Today is the feast of the Epiphany. A wonderful celebration within the Christian tradition. And one that I as a Buddhist find worth reflecting on. Back when I was serving as a Unitarian Universalist minister I rarely missed an opportunity to visit this holiday. And, even today I continue to see value in it for all of us.

There are many perspectives on our human condition, and I’ve found whatever our particular path might be, we can be enriched by looking at how others engage the great questions of sorrow and healing.

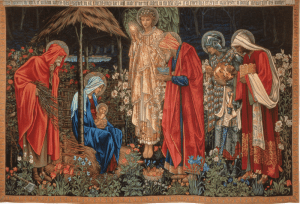

Also, I was raised Christian. And while Buddhism, particularly Zen Buddhism has proven to be more resonant with how I see the world, and with Zen has what I’ve found the most useful of all the world’s spiritual technologies, I still find much of value in my natal tradition. As a kid I loved, just loved the story of the magi, the wise men, the three kings. It’s just a great story, and with that story, comes a wonderful carol that perfectly captures its spirit. Who could want more? It really is part of our common Western spiritual inheritance. I would go farther and suggest it is a wonderful variation on the universal wisdom way.

Some years ago my spouse Jan and I were talking about that hymn associated with the feast of the epiphany, “We Three Kings,” when she shivered and shared her recollection of that year when she was about eleven and the costumes her mother dressed her, her sister and her brother in and the rickety church stage where they stood and held forth with a family rendition of the song, each kid taking a solo part.

It didn’t go well. She and her brother looked at their shoes and mumbled the words. Jan recalls choking out her part, “Sorrowing, sighing, bleeding, dying./Sealed in the stone-cold tomb,” wondering how she got saddled with those lines. On the other hand, her sister, maybe four at the time, discovered she liked the lights, stepping forward and belting her part to the rafters.

I asked Jan if she hated the carol to this day, and she said, nope. And then added, actually, it’s really kind of wonderful. And, I agree. The carol “We Three Kings” written in the middle of the nineteenth century by the Episcopal priest John Henry Hopkins, captured my imagination from pretty early on, and has stayed with me I think particularly because of those gifts, gold as the preciousness of life, frankincense as the prayers of the longing heart, and even in my youth, tellingly, compellingly myrrh for anointing the dead.

What are the real gifts of the spiritual life? This is an important question for those of us who’ve devoted our lives to spiritual quests. Well, I believe, here we are given a hint at what the real treasures are which we find at the heart of our searching. The carol itself has many versions, as, of course does the story itself.

The oldest version of the story of the magi, the three wise men visiting the newborn Jesus, is found in the gospel according to Matthew. It is probably worth noting that it doesn’t appear anywhere else in the Bible and what’s there is pretty sketchy. Much of what we know as the story is fill in from ensuing years. For instance, perhaps drawing upon the three gifts, which are there from the beginning, in the West three magi are named and given backstories. Matthew actually doesn’t even give us a number, much less names. In the Eastern churches there are in fact twelve magi. I prefer keeping it simple and focused, those three, and their haunting gifts.

Etymologically “magi” is a term associated first with Zoroastrianism and later with astrology, as most raised in the West surrounded by the warm, sometimes warm embrace of the Christian church might recall there’s a star in the story. But the part that caught my imagination is how there was some wisdom not necessarily connected to the Jewish or Christian traditions. Even before those doubts about how true the Christian story really was began to creep into my adolescent heart, I noticed this point implicit in the story; wisdom has never been constrained by a single spiritual tradition.

Wisdom. There is a wild and untamable spiritual insight, which erupts from our human hearts. It is called wisdom, often with a capital “W.” It’s found within the tradition, it appears pretty much in all traditions, but is not bound by it, not bound by any specific religion. In the Hebrew scriptures books like Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and for me most significantly Job belong to the wisdom tradition. Some argue the first psalm and in the New Testament the Christian letter attributed to James, Jesus’ brother also belong to wisdom.

A wisdom literature is common to the entire Near East. There are Egyptian versions, Persian versions. Some note that Job, or at least a hypothetical earliest version was adopted into the Hebrew scriptures from elsewhere in the Middle East or Egypt.

