We don’t hear much today about Hell or the prospect of eternal punishment, do we? The popular culture seems fascinated by darkness, horror, and cosmic pessimism, but a realm of everlasting judgment is just too dark to consider. People used to be afraid to sin, lest they incur God’s wrath. But no more, it seems. In the popular religious imagination, everybody goes to Heaven.

This is the teaching of universalism, that everyone in the universe–including the devil–gets saved, one way or the other. St. Louis University theologian Michael McClymond has published two volumes on the subject in a work entitled The Devil’s Redemption: A New History and Interpretation of Christian Universalism.

But doing so much work on the subject has made Prof. McClymond profoundly skeptical of universalism.

My fellow Patheos blogger Scot McKnight at Jesus Creed has interviewed Prof. McClymond. You should read it all. Here is a sample:

McClymond: The sudden rise in support for universalism (see above) seems clearly to have something to do with the church’s current cultural situation in the Western world. What cultural factors are at play? Sociologist James Davison Hunter, I believe, named it as early as the 1980s, when he spoke of the rise of an “ethics of civility” among American younger evangelicals (although this observation might be generalized for evangelicals in Canada, the UK, Continental Europe, Australia, New Zealand, etc.). The all-important principle in the “ethics of civility” is “do not offend others.” Hunter suggested that this attitude was already prevalent among the younger evangelicals of the 1980s—who today would be in their 50s and 60s, and so in key positions of Christian leadership. Many aspects of New Testament teaching were deeply offensive to those who first heard the gospel message (e.g., the notion of a “crucified Savior”). Our twenty-first-century culture may not be offended by the same things, but will almost certainly be offended by some things that are clearly taught in the Bible, centering today perhaps especially on issues of pluralism/exclusivity, sexuality, and eschatology.

Woven throughout the Bible is a message regarding “two ways”—a way of blessing and “a way that leads to death” (Prov. 14:12). A text like Psalm 1 never mentions “hell” as such, but it implies a distinction between the way of the righteous and the way of the wicked, and it suggests a coming time of reckoning, and perhaps also a coming separation. In the New Testament, these themes come much more sharply into focus, for example, in Jesus’ teaching on the sheep and the goats. But let me ask: What will be the likely reaction in a typical American congregation today, if the preacher ascends into the pulpit, reads this passage from Matthew 25, expounds it as literally true, and applies it to the congregation before him? “Some of us here today are ‘goats’ while others are ‘sheep’…..” This will be an offensive message to many people—including church people. Preachers more readily speak about the benefits of being a Christian—“if you follow Christ, your life will be better…” But preachers as well as lay Christians are generally reluctant today to speak about the consequences of deliberately hearing the gospel and rejecting Christ. This may give the inadvertent impression that “everyone is okay” and no one is “lost” or “ruined” in sin—to use more traditional language. This would mean that there is an upside to being a Christian, but no downside to not being a Christian. This may not be what preachers say, but it might be what people hear. The universalist message represents the frosting on the cake—the official declaration that no one is really at risk.

One obvious question is this: On this basis, what does one do with the Jesus of the New Testament, who so often conveyed the idea that many people are indeed at risk (the wheat separated from the tares, the door shut to the feast, etc.)? Consider one gospel text: “And someone said to him, ‘Lord, will those who are saved be few?’ And he said to them, ‘Strive to enter through the narrow door. For many, I tell you, will seek to enter and will not be able’” (Lk. 13:23-24). It seems impossible to reconcile a text like this with universalism. And the longer one spends with the texts, the more uncomfortable one is likely to feel.

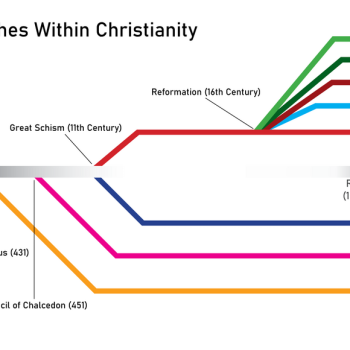

Prof. McClymond says that there are many different theological approaches to universalism. A major strain is from Gnosticism and esoteric Christianity, which teaches that the soul is a spark of the Divine. Thus, at death, the spark joins the whole. As he says, there isn’t really a need for Christ, grace, redemption, or faith.

Some universalists, says Prof. McClymond, believe there is some kind of purgation after death, in which the soul is purified and then allowed into Heaven. Some believe the lost are simply annihilated, not punished eternally, though I’m not sure that is actually universalism. Others believe Heaven is everyone’s destiny, despite their sin or unbelief.

Calvinist universalists can just say that God elects everyone. Arminian universalists can say that everyone will choose Christ, even after death. Lutheran universalists, I suppose, can say that since Christ atoned for the sins of the whole world, the whole world is forgiven (holding to “objective justification” without “subjective justification”).

Liberals, of course, leave out all of the unpleasant teachings of Christianity. But even conservatives, these days, don’t have much to say about “fire and brimstone.” Evangelicals tend to believe in Hell and want to save people from it, but even they draw back from mentioning it.

Could this be one of the reasons for the alleged decline in Christianity? That few people fear God’s judgment anymore? And they think they will go to Heaven–or at worst a peaceful oblivion–no matter what they do, and so feel no need for the divine rescue given in the Gospel?

Or do you think there is still a remnant of that fear of judgment, one that is suppressed in polite company, but which still troubles at least some guilty souls?

Illustration by sciencefreak via Pixabay, CC0, Creative Commons