Today I want to take up the question that ended yesterday’s post: Is Superman the Übermensch?

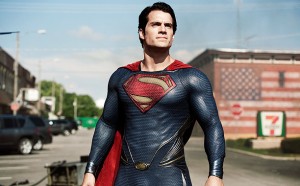

As a host of commentators have pointed out, Superman’s conventional morals have never positioned him as the destroyer of societal norms that Nietzsche championed. In Man of Steel, our hero’s forbearance toward his human antagonists make it clear he isn’t about to super-speed beyond good and evil anytime soon. Yet all the loving compassion in Henry Cavill’s baby blues can’t erase the fact that humanity doesn’t want a mangy drifter for a Messiah, or even a clean-scrubbed-but-nondescript farm boy: it wants a demigod.

It’s telling that, in this revision of comic book history, the “S” on his chest actually represents the Kryptonian symbol for hope. Misinterpreting this, the humans dub him Superman. What’s a self-effacing savior to do?

Indeed, the cosmos itself seems hell-bent on forging Kal-El into Nietzsche’s prototype. The collision between Kryptonian biology and Earth’s atmosphere produces Clark’s horrifically heightened sense of perception, such that his childhood memories involve seeing his teacher as a walking skeleton. In his all-encompassing sensorial receptivity, Clark recalls the Overman’s capacity to absorb life’s totality, incorporating Dionysian chaos and Apollonian order into his being without missing a (goose)step.

As for the Overman’s embrace of eternal recurrence—all possible events that have and will occur—Clark’s identification with the past-as-future is imprinted within his being. Before launching his superboy into space, Jor-El encoded into his son’s DNA the genetic information necessary to resurrect his race. Clark carries in his very marrow the seeds of Krypton’s stratified society.

Nietzsche, of course, looked to eternal recurrence to safeguard against the Christian preoccupation with future judgment: “Not to look to distant unknown salvations and blessings and pardons, but so to live that we would want to live again and want in eternity thus to live!” But this Superman supersedes Nietzsche’s binary. For humans, he represents a “distant unknown salvation,” yet for Kryptonians, he represents the possibility that Krypton, for all its sins, can and should live again.

Superman, in short, embodies the American drive to have it both ways, to embrace the best of the Overman and the best of the slave morality Nietzsche despised. Superman’s omnipotence, combined with his capacity to revive his race, means he can act as Christlike bridge between Kryptonian lion and Earthling lamb.

If refuting Plato’s social stratification recapitulates America’s origin myth, then this merging of Son of Man and Overman surely sketches the terms of manifest destiny that fueled its expansion.

Throughout the film, this uneasy détente between Christian and Nietzschean ethics is threatened by the temptation to ditch the meek-and-mild act. As Kryptonian vixen Faora observes before engaging Superman in battle, “The fact that you possess a sense of morality and we do not gives us an evolutionary advantage.” (Although apparently not an elocutionary one: wasn’t there a pithier way for Faora to slip in her ode to Social Darwinism?)

Superman’s Nazarean dreams in a Nietzschean cosmos are cast into sharp relief by his existential photonegative, General Zod. After Superman foils Zod’s plot to terraform Earth into a new Krypton, the general expresses a transcendent drive for revenge. “I was bred to serve my people…. Now I have no people. My soul…that is what you have taken from me!” If that’s not a line from The Genealogy of Morals by Zod, it should be.

This final showdown culminates in the Neck-snap Heard Round the World. Faced with a choice between saving a family and putting down the last surviving co-heir of Krypton, Kal-El opts for the latter. Superman’s choice to kill has provoked fans to righteous fury. Yet this apparently heretical departure epitomizes the spiritual ambivalence in which this Superman finds himself enmeshed.

As much as Superman might desire a third option, his decisive action is precisely what proves that, for all his superpowers, his allegiance lies exclusively with his adopted people. Here, then, is the ultimate sign that Superman has absorbed Pa Kent’s ambivalent advice: sometimes you protect life, sometimes you end it, and sometimes you accomplish both in one fell swoop.

This ad hoc code of ethics is, in the end, the only way for the Last Son of Krypton to satisfy the existential demands the universe has placed upon his shoulders. Interestingly, the Superman-Zod match immediately follows the sacrificial death of sidekick Colonel Hardy. The juxtaposition between Colonel Hardy’s noble demise and Superman’s morally ambiguous death-grip is too pointed to chalk up to mere screenwriting excess: sacrificial death is one bridge too far for this Messiah, particularly given the predestined appearance of Man of Steel 2.

Crucifixion will have to wait till the third film, if not the next reboot.

Indeed, Man of Steel offers an incisive if inadvertent meta-commentary on what we want from our alien superhero. Give us just enough Christ to offer the hope of salvation, and just enough Overman to deliver it without ending the franchise. Give us a hero who embraces the will to power, the drive to self-create and differentiate from the herd—but make sure he loves his mother, too.

Give us a hero whose self-imposed sensorial limitation reflects our self-imposed moral selectivity, our choice to gawk at 9/11 disaster porn one minute and, moments later, tremble for the fate of the one family who seems to have survived the holocaust. Above all, give us a hero who’s kind of hot (but no spit-curl, please, this is the 21st century).

In the end, the Man of Steel may take up journalism not merely as alibi but as escape from the fussy requirements of his vocation: at least at the office, he has nothing more pressing to worry about than keeping his eyeglasses on. And let’s be honest–given the choice between a desk job and saving the world on such specific terms, wouldn’t we feel the same way?

Lucas Kwong is a doctoral candidate in English Literature at Columbia University, specializing in religion and late Victorian literature. When he isn’t writing about Dracula or obsessing over the ideological underpinnings of summer movies, he’s writing music and performing as part of garage rock act Brother K (brotherkmusic.com).