So, what is this wild and untamable wisdom? The wisdom perspective, at least as I’ve understood it has been that God, or the source, or the Deep, or the One, or, even the unnamable, or the Empty, choose your term for that which binds us all together; is not something beyond us, but something found in our everyday lives, both within and among us. Our lives are the wild. Our connections are the untamable. And here’s the irony. This wild and untamable is in fact only found within relationship. It might be dangerous, but it is intimate. And, therefore, wisdom is always practical, grounded, inevitably oriented back to our lived lives. This, I believe, is the great intuition, the mother of all useful spiritualities.

These days, thanks to a number of people, a good example might be Stephen Prospero, author of God is Not One, our attention has been drawn to how it’s a bit hard to find actual common threads in the world’s religions. The idea of a single mountain and many paths is vigorously challenged. And I think there’s truth in this. Robert Aitken Roshi used to say not many paths up that single mountain, but rather many paths and many mountains.

That said, I think there are human things. I think we do have some base line intuitions found as common human experience that are interpreted locally in a multitude of ways. And I suggest the wisdom traditions more closely track these universal intuitions than perhaps any other aspects of the world’s religions. Frankly, I think this wisdom perspective, finding the depths here, and concerned with what that means in the market place, in our homes, in our encounters with each other, makes more sense and ultimately is more compelling than stories of divine interventions from fire and brimstone falling from the sky to the birthing of deities.

If something is really true, natural, arising out of our humanity, there should be many variations on its themes found in many different cultures, ancient, and even modern. One of my favorite definitions from our contemporary culture of a genuine wisdom perspective, of our grounding and its consequences, comes from Albert Einstein. Now, there are variations of what he actually said in this regard, cited here and there. I kind of like that. Wisdom is frequently slippery. Best I can find the first version was reported in the New York Times, quoting a letter he wrote in 1950.

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us.” Okay, that’s the set up, the necessary predicate. What follows is Einstein’s articulation of the wisdom way. Albert sings to us, “Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.” He then adds a caution, a necessary modesty we all need to hear. “Nobody,” Albert reminds us, “is able to achieve this completely, but the striving for such achievement is in itself a part of the liberation and a foundation for inner security.” We are always a part contemplating the whole, the reed carved into a flute, recalling in its haunting melodies the reed bed.

Einstein’s wisdom perspective is pretty good. And it informs me. And, as I’ve said wisdom is found everywhere. Of course I’ve most been informed by Buddhist insights, Buddhist wisdom, which I think has more accurately noticed and explored this current than most religions.

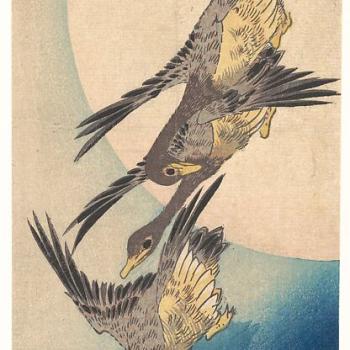

There’s an analogy popular in Buddhist circles, although I think it might in fact have a Sufi origin. Of course it’s an obvious metaphor for those who have the eyes to see. Should a wave realize it is part of the great ocean – that would be awakening. While as best we can tell a wave never knows its connections, the joy of our condition is that we humans can. For us it is discovering our individual lives, so precious, and passing, fleeting as smoke, are also at the very same time part of the whole, the great mess, all of it. I find it easy to see why we might name that great mess divine.

The critical point of our healing from the wound of separation turns on our understanding how we’re connected. Let’s step away from the image of wave and ocean. Wise not to be caught by one image, by one metaphor, by one analogy. Here’s another for the most important thing we can discover about ourselves. We are, each of us, the meeting of many strands in a vast web of relationship. Our finding this as our deepest truth and living from that knowing of our larger intimacy: that is wisdom. Whether we fancy it up with a capital “W” or not, that is wisdom.

All this echoing those gifts, I suggests, gold as the preciousness of life, frankincense as the prayers of the longing heart, and tellingly, compellingly myrrh for anointing the dead. Our living with these treasures is the way of the wise heart. As the Proverbs sing to us, “The wise in heart shall be called prudent: and the sweetness of their lips increasing our learning.”

We need to search no farther than our own hearts to find the treasures of the wise. Looking there, here, as Albert and so many others sing to us, “Our task must be to free ourselves… by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.” This is then tested within our encounters with each other. And proven by the lives we bequest to our children.

The great wisdom way.