In my last post on education, I took exception to the platitudinous character of so much of official Church discourse, in particular on education. I got some pushback on this, from Sam in his latest post and on Twitter.

Because Sam and I now largely understand each other on education, I want to jump off on this and take a stand on something that I think is important.

In my post, I described platitudes as reliable, obvious predictions of the future, as opposed to the reliable, non-obvious predictions of the future that science makes. To summarize and broaden, I think we can pretty well define a platitude as something that is (a) true and (b) which everyone takes for granted.

Christians should eschew platitudes.

I am fairly sure that the least platitudinous person to ever walk the Earth was the man Yeshua of Nazareth. I am fairly sure that the least platitudinous text in the history of text is the Beatitudes. It’s almost like the only thing God can’t do is be boring.

It’s impossible for the Beatitudes to be platitudinous. Even if you know them by heart, even (especially) if you live them, they always shock you anew. If it shocks you, it’s not a platitude. You may “know it in theory” but if you meditate on them you are still shocked, still jostled, still made uncomfortable.

Probably the least platitudinous text outside the Bible is the Nicene Creed. Almost every word is a slap to the face. I believe. Wait, you mean faith is an individual adhesion and not an imposition by membership in a social group? In one God. Wait? One God? Father Almighty. Wait, this God is Father, he is not just an unmoved mover, he loves and protects and sustains his family?

And that’s before we even get to that stuff about the Trinity and the Incarnation.

That shit is never platitudinous, bro.

Here is a relevant quote from Met. Kallistos Ware:

True faith is a constant dialogue with doubt, for God is incomparably greater than all our preconceptions about Him; our mental concepts are idols that need to be shattered. So as to be fully alive, our faith needs continually to die.

Here Ware is mainly addressing the very Modern preoccupation with reconciling faith and doubt, but the point is that the truths of faith are never platitudinous. If they are obvious, self-evident, then you have created an idol that needs to be shattered.

Now, think of the role of the Church in any society–as a sign of contradiction. There is a Venn diagram. By God’s common grace, every society and culture will hold some beliefs in conformity with the Gospel of Jesus Christ; because of original sin, every society and culture will hold some beliefs opposite to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Stuff that is inside the overlap is platitude; stuff that is outside the overlap is beatitude. The Church’s job as evangelist is to work as hard as possible to increase the overlap between the two circles; to pull the society’s circle into the Church’s circle. To do that, you have to get people to step out of their comfort zone. You have to be “folly to the Gentiles and a scandal to the Jews.” You have to be a sign of contradiction. You have to live to get radical.

Because the Church is a good evangelist, sometimes verities of the Church become translated by societies into platitudes–but never at their full, never with their radicality. By definition, social order doesn’t do radical; by definition, the Church does, or ought to.

And platitudes move around. A platitude is something that is obvious to everyone, and what is “obvious” to everyone changes. “A child in the womb is still a child” used to be a platitude–no longer. But, at the time when it was a platitude, “single mothers have equal dignity in Christ” was not a platitude, and I’m thinking we should have said that more. “Marriage is impossible without the consent of the spouses” is a platitude; for most of human history it was not, and it is thanks to the Church that it is now a platitude. Is it really the most important thing the Church has to say about marriage today? Only recently did “gay people have equal dignity” become a platitude; and because when it was not a platitude the Church did not say it, the Church now has no credibility when it tries to say non-platitudinous stuff about homosexuality.

Let me take another example: “everyone has a moral duty to take care of those less fortunate than themselves.” Today, this is a platitude. It was never a platitude until the Church came along. It is striking and funny and ironic to see secularists proclaim that they don’t “need” Christianity to have a duty towards those less-fortunate even though this is a deeply Christian idea. But it is now a platitude. Surgeon General’s Warning: watching a bishop say we need to care for the poor causes narcolepsy. The general idea that “care for the poor is good” is firmly at the middle of the Venn diagram.

What Pope Francis says about care for the poor, however, is anything but platitudinous. Instead of merely outsourcing our duty to the poor to the government or “the Church” (understood as a bureaucracy we are apart from) we should always go at the peripheries and the margins of human existence. To help the poor is not to give someone a check, it is to have a personal relationship with them so that they are treated as full human beings and you learn from them. This is not platitudinous. It is radical.

At any given point in time, the texts of the Magisterium will provide a very big arsenal for someone who wants to go through life saying and believing nothing but platitudes. But this is not the life Christ calls on us to lead.

I think this is important because I think the Church has a big problem. I think the Sexual Revolution and its various consequences have created a confusion in the minds of many people who believe themselves to be “traditional” Christians, which is to associate the sexual morality of the pre-Sexual Revolution era with the sexual morality of the Gospel; consequently to see anything that has happened between, say, 1968, as consisting only of decline and apostasy, and to look at the pre-1968 world through rose-colored glasses; consequently to believe that the mission of the Church is to return the world to this Golden Age.

It shouldn’t need saying that this point of view is, from the standpoint of Catholic Tradition, erroneous and even idolatrous. First of all because, for the reasons I have explained, there is no Golden Age. Second of all because the sexual morality of any given society or era is going to come drastically short of the Gospel. If you doubt me, read the Magisterium of John Paul II, who clearly embraced the good of what came post-1968.

