These thoughts are a continuation of Nathan Rinne’s post Playing the Pietist Card.

It is extremely common in Lutheran circles to hear the refrain: “You’re a pietist,” or “that’s pietism.” The term is used so often that it virtually has no meaning any longer, and it is used synonymously with legalism, or salvation by works. The problem here is that pietism is an actual historical movement with its own particular theological roots, practices and beliefs. In a day of theological soundbites and 140 character debates, such terms are utilized devoid of their actual historical context. Pietism seems to be used in the same manner as hyper-Calvinism, as a term of attack without any consistent definition. Just as hyper Calvinism does not mean “someone who is really into Calvinism,” so pietism does not mean “someone who is really into sanctification.”

So what is pietism? Pietism was a movement within Lutheranism, beginning with Philipp Jakob Spener (1635-1705) who saw a decline in practical piety in the Lutheran church. What Spener encountered, according to his own account, was a theological orthodoxy that had no spiritual life. People viewed the church in a ritualistic manner with no living faith, and preachers often used the pulpit for academic lectures rather than proclamation of the law and gospel. It was in this context that Spener wrote his famous Pia Desideria, encouraging personal piety and Bible study. Spener himself held firmly to Lutheran orthodox theology, never abandoning the orthodox doctrines of the sacraments, justification, and the distinction between Law and Gospel. The stalwart of orthodoxy, Abraham Calov, actually supported Spener’s work at first, recognizing that he was addressing real problems in the German church, though rejected Spener’s work after seeing some of the sectarian effects of his reform.

In contemporary discourse, pietism is often dismissed as a legalistic works-righteous movement within the Lutheran church. However, this is an extremely simplistic evaluation of a complex historical movement. Pietism was not one coherent movement, with one set of distinctive beliefs. Some pietists held firmly onto Lutheran Orthodoxy, while others, known as the “radical pietists” echoed many of the errors of the Anabaptist movement. Pietism should be seen more as a spectrum, with both positive and negative influences in the church. Whether we want to admit it or not, nearly all of us have been influenced in some ways by pietism.

There were several positive effects of the pietist movement. Most notably, the pietists helped start the modern missionary movement, emphasizing the need for personal evangelism and outreach. God used pietism to bring Christianity to several nations who were previously without the gospel. Pietism also helped to emphasize the importance of personal Bible study. The use of study Bibles and other materials by laity, commonplace in the church today, is largely due to Spener’s reform. Pietist theologians authored several helpful exegetical works, bringing an emphasis back to Scripture, whereas it had previously been on systematic theology. The practice of Sunday school was also instituted through pietism, and any Lutheran congregation that has a Sunday school program should acknowledge their debt to pietist leaders. Finally, it was pietism that guarded many Christians against the ideas of the enlightenment, holding firmly to the truthfulness of God’s inspired Word, and the historical veracity of its contents.

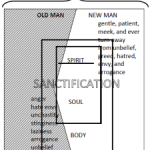

Along with these positive elements of pietism, it had a negative impact upon the church in other ways. Pietism tended toward an individualistic spirituality, and thus downplayed the importance of the visible church. The emphasis on personal conversion sometimes negated the central teaching of regenerative baptism and the real presence of Christ in the Sacrament of the Altar. The emphasis on exegetical theology unfortunately negated the important theological distinctions developed in the scholastic era. Pietist preachers also tended to confuse law and gospel, sometimes waiting to proclaim the gospel until there were enough “signs” of one’s repentance. Perhaps most importantly from a Lutheran perspective, many pietists emphasized the reality of sanctification over that of justification, and thus de-emphasized the objectivity of the gospel. In it’s worst forms, pietism abandoned historic Lutheran teaching altogether, adopting a sectarian attitude and a rigorous legalism.

Like any historical movement, pietism had several positive and negative elements. To use the term in a purely derogatory manner is simply not historically accurate and ultimately unhelpful for productive theological discourse. We should cease calling people who we think emphasize sanctification too much “pietists,” unless they themselves are actually within the historical tradition of pietism, being theologically influenced by Spener, Francke, etc. It is also important to remember that several beloved Lutheran theologians have sometimes been considered pietists such as: Bo Giertz, C.F.W. Walther, David Hollaz, and Adolf Koberle.

I contend that we should simply stop using the term “pietist” in theological debate unless one actually claims to be a follower of historic pietist teaching, or is part of a historically pietist church body such as the AFLC or the CLB. To do otherwise is historically dubious, and unproductive in theological dialogue.