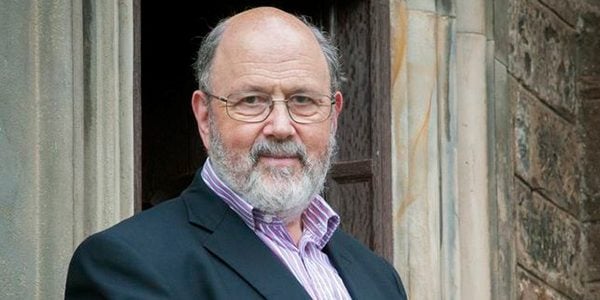

I got in trouble this weekend for a Facebook post in which I expressed regret about having interviewed NT Wright after he called transgender identity a “fashionable fantasy.” It was very mild compared to other things I’ve said online, but it struck a nerve with a lot of moderately progressive white Christian men (they were literally all moderately progressive white Christian men). Apparently expressing regret about having done an interview is the same thing as refusing to talk to anyone who disagrees with me. Then some of my transgender Christian friends tried to engage the conversation and all hell broke loose on my Facebook feed. Was it worth it? Maybe not. I’ve been wrestling with God about it.

I have many conflicting intuitions about the ethics of public theology. A problem with how we think about how we talk on the Internet is that we make false analogies. Even if I use the word “conversation” in a blog post about someone like NT Wright, he and I have never had a personal conversation and we never will have one. If I ever saw him at an event, I would be the three hundredth person in line to talk to him afterwards and I might get in a handshake after an hour of waiting. The closest thing to a conversation I’ve had with him was on our podcast when I asked him three questions and he responded with three 200 word 2 minute stump speeches in which he never stopped to breathe or say the word um.

Public conversation is not at all the same thing as personal conversation. When bloggers critique public figures, the public figure is not our actual audience; we’re speaking to the public figure’s audience or else our own. So when people respond with advice that applies to personal conversation, they’re missing the point. There is no way I will ever persuade NT Wright to change his mind about transgender identity. My words are not for him but for people who like me are beneficiaries of Wright’s incredible scholarship and are frustrated by the strange anomaly of his disdain for queer people that doesn’t fit with the rest of his theological framework. It’s very hard for me not to suspect that Wright is actually guarding his right flank by performing queerphobia in order to keep the evangelicals from burning his books.

So let’s talk about Matthew 18 since at least five people asked me if I had tried talking to Bishop Wright in private before criticizing him on the internet (since obviously I have his personal cell phone and email). In Matthew 18, Jesus exhorts his audience not to cast their dirty laundry out into public when they have a conflict with another church member. Here’s what he says exactly: “If another member of your church sins against you, go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone.” You’ll notice I italicized two parts. That’s because Jesus is describing a very particular circumstance.

First, this is not a public figure on the internet, but another member of your covenanted community. It is someone with whom you have enough personal standing to have a personal conversation. Second, this is someone who has sinned specifically against you. In other words, you are not representing anyone other than yourself in how you respond.

What are some modern examples for which Matthew 18 would pertain? Let’s say you’re on staff at a local church and a colleague undermines you in a leadership meeting. Or your fellow small group member is gossiping about you behind your back. Or someone you’re supervising is misbehaving in a way that you are held accountable for.

In all of these circumstances, it is appropriate to be discreet in your response so as to avoid scandal. It would be a disaster to adjudicate your conflict by subtweeting and vaguebooking on social media. So you speak with the other person privately, then take a witness, then go to the whole church (or the whole staff, small group, or appropriately sized group). And because you operate discreetly, you avoid creating unnecessary public scandal.

