By Richard Cole

—Continued from yesterday.

On my second day at the abbey, I bounced around, trying to listen, to feel, to be in the moment like Carmen advised. It was a tough slog.

“Waste time. Waste time,” I told myself, checking my watch.

At lunch with the brothers, I casually mentioned that I was in the RCIA (Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults) now. I waited for congratulations but everyone just nodded. One of the brothers asked, “Have you seen the library? You might find that useful.”

After lunch, I found the library. Everything was orderly and well-arranged. I felt calm, the way I do in a workshop, surrounded by tools and lumber. I wandered over to an old Royale typewriter sitting on a small table. On top was a note written in a spidery, elegant hand:

Please do not use or try to adjust any part of this typewriter. It is not only an antique but was used by Abbot Luke Buergler, O.S.B. for much of his work as teacher, priest, prior, retreat master, and abbot. In a real sense, it is a sacred relic. Thank you.

I found a picture album on a back shelf with snapshots from the early days at the lake. It looked like a healthy and vibrant community, with lots of volunteers and neat, well-watered lawns.

Then the pictures stopped. A number of the monks had died in the 1990s, including most of the priests. I’d seen their names at the mausoleum overlooking the lake.

Other things had happened as well, changes in leadership, the gradual effects of old age. The large groups of students stopped showing up. The community needed more money and new members to survive. I thought of a small sign at the gates of the abbey: Fresh Roses. Oh Lord, I thought. How could you support a community selling flowers a hundred miles from nowhere?

After dinner, I went back to the library. At night, with the reading lamps turned on, everything appeared cozier. I found a folder on retreats and looked through the material: how to run a retreat, what retreatants might be expecting, questions to ask. On the back of a schedule, someone had written in pencil:

“He who dares to believe reaches a sphere of created reality in which things, while retaining their habitual texture, seem to be made of a different substance. Everything becomes luminous, animated, loving.”

I thought of the brothers I’d seen that night, eating their macaroni and cheese in silence. Did they live in a luminous world? I found several other notes about the contemplative life, the power of prayer and faith. Then this:

“I can still see only one answer: to keep pressing on, in ever-increasing faith. MAY THE RISEN CHRIST KEEP ME YOUNG! Which means optimistic, active, clear-sighted, and happy.”

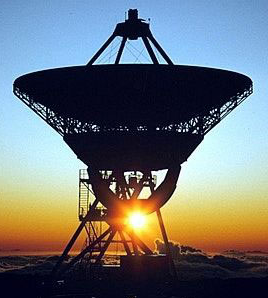

Later that night, brushing my teeth, I thought, “radio astronomy.” That was it. The monks were radio astronomers. Their life was a kind of listening, for themselves and for all of us too puffed up with pride or choked with anger or buried with grief to hear what God was telling us.

I could see the abbey grounds dotted with huge satellite dishes, silently, patiently tracking the heavens prayer by prayer, day by day. Maybe that’s why they were out here, away from all the silly noise and blare. This abbey was their observatory, and on this isolated bluff, the monks could better hear those faint signals from the other side of the galaxies inside our hearts.

“Don’t analyze,” Carmen said when we met on Sunday after Mass. “Think about what’s happened to you this weekend, but don’t analyze it. You don’t evaluate a loving relationship. You’re simply there with the beloved.”

I closed my notebook. She added, “One more thing: God wants to you be happy. Jesus, or saints like St. John of the Cross, they all knew pain, a great deal, and yet they wanted us to be happy. I’m not talking about being what you might call pathologically nice. Simply accept the happiness that God gives us.”

“Ah.” I couldn’t think of anything else to say, so I didn’t.

She continued. “The true leaders in this world aren’t the politicians or rulers or millionaires. They’re the people who are truly happy. We all naturally gravitate to these people. We try to shape our lives around what they represent because we realize that what they have is more powerful than anything. So be happy. Life should be something like a festival.”

We said goodbye, and she gave me a big hug. “Think of the abbey as your home away from home,” she said, and as I went out the door, she called out, “Remember, God is crazy about you!”

Two years later, I learned that the monastery was shutting down. That came as a jolt. I had notions that monasteries endured for hundreds of years, that somehow they didn’t have to worry about money. Rome would provide.

But in fact, each monastic community has to be self-supporting, and the abbey had been losing money for years. The Benedictine leadership looked at the situation and decided, reluctantly, that the abbey had to close. The monks dispersed, some to monasteries in North Dakota, Oregon, and Arkansas, others to nursing homes.

But the day I left, I only knew that I’d been blessed by being in their presence. When I gave the porter a check on the way out, he wished me a safe trip, and I wanted to say something about the community and radio astronomy and listening.

But I didn’t. If someone gives you a gift, you say thank you, so that’s what I did. I told him that the community had helped me enormously, that the monks were doing important work.

He looked touched, this elderly monk, and his kind, gray eyes looked even kinder for a moment. “Thanks,” he said. “We don’t often hear that.”

Richard Cole is the author of two books of poetry: The Glass Children and Success Stories. He has recently completed a memoir: I Have Wonderful News: A Catholic Conversion, from which this blog is adapted.