I found respite recently in Jeanne Murray Walker’s essay on Alice Munro in Image, describing Munro’s domestic fiction, and related utterly to Walker’s wrestling with “Doing Something Important.” It is a place I find myself often, wondering if the few hours a week I have of child care for the baby are an example of my missing what I am supposed to be living and learning. Jesus does not say to come to him as someone Doing Something Important, but as a little child.

I found respite recently in Jeanne Murray Walker’s essay on Alice Munro in Image, describing Munro’s domestic fiction, and related utterly to Walker’s wrestling with “Doing Something Important.” It is a place I find myself often, wondering if the few hours a week I have of child care for the baby are an example of my missing what I am supposed to be living and learning. Jesus does not say to come to him as someone Doing Something Important, but as a little child.

You’re not supposed to write about your own children if you want to be a real writer. Too cliché, too sentimental. But what about the one whose birth we so recently celebrated? This isn’t sentimental—it’s the real deal. A child is born in Bethlehem, and he is the king of kings. This is earth shattering. There’s something there we’re meant to learn. Maybe even everything.

A December 2004 article in Time notes that the nativity story is the part of the Jesus history that gives scholars most trouble. Only Matthew and Luke talk about the birth of Jesus, and like most parallel accounts in the Bible, their stories contradict each other. Neither account is given much room on the page for a holiday of such current social and commercial import.

The Time article combs through current Biblical scholarship to deconstruct the Nativity. The richly layered story bows to traditions of the past (virgin births), diversity (Magi), and centers this world change on the poor (the manger). It seems likely that Jesus was born in Nazareth and not in Bethlehem. In a Christian anthropology class (taught by a Jesuit), the professor explained the use of the word “virgin” as specifying Mary as a young woman, mother to Jesus, a man of flesh and blood and not spirit as some were wont to think in the second century.

This might shake a few people up a bit; it doesn’t bother me in the least. Deconstruction never worked as a way to dismantle meaning. Both explication and defending historicity miss the point entirely, when, like most things, the whole is more of the sum of its parts. Ross Douthat’s Ideas From a Manger published on the winter solstice suggests what we need to know about the nativity story in whole: “an entire worldview in a compact narrative…the vertical link between God and man (and)…the horizontal relationships of society…(locating) transcendence in the ordinary.”

Both of my sons were born within days of Christmas. One thing that I understood at their births with a fierceness at once primal and divine is best articulated by a rabbi who conducted a friend’s b’rit milah, or baby naming. This rabbi explained that Jewish tradition is for all to rise when a pregnant woman enters the room: she may be carrying the Messiah. There is the possibility of divinity in every unborn child, and it follows there must be then the possibility of divinity in every mother.

There are times when my baby wakes up when I’m in the middle of writing; he’s up early. I’d planned on him sleeping another hour. I might change and feed him, smile and cluck, let him crawl around a little, but there are times (many, even) when my thoughts are divided between wonder and what’s next on the page.

I heard Sherman Alexie once discussing writing and books. I remember only his secret to parenting two boys. “It’s a pretty simple equation,” he said. “You have to get down on the floor.” I know there must be a balance between work and kids. But I’m terrified that the real wisdom is not in what I’m turning over in my mind, my attempts to articulate the wonder I feel, or the distress, the meaning of it all. The real wisdom is in that child exploring the living room, pulling the ornament off the tree, tasting his sock. Real wisdom is in spending time with him, turning over to him my heart and my mind. No matter what and how much I’ve studied, what I need to know is in his smile.

There are times in the morass of laundry and dishes that I look at my children and for a moment my noticing arrests the mercurial speed with which they are growing, snatches for a moment the sheer beauty of it all. There is urgency in teaching them what they need to know of God and the world.

My eldest and I recite the Lord’s Prayer and Psalm 23. I read him stories from a children’s Bible. I watch him watch me when I teach Godly Play at Sunday School, running my fingers through the sand, talking about the desert. I look at my children again, and what I know knocks the breath out of me: the real urgency is in what I must learn from them.

“To love another person is to see the face of God,” wrote the great Victor Hugo. All we need to know of humanity, its triumphs and its limits, we know through parenting; all we need to know of God we know through a child.

When my sons came into the world, I remember the hard pressure, the first cry, watching and holding a new person and an old soul (“We are not bodies that have souls,” Lewis reminds us. “We are souls that have bodies.”), the shattering of beauty and fatigue. That hour with the angels at birth and death, at the manger and the cross, is subsumed quickly by exhaustion and a child’s endless needs, but the glimpse—it is sun spattering off rime ice on crisp winter branches. This amazement still erupts when I least expect it: the baby squeals and grins, my four-year-old holds up wolf lichen again (and again) and exclaims each time: Mama, a treasure!

I am starting to understand that each woman is Mary, and each child is the Christ: divinity knit into our souls and flesh, Christ among us, Christ within us. Everything we need to know is about a baby. The minutes of daily life wear down that vision at times—most times even. Pursuit of the Important does not help me understand it more. That is the lesson of Christmas, the meaning of the Christmas story.

Shannon Huffman Polson is the author of North of Hope: A Daughter’s Arctic Journey. Her essays and articles have appeared in a number of literary and commercial magazines including Huffington Post, High Country News, Adventum, Cirque Journal and Alaska and Seattle Magazines. She can be found writing or with her her family in Seattle or Alaska, and always at her website, Facebook, and Twitter.

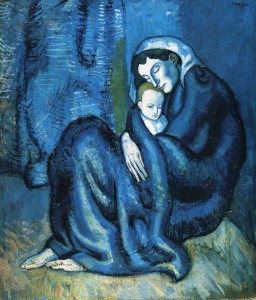

Image used: Pablo Picasso. Mother and Child, 1902. Oil on canvas. 112.3 x 97.5 cm. Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge.

You can make your tax-deductible gift to the Image “Making It New” campaign here.