It’s an entirely different circumstance when you engage public figures who have already created a public scandal and to whom you do not have personal access. Jesus models this approach in a speech he makes about the Pharisees in Matthew 23:

The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; therefore, do whatever they teach you and follow it; but do not do as they do, for they do not practice what they teach. They tie up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on the shoulders of others; but they themselves are unwilling to lift a finger to move them. [vv. 2-4]

Notice how the circumstances are different. The reason Jesus does not follow his own protocol from Matthew 18 is because these aren’t other members of his personal congregation, but public figures who “sit on Moses’ seat.” They have to be engaged publicly since they are engaging in public acts that blaspheme God. The other key difference is that they aren’t just sinning against Jesus in which cause privacy and discretion might be the place to start. They are oppressing Jesus’ people by tying up heavy burdens for them to bear.

So Jesus deals with them brutally:

Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you lock people out of the kingdom of heaven. For you do not enter, and when others try, you stop them. Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you cross sea and land to make a single convert, and you make him twice the son of hell that you are. [vv. 13-15]

This is only a small piece of the diatribe that lasts 24 verses. Between this diatribe and Jesus’ property destruction in the Jerusalem temple, it’s clear why the religious leaders had to plot his death for the preservation of their power. It’s important to understand that when Jesus gives this speech, he’s not doing so for the spiritual edification of the Pharisees even though they are the official addressees. He’s doing so in order to name the oppression that his audience has suffered under their leadership. In each of the charges he levies, he is talking about how his listeners have been excluded and harmed by the Pharisees’ behavior.

In other words, Jesus shows solidarity to the victims of the Pharisees’ sin by dragging the Pharisees in his public proclamation. Matthew 23 is the equivalent of a viral twitter storm that took Jesus from being a troublesome faith healer to a public enemy who needed to be eliminated. If we look at what Jesus actually did to earn the cross that he carried to Golgotha hill, that helps us understand the meaning of his call to take up our crosses and follow him. Taking up your cross means putting your status and even physical life at risk by publicly standing up to the authorities in solidarity with those whom they crush. That’s not revisionist theology. It’s a straightforward reading of Matthew’s gospel.

Having said that, there are still other factors to consider. 1 Peter 3:15-16 offers great counsel for how we should conduct ourselves in public conversation as Christians:

Always be ready to make your defense to anyone who demands from you an accounting for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and reverence. Keep your conscience clear, so that, when you are maligned, those who abuse you for your good conduct in Christ may be put to shame.

People who speak uncomfortable truths with dignity and grace are going to be labeled vitriolic troublemakers no matter how cautiously they frame their words. But that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t try our best to speak with gentleness and reverence anyway. Not because our enemies deserve it because sometimes they don’t. But because integrity is one of the greatest powers we have.

As long as I speak with enough arrogance and malice that my words can be easily dismissed, I have betrayed whatever prophetic truth God has given me. I may satisfy myself and my amen chorus with a scorching take-down of an enemy. But what if all that the people who aren’t high-fiving me can see is my arrogance and malice? My audience is not just the people I’m criticizing and the people I’m championing but also the bystanders for whom my integrity matters.

If I am above reproach in how I speak, then those who hate me for speaking the truth will be put to shame. You cannot hate truth without being covered in God’s wrath and having your soul destroyed. I’m not just saying that about my adversaries; it happens to me as well. So the best I can do is to choose my words with intentionality, not to water down their meaning but to eliminate any excuse others have to misconstrue and dismiss them. Of course, it’s exhausting to try to speak perfectly, and trolls will always willfully misinterpret what you say in order to take you out of the game.

So I end in ambivalence. I do not regret showing solidarity to my transgender Christian friends by calling out NT Wright’s thoughtless, historically flawed transphobia. I do regret my failure to speak with gentleness and reverence and the contribution my lack of discipline has made to the ongoing decay of Internet discourse. Somehow I need to be willing to take the risk that Jesus took in Matthew 23 but also replace my impulsive rage with the love-rooted intentionality Peter proposes in 1 Peter 3:15-16.

Check out my book How Jesus Saves the World From Us!

55% of our campus ministry’s private support comes from blog readers like you. We have the only openly LGBT-affirming campus ministry in the state of Louisiana. We have lost a third of our funding in three years. Please help us thrive by becoming one of our monthly patrons so we can focus on our ministry!