Text

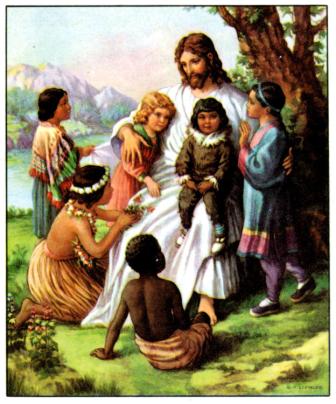

Then one of them, which was a lawyer, asked him a question, tempting him, and saying, Master, which is the great commandment in the law? Jesus said unto him, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

Matthew 22:35-40 King James Version

Commentary

Versions of this teaching of Jesus are captured in all three of the synoptic gospels, the texts closest to the actual life of the good rabbi. It is itself testimony to Jesus’ knowledge of the scriptures as it neatly puts together a commandment in Deuteronomy and another in Leviticus, giving us a vision that goes in two directions. The one toward the heavens, the other, toward the world we live in.

Now, I have to acknowledge I’m sort of a polytheist. That is one’s gods may be described as those things to which we give our attention. Which, frankly, for me is about the only really useful way of using words like “god” and “gods.” They are the things we attend to, and therefore have power over us.

And, maybe in that giving of attention there is the possibility of something more.

Exploring our lives through the lens of this definition, our gods are what we give our attention to, my goodness, there are a lot of deities out there. And not all of them are particularly attractive. Greed is one big god out there. No doubt. With all sorts of faces, grasping after money, chasing after sex, wanting, wanting. Another deity I notice highly worship is hatred, napalm like burning anger, again with many faces from irritation, to disdain. Probably the most insidious of the deities clamoring for our attention are various shades of certainty.

Now, we need to want things in order to keep alive, anger is a natural response to mistreatment, and, we need to make judgments in order to plan and accomplish. So, they have a place within the pantheon. The real problem with these gods and others like them is when they take up too much of our attention, they crowd out the rest of the world within which we live, and breathe, and take our being. Each wants to be the one and only. They are all of them jealous gods. As part of the background of life they actually have place, but when they put themselves on the central throne, then much ill follows. For ourselves and all those with whom we interact.

Enter Jesus. He distills the collective wisdom of the Jewish people and offers something powerful. He isn’t the only one. Hillel is a rough contemporary of Jesus, for instance, and who presents a healing distillation of the Jewish traditions. That acknowledged Jesus does something particularly magical with his approach to God. The stories of of the Jewish God coalesce over millennia becoming in his time the great creator and parent of humanity. Although, I think the early versions from storm god, to the particular god of a particular people, to something vast and universal are all there at the same confusing and contradictory time. In fact the version of this deity that I find most useful in my life is the one that can be found buried within the heart of the Book of Job. Not in the set pieces that frame that story where Job is rewarded, but rather in the midst of the terrible storm that over takes Job, and in that confrontation with what is. That’s the god I’m interested in. God as the great Is-ness of life.

And then Jesus takes that Is-ness and gives us a twist. He names the energy that connects the individual to that great Is that Is, and at the same time to brings it to one’s neighbor, which as I read it, seems obviously to mean the whole blessed world.

And he names it Love.

In Zen the word koan is meant to be an assertion about reality that includes an invitation to engagement. It is a map and a door. And, the thing in itself. And here we find Love is the great koan. And it has two faces, looking toward the great beyond, or, as I like, empty. And, looking toward each other, all the others.

Love is the map and a door. And the thing in itself.

I once read an etymological dictionary that claims the distant ancestor of the word Love comes from the hypothetical Indo-European word Lub – which means desire. A delightfully problematic term, I find. And, another way of saying “that to which we give our attention.”

Just this.

So, at one end of the deal we love love, we attend to the matter of passion and caring and attention, and compassion. An energy that leaps from our hearts into the very cosmos itself. It seems to have no point of origin, and in fact, seems to have no essence of its own. But, it leaps into existence wherever we attend.

And, we are in one beat of a heart, called to bring that attention to the world itself, to all the manifestations of neighbor.

Actually you can go in either direction. But, the catch is we need both. Love not writ large, not leaping out of the empty of the world doesn’t have perspective. And, love that does not leap from our meeting with each other has no significance.

I suggest a path here. Give our attention to the great generality, to, if you will, the Is that Is. And, at the next turn, turn that attention, that devotion, that love toward your neighbor. My neighbor. Our neighbors. Just this. Just this.

Or, the other way around. But both directions.

The path of the wise heart.

Verse

Holding a single flower

The wise smile broadly

The way is revealed