Apologies for my hiatus; I had a few very hectic weeks with other projects. On to the lectionary!

Joel 2:23-32 and/or Sirach 35:12-17 and/or Jeremiah 14:7-10, 19-22

What It’s About: The Joel and Jeremiah texts are classic prophetic texts of hopefulness in God’s faithfulness. The Joel passage is most well known from its citation in Acts 2 (the Pentecost story), and the Jeremiah text is probably less well known, but it has a similar theme. The Sirach text, meanwhile, is about God’s provision for the poor and powerless of various kinds.

What It’s Really About: The witness of the prophetic books is pretty overwhelming on a few fronts. The prophets condemn selfishness and immorality. The prophets advocate justice. And the prophets are relentlessly hopeful about the future, despite the gloom of the present moment. This is not a bad place to start from in this season of life in the United States, as the election season (and especially the presidential race) is having intense emotional effects on people. No matter which candidates you think would be better, there seems to be unanimity among Americans that something has gone off the rails in our national life, and the prophets couldn’t agree more. The prophets usually arose and spoke in times of crisis, and they both diagnosed what was wrong with the society and suggested that despite appearances, God had not forsaken the people.

What It’s Not About: Sirach 35:14 is fascinating: “Do not offer him [God] a bribe, for he will not accept it; and do not rely on a dishonest sacrifice…” This kind of bargaining with God is familiar to many of us; we try to bribe God with promises of change and better living. But Sirach goes on to say that “with him there is no partiality,” which means that God sees through our pleadings to who we really are. Better to be honest in the first place.

Maybe You Should Think About: It’s interesting that both the Joel and the Jeremiah passages mention environmental degradation and trauma in the context of social unraveling. The Joel passage is set in the aftermath of a locust infestation, one of the scariest things that could happen for a subsistence farmer in a pre-industrial society. And the Jeremiah passage makes reference to God’s role in bringing rain, and how the gods of other nations cannot help to break a drought. Ancient people were more connected to the cycles of nature than we are; we don’t usually think about the systems that sustain us unless they completely fail. But ancient people understood that their lives hung in the balance of rain and plagues of insects and sun and earth. Our lives do too–we just don’t think about it as much.

What It’s About: This is an interesting passage, because it conveys biographical information about Paul, but almost all scholars agree that Paul did not write 2 Timothy (or the other Pastoral Epistles, either). So in all likelihood, what we are seeing here is a tradition about Paul, not his first-person account of things. Already by the time this letter was written, perhaps in the early years of the second century and perhaps a half-century after Paul’s death, there was a tradition of Paul’s imprisonment and suffering. The book of Acts narrates Paul’s life right up until the moment where this letter seems to take up the story: Paul was imprisoned (under house arrest) in Rome, awaiting an audience with the emperor. We don’t know for sure what happened to Paul, but there are traditions that he was martyred in Rome, and the fact that we never hear from again probably points that direction too. This passage, and all of 2 Timothy, imagines what Paul would say from that imprisonment.

What It’s Really About: Verse 6, where the writer says that “I am already being poured out as a libation, and the time of my departure has come,” is very interesting. It’s a clear reference to his death, but it’s cast as a libation–a ritual offering to God (or the gods) in the form of pouring out a drink. This is sacrificial language, not unlike the way the gospel of John emphasizes that Jesus is the lamb of God, like the lambs slaughtered at the passover. The early church celebrated with libations, although it isn’t a part of the tradition that remained particularly strong. It’s also interesting that in verse 17 we see that already by the early second century Paul’s mission was understood clearly as having been to the Gentiles. There is much controversy in biblical scholarship today about the nature of Paul’s mission…was he an apostle to Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome, or was he an apostle specifically to the Gentiles in those places? The book of Acts (which, as the notes in my Harper Collins study bible tell me, the writer of 2 Timothy probably knew) always has Paul go first to the synagogue wherever he went, but Paul’s own letters tell a story of a much more Gentile-intentional mission. The writer of 2 Timothy seems to agree with Paul more than Acts, and sees Paul as a particularly Gentile apostle.

What It’s Not About: This passage skips verses 9-15, which is a shame. This kind of material, where the writer is giving shout-outs to individuals, is among the most interesting and valuable in the New Testament. Romans 16, for example, is a treasure trove of information about Roman Christianity. Here, though, the material is still more fascinating, because, remember, the author isn’t Paul. This is someone, 40 or 50 years after Paul had died, mimicking Paul’s style, and trying to come up with the kind of shout-outs that it might have been plausible for Paul to make! That’s remarkable! Maybe Alexander the coppersmith (verse 14) was the stuff of legend for what happened to him, so it made sense to include him. Maybe Tychichus (verse 12) was known to the audience in recent memory as a figure in Ephesus. It’s fascinating to think about why these particular verses were included.

Maybe You Should Think About: This letter belongs to a particular sub-genre of literature, in which the thoughts of a dying or soon-to-die person are written by another person, imagining what they might have been thinking. These often take the form of instructions or moral exhortation to those who survive, and that is exactly what 16-18 do. Both this section and the earlier verses in 6-8 are meant to be understood as encouragement for people under persecution of some kind or another, that they could draw strength from Paul’s trials.

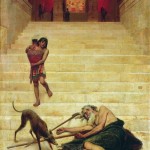

What It’s About: This is a short but potent parable about humility before God. It’s the story of two men, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. Everyone would have expected the Pharisee to be the righteous one and the tax collector the bad one, but in their attitudes before God, they prove that the opposite is true. Jesus here is inverting the usual understanding of the rankings of righteousness.

What It’s Really About: This is connected to that passage from Sirach above, in which God cannot be bribed. These two men both approached God for prayer, but one did so in full honesty about who he was (“the tax collector, standing far off, would not even look up to heaven, but was beating his breast…”) while the other assumed that he was more holy than he really was…especially in comparison to the tax collector. The one who is being honest is the one best received by God, and the one who was lying to God about his own character went home unjustified.

What It’s Not About: Pharisees are a favorite target of gospel-writers and modern Christians; we have made their name into a synonym for “hypocrite.” But it’s worth pointing out that this whole parable depends on the audience understanding that a Pharisee would have been utterly righteous. The whole setup is built on that; it’s like a joke about a nun and a criminal. The joke only works because everyone assumes that the nun is very holy. This parable assumes that Pharisees were unimpeachable, and it then plays on that stereotype (this particular Pharisee was kind of chauvinistic) for effect. The take-away is not that “all Pharisees are hypocrites,” but rather that “Pharisees were so righteous that when one wasn’t, it was noteworthy.”

Maybe You Should Think About: The identities of these two men aren’t quite parallel. “Pharisee” is a religious identity; it is a partisan identification within second-temple Judaism. “Tax collector,” meanwhile, is an occupation. So it’s conceivable that one person could be both a Pharisee and a tax collector, the same way one might be a Methodist and an attorney. The structure of the parable, then, serves to denigrate religious categories as determinative of one’s worth before God, and elevate (or at least not penalize because of) occupational identity. The point isn’t that Pharisees were crooked; it’s that we shouldn’t depend on any religious identity to give us favor before God. God can’t be bribed, as Sirach says; God knows justified tax collectors and haughty religious folk, and God can tell the difference.