My hematologist, who has monitored my leukemia for the past ten years, copied me into an email he sent to his colleagues. It was the poem “Beannacht” by Irish poet John O’Donohue, which begins:

My hematologist, who has monitored my leukemia for the past ten years, copied me into an email he sent to his colleagues. It was the poem “Beannacht” by Irish poet John O’Donohue, which begins:

On the day when

The weight deadens

On your shoulders

And you stumble,

May the clay dance

To balance you.

And when your eyes

Freeze behind

The gray window

And the ghost of loss

Gets in to you,

May a flock of colors,

Indigo, red, green

And azure blue,

Come to awaken in you

A meadow of delight.

What a grace to have a doctor who would send this around to his colleagues. This is what I want in all my doctors: human beings in touch with the full range of human emotions. People who respond to poetry.

My primary care doctor has similar sensibilities. Her special interest is in teaching doctors how to listen to their patients. She’s a knitter, hence someone in touch with her own creativity. She has long volunteered with hospice, so she’s attuned to the complex needs of dying people and their families.

My optometrist always asks about my current knitting project before she puts those stinging drops in my eyes to begin her examination.

The day after my husband went to the hospital for an angiogram and was found to need immediate quadruple by-pass surgery, his cardiologist phoned me to apologize: “I’m sorry I didn’t catch this sooner,” he humbly said.

When I was hospitalized with pneumonia last summer, the doctor on rounds would come in each morning to check on my condition. After he’d finished examining me, he and my husband would chat about books they were reading. I loved that; it was as healing as whatever meds he was giving me.

I’ve known since childhood that physicians are people. My father was one, and his colleagues were often at the house for social occasions. But, as I’m sure you’ve experienced, many physicians think that they’re not supposed to act like full human beings in their doctor-patient relationships. Or they’re afraid to show emotion, considering this unprofessional.

But—and what a gift of a “but” it is—to counterbalance this attitude, we have Rafael Campo: poet, physician, Harvard Medical School professor, essayist. At Harvard he teaches about art and medicine, describing the program with these words:

The difficulties of practicing medicine in a modern era increasingly dominated by economic constraints, technological hubris, and multicultural differences have been well described. Yet little constructive work has been done to refocus the attention of care providers on the universal nature of human suffering itself, and how empathy can continue to be modeled for aspiring care providers, especially medical students, under these changing and sometimes hostile conditions. The growing body of art and literature that responds to the illness experience is a powerful but underutilized medium for pondering and valuing the work of physicians, and for nurturing their personal growth and their dedication to what was once termed “the healing art.”

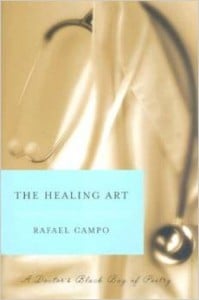

The Healing Art. Campo has in fact written a book with this title, in which he talks about how he gives his patients poems as well as prescriptions. He chooses poems by contemporary poets: poems about their own illnesses, because “poetry locates us inside the experience of illness, demanding that we consider it from within as attentively as we do from without.”

For each patient, he chooses a poem that offers metaphors for the patient’s particular illness. “Creating metaphors,” he writes, “is itself in fact a process similar to the healing process, involving an imaginative translocation from one state or position to the other.” Furthermore a poem, “in its rhythms and rhymes, metaphorically might restore the sufferer’s sense of control over deranged bodily functions.” Campo invites his patient to meditate with the poem he has “prescribed”—and also to write some lines in response to or in conversation with the poem.

In his own poetry, Campo sometimes writes about what it’s like, deep down, to be a doctor. One of my favorites about the doctor-patient relationship is called “What I Would Give” (from his collection Landscape with Human Figure):

What I would like to give them for a change

is not the usual prescription with

its hubris of the power to restore,

to cure; what I would like to give them, ill

from not enough of laying in the sun

not caring what the onlookers might think

while feeding some banana to their dogs—

what I would like to offer them is this,

not reassurance that their lungs sound fine,

or that the mole they’ve noticed change is not

a melanoma, but instead of fear

transfigured by some doctorly advice

I’d like to give them my astonishment

at sudden rainfall like the whole world weeping,

and how ridiculously gently it

slicked down my hair.

I’m blessed to have some doctors who are comfortable with giving me their “astonishment / at sudden rainfall.” But I want everyone to share in this blessing. If only all physicians gave what Campo offers.

Peggy Rosenthal is director of Poetry Retreats and writes widely on poetry as a spiritual resource. Her books include Praying through Poetry: Hope for Violent Times (Franciscan Media), and The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford). See Amazon for full list. She also teaches an online course, “Poetry as a Spiritual Practice,” through Image’s Glen Online program.