edge works when their time is past, now seems old-fashioned. It was put on the National Registry for Historic Places. It was put on the market for $8.2 million. No one bought it. The price was dropped to $5.65 million. Still no takers. There is talk of a developer considering the 32 acre property for a housing project, which would probably mean tearing the building down.

I thought a megachurch to put in a bid, but the building needs quite a bit of work and it still has an old-fashioned “churchy” feel that would probably put off those trying to come up with a church of tomorrow for today.

Illustration, Historic Postcards via OKC Homesellers