Helder Pessoa Camara was born in Fortaleza, Ceara, Brazil, on this day in 1909. Today he is remembered as Dom Helder Camera, the late Roman Catholic archbishop of Olinda and Recife in that country, a fierce opponent of the military dictatorship, and an advocate of Liberation Theology.

There is in fact a move within some circles of the Catholic church to canonize him. I find it about as likely as Dorothy Day or that other troublesome priest Thomas Merton getting the nod from the official church. But, of course, one never knows, and that spirit does indeed rest where it will.

Should that unlikely event ever happen, his feast would most likely be the day of his death, August the 27th. Me, as I’ve opined elsewhere, while I have no brief against commemorating someone’s life on the anniversary of their death, after all it marks the end of a life, and one can take into account the fullness of their life that way. But, I like birthdays. They mark out all the possibilities, the potentials, and in some ways, that becomes something we all share in the natal moment, or, at least, most of us: hope.

Dom Camera is most famous for a sentence. “Quando dou comida aos pobres, chamam-me de santo. Quando pergunto por que eles são pobres, chamam-me de comunista.” It is usually translated into English as “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.” Within that sentence is the birthing of another hope, liberation theology.

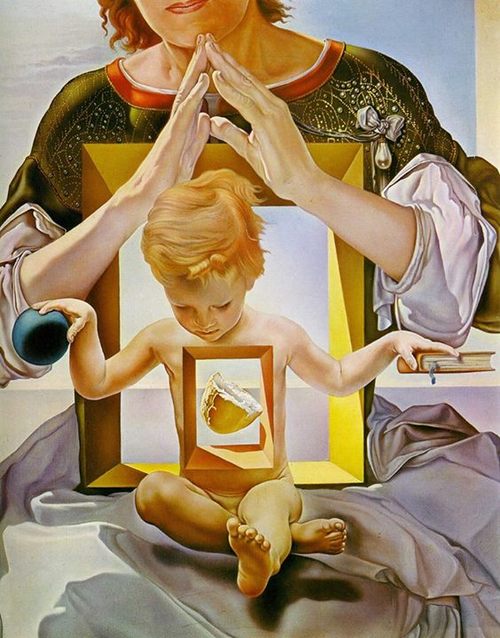

Liberation theology arose in Central America when Catholic theologians began to question why such concentration of wealth among so few, and why so many suffered so terribly. Just that question. They began to search their own tradition for answers and for direction. And they saw that the person they think of as God on earth, came not as a king but as a peasant, as a carpenter. They found particular wisdom in what is called the Sermon on the Mount. And, most of all, they found in Mary, another peasant who would be Jesus’ mother, an exemplar of the lowly being raised on high by God, and as God’s calling as the work of this world.

In particular they looked at her song, which in that story, came unbidden from her lips at the moment she learned she was to be the mother of God. It is called Mary’s song, or the Magnificat, and is captured for us in the Gospel according to Luke. In the King James version it sings to us:

And Mary said, My soul doth magnify the Lord,

And my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour.

For he hath regarded the low estate of his handmaiden: for, behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed.

For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is his name.

And his mercy is on them that fear him from generation to generation.

He hath shewed strength with his arm; he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.

He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low degree.

He hath filled the hungry with good things; and the rich he hath sent empty away.

He hath holpen his servant Israel, in remembrance of his mercy;

As he spake to our fathers, to Abraham, and to his seed for ever.

I don’t think it that hard for any of us, whatever our faith, to listen to these words with open hearts, and not see the roadmap to the true revolution, to the realm of God, the Pure Land, to the true home for the family to which we all belong.

Now, Dom Helder was a complicated person. And certainly not all peaches and cream. In his youth I gather he flirted with Brazilian neo-fascists. And, later he supported contraception until he didn’t. But, there was a trajectory, a constant self-evaluation, as well as a hard, hard look at the world in which he lived, that makes him, for me, at least, an attractive figure. I can see myself in him.

He admired the Marxist analysis of capitalism, although he had no taste for its conclusions. The celebrity journalist Oriana Fallaci quoted him from an interview calling himself a socialist. He then unpacked how he meant the word. “My socialism is special, its a socialism that respects the human person and goes back to the Gospels. My socialism it is justice.” Here the word socialism becomes a shorthand for our care for the world, and particularly a focus on the poor, the downtrodden, the left behind.

As someone deeply concerned with Engaged Buddhism, I am aware of commonalities, challenges, and possible cross fertilization of these two currents, Liberation Theology and Engaged Buddhism. I’m hardly alone in this. And there’s a lot to be found within that conversation. Each brings a deep intuition of interconnection, each brings compelling images and, and each has shortcomings and drawbacks.

Professor and Lama John Makransky writes as a Buddhist observing Christians, “In terms of Christian liberation epistemology, even taking into account the historical situation that liberation theologians speak from, one weakness is a tendency to construct and reify a duality between those who are preferred by God and those who are not, a duality that makes it difficult, practically speaking, actually to love each person unconditionally in the way that Jesus taught.” This dualism is a problem I find that cuts right through Christianity. And is obvious as a problem within liberation theology.

And, of course, this is true latently, for Buddhists, and all human beings. We naturally slice and dice and in the process create dualisms that are useful – until they’re reified. Resisting the impulse to other others is a constant struggle, as it is a natural part of our consciousness.

Of course, there’s a lot to criticize for Buddhism, as well. And so the lama continues “On the other hand, Buddhist epistemology lacks the concept of a God who chose to incarnate uniquely among the most marginalized and rejected, and the related Christian concept of social sin.” And that’s the other problem within spiritualities, getting lost in the great empty, in the non incarnated. Buddhists can be so caught up in the non dual that it forgets the separations and distinctions, and the consequences of actions, except as some bloodless abstraction leading to a chain of births.