This is an absolutely key thing, because fidelity to “prelapsarian” sexual morality is not fidelity to the Gospel. It is fidelity to an idol. It is the lack of this distinction which hobbles so much of the Church’s commentary on current events, and which leads the Church to lack credibility in the public square. And for people who hold these views, sexual morality is, indeed, summed up by a bunch of platitudes.

It was because I sensed a lack of this crucial distinction that I did not support France’s campaign against same-sex marriage. And indeed, after the unexpectedly successful campaign, a political movement to support the protest’s ideals was founded. Its name? “Common Sense.”

Common sense, like platitudes, can be good, it can be bad. But it is never the Gospel.

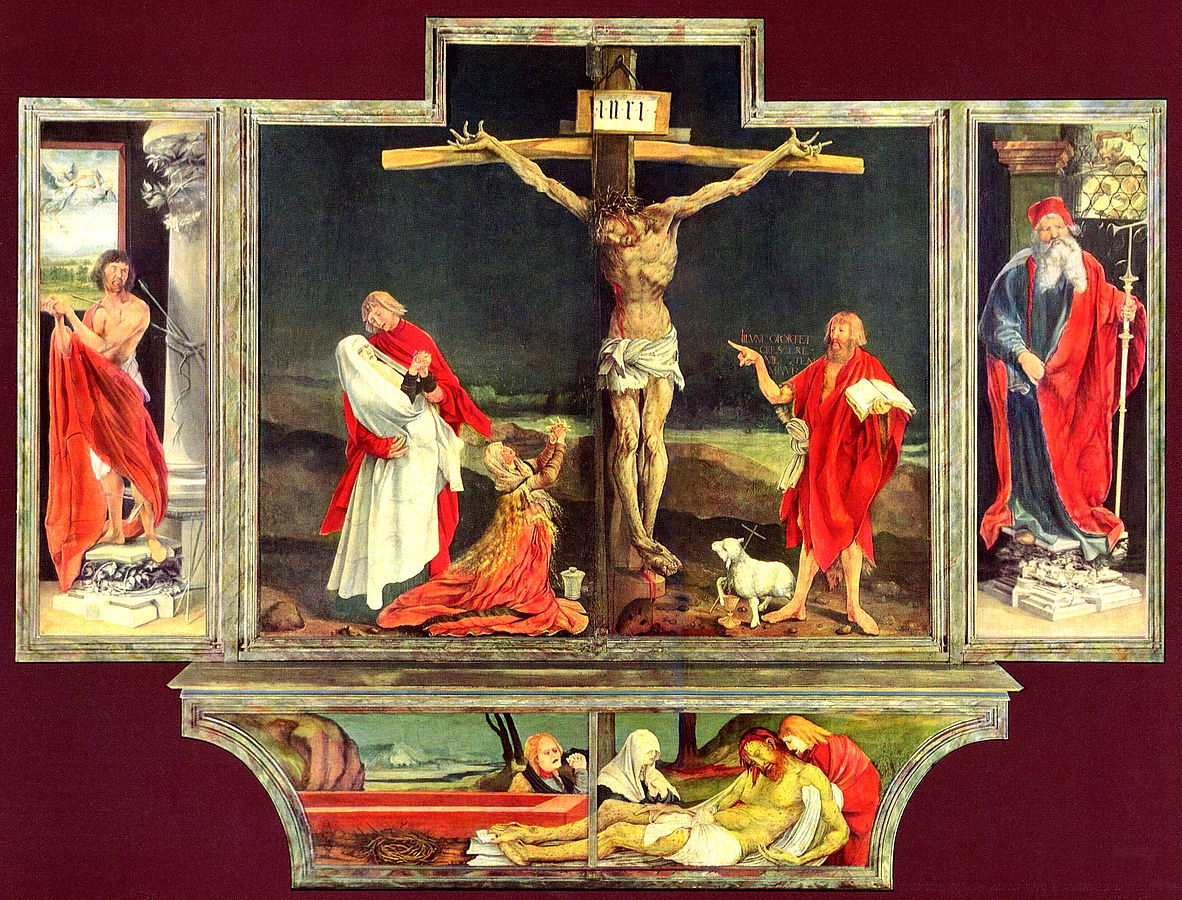

The Issenheim Altarpiece, pictured above, was so striking at the time, and even today, because it does not artistically gloss over the brokenness and utter dependence of the crucified Christ. God, the maker of Heaven and Earth, all things visible and invisible, the Lord of Hosts, really became a man, a theantropos, and loved his creatures so much that he followed this love unto the Cross of a slave, unto destitution, suffering and death. This reality can never be a platitude. It always challenges us. The Issenheim Altarpiece reminds us that the Cross is not just a nice concept, but the absolute brokenness of a man humiliated, “despised and rejected of men”, and that this man is also God. Nothing that is seen from the vantage point of the Cross is ever platitudinous.

If it is a platitude, it is not the Gospel.