Buddhism can help Christians expand, and, if you will, reframe their identity with the poor to include the entire world, the cosmos itself. And, Professor Makransky suggests, “Christian liberation theology (can help to) reframe Buddhist understandings of compassion and its cultivation, and stimulates new insights into current social implications of ancient Buddhist teachings of karma, interdependence, and bodhisattva practice.”

Each of the traditions Liberation Theology and Engaged Buddhism has a growing literature as well as a history of engagement. And, increasingly each is informing the other in dialogue. And, importantly, each is growing deeper, more true, more hopeful.

For me the nexus point is Guanyin. As she seems always to be.

I’ve written about when we first arrived in Long Beach, California, one Sunday evening as Jan and I were driving along Ocean Boulevard we noticed the Mary shrine attached to a Buddhist Monastery was particularly lovely, with flowers and candles already lit and maybe half a dozen people there offering prayers. It was all quite wonderful. I recall the first time we drove by that corner of Ocean and Redondo and saw what appeared to be a couple who were either East Asian or both of East Asian descent dressed formally in suit and a very nice dress giving a Buddhist style standing bow in front of the image. It left me wondering what was what.

It was hard to say if the building to which it was attached had originally been a mansion, like most of the buildings on that stretch of Ocean Boulevard, which looks unobscured across the street and over the bluff to the harbor. This is beautiful. Startlingly beautiful. Or, I wondered, whether it had been a religious institution originally, put up before this was quite the upscale real estate it has become. I kept meaning to look it up, and finally did. Turns out the building originally served a Carmelite convent, a cloistered community of nuns informed by the mystical tradition of St Theresa of Avila and St John of the Cross. When the nuns decided to relocate to a less public area it was purchased by the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, a very traditional Chinese Buddhist monastery.

Apparently the nuns requested that the shrine be kept intact. And from the official notice at the monastery’s website, they agreed without hesitation, stating they saw Mary as the Western version of Quanyin. As good as their word, the monastery has kept the shrine in beautiful condition. And, today Christians and Buddhists both pay homage at the shrine. As I was digging around the web one commentator added in how as the image is Mary Star of the Sea, it includes a gigantic clamshell as a background, introducing a hint of another sacred feminine image, Aphrodite. It is enough to make a Jungian swoon…

More importantly it is Guyanyin as Mary, or, perhaps it is Mary as Quanyin that points to our liberation.

There’s a koan. It’s collected in the Blue Cliff Record as case 89.

Yunyan asked Daowu, ‘How does the Bodhisattva Guanyin use those many hands and eyes?’ Daowu answered, ‘It is like someone in the middle of the night reaching behind her head for the pillow.’ Yunyan said, ‘I understand.’ Daowu asked, ‘How do you understand it?’ Yunyan said, ‘All over the body are hands and eyes.’ Daowu said, ‘That is very well expressed, but it is only eight-tenths of the answer.’ Yunyan said, ‘How would you say it, Elder Brother?’ Daowu said, ‘Throughout the body are hands and eyes.’

Both Yunyan and Daowu were students of the same teacher and would themselves each become famous teachers. According to some traditions they were actually brothers, but for various reasons this seems unlikely. More interesting to me is how Zen is organized in lineages; that is my teacher had a teacher who had a teacher, in a line that historically goes to early medieval China and mythically all the way back to the Buddha. For me a really interesting thing is how Yunyan is my teacher’s teacher’s teacher in an unbroken line running from my life back to the beginning of the ninth century.

But the really important thing for us is that both these monks had their ideas of self and other collapse and saw deeply into authentic interconnectedness. At the time this story takes place Daowu perhaps sees a bit deeper than his dharma brother. Although perhaps not. In the great way we play a lot, each of us taking different parts in turn, and play is in fact one of the primary spiritual disciplines. That noted, in this conversation we get a sense of what it means to move from the interdependent web as a really good idea, to where it describes who we actually are.

Now Guanyin is the archetype of compassion. Sometimes portrayed as a man, sometimes as a woman, occasionally in an androgynous form: but always as the deeply, profoundly felt impulse to reach out. This reaching out is the body of awakening. And Daowu says of this need to act, that it comes not through an interpretation of the image of the interdependent web, not through reading the Wealth of Nations, not through solid Marxist analysis, not actually through an investigation of Mary’s hymn in the Gospel According to Luke (although, yes, I do believe Mary is Guanyin and that Guanyin is Mary), not through righteousness of any sort, certainly not righteous anger, a dreadful seducer beckoning us to a confusion of ends and means: but rather like someone turning in her sleep and reaching a hand behind her head to adjust her pillow.

Just this. Ends and means, one thing; our interdependence and you and I, one thing.

Engaged Buddhism. Liberation theology.

Now an old Zen saying has it that even the Buddha is continuing to practice. And understanding the relationship between our separate identities and the web itself is complex. So, Yunyan’s eighty percent is that this realization is like having eyes and hands all over our bodies. True, true, says his brother. But one hundred percent is that those eyes and hands are our body. No separation, however slight and the universal comes to be known the only place it can be known, in each particular instance, in each particular person.

Engaged. Buddhism. Liberation. Theology.

Like Mary confronted with the great mystery singing her canticle. Like a dreamer reaching behind her head in her sleep and adjusting her pillow.

And so, this practice of refinement continues, and continues. And the path becomes one of ever greater intimacy. Each of us coming to know the other as we all walk the great way together constantly transformed and transforming.

Just this…

Just this.

Just

This