Editors’ Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on Heroes of 2014. Read other perspectives here.

How could it be? That the friend and colleague of African-American leftist philosopher Cornel West, with whom he team-teaches seminars at Princeton, and presidential appointee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights, is called a racist?

Why in the world would the man whom Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan praised as “one of the nation’s most respected legal theorists” known for his “profound and enduring integrity,” be labelled a misogynist?

Why would a man who once worked for George McGovern get a death threat from a self-styled “pro-choice terrorist”?

Why would the man who holds the same endowed chair once held by Woodrow Wilson have his class disrupted by protestors from time to time?

The answer to all these questions is simple. This man dares to challenge the cherished dogmas of secular orthodoxy.

Robert P. George holds Princeton University’s McCormick Chair in Jurisprudence, and is vice-chairman of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

In the past year he has been on the front lines of the great debates of our day. Unlike many intellectuals, he is not afraid to take on the most politically-correct shibboleths of today’s culture—that abortion is a basic human right, that gay marriage is the moral equivalent to heterosexual marriage, and that those who hold to the second are bigots who deserve moral and civil censure.

George grew up in West Virginia as a loyal Democrat, the grandson of immigrant coal miners. He led the West Virginia Democratic Youth Conference in 1972, but left the party when it became clear it was committed to abortion on demand.

After studying law and religion at Harvard, and then earning a Ph.D. in philosophy of law at Oxford, George became known for his commitment to natural law as a source for understanding moral principles discernible by reason. Natural law goes back to Aristotle, Plato, and Aquinas– among many other ancient and medieval thinkers—and, according to George, was important for America’s Founders such as Madison and Jefferson. Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. also used it to construct their political philosophies.

George argues that natural law, a set of inherently knowable moral truths, is a critical tool against a “secular orthodoxy” that roots much of its thought in David Hume’s proposal that human nature is simply a collection of desires that demand gratification. Hence morality for Hume and his postmodern descendants is simply subjective, coming from within ourselves, balancing our selfish desires with the demands of those outside ourselves. Natural law, in contrast, comes from outside, and tells us there are moral truths that are there—written into the fabric of the cosmos as it were–whether we desire them or not.

For example, George insists that reason can show us the sanctity of human life, which means “the inherent and equal worth and dignity of each human being—irrespective not only of race, ethnicity, age, and sex but also of stage of development, mental or physical infirmity, and condition of dependency” (Conscience and Its Enemies, p. 194).

George argues that scientific evidence is overwhelming that human life begins at conception: the fusion of egg and sperm produced a new, complete, living organism that is internally directed and will develop into an infant and child—if it is not killed first.

The question is not whether human embryos are human beings, but whether we ought to respect and defend these little human beings.

His Princeton colleague, philosopher Peter Singer, denies equal dignity for all because, he says, personhood depends on autonomy. So those in the embryonic, fetal, and infant stages of development, as well as those at later stages who have lost capacities for autonomy, do not deserve protection.

Professor George objects. Who of us is completely autonomous and not dependent to some degree?

The second and bigger fight today is over marriage. George has just published his co-authored Conjugal Marriage: What Marriage Is and Why It Matters (Cambridge, 2014) . He argues there that marriage has always been understood as the only human community that is oriented to procreation and to bodily, emotional, and spiritual union. When it is defined now—for the first time in human history by a state—as sexual-romantic companionship, it is impossible to say why such companionship should be exclusive or life-long. Or why it should be restricted to two people. Not only will children be hurt by these constantly-evolving relationships, but so will citizens who have little to direct them but these chameleon-like definitions.

The second battle over marriage leads to the third, for religious freedom. For, George argues, we all were mistaken to believe the “grand bargain”—that if conservatives would accept the legal redefinition of marriage, liberals would respect conservatives’ right to act on their consciences without penalty. Instead, bakers and photographers are losing their businesses because they refuse to violate their convictions. And all who disagree will suffer in some way, if only by being forced to be silent.

“Liberal secularism will tolerate other comprehensive views so long as they present no challenge or serious threat to its own most cherished values. But when they do, they must be smashed—in the name, for example, of “equality” or preventing “dignitarian harm”—and their faithful must be reduced to dhimmi-like status in respect of opportunities (in employment, contracting, and other areas) that, from the point of view of liberal secularist doctrine, cannot be made available to them if they refuse to conform themselves to the demands of liberal ideology.” (2014 Diane Knippers Memorial Lecture, IRD)

Recently, perhaps in 2014 more than ever, Professor George has become something of a prophet. He warns Christians that “comfortable Christianity is no longer possible.” Good Friday is coming. At the National Catholic Prayer Breakfast this year he asked, “Where will we be then? Will we be the disciples who fled? Will we be like Peter who denied his Lord three times?”

He warns that many Christians will seek a way to avoid the cost of discipleship. They will make trade-offs. At King’s College in New York City, he told the new president that the task before him and his faculty was to train his students to be martyrs. Not to lose their physical lives, but their friends, family, professional opportunities, and social standing.

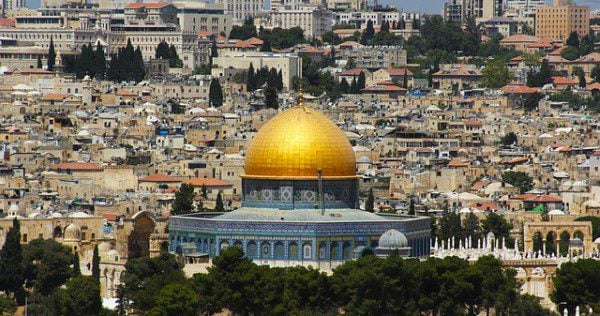

George advises that evangelicals work together with Catholics and Eastern Orthodox, and with Mormons and Muslims and Orthodox Jews. For all these religious communities have a stake in the battles for life, marriage, and freedom of conscience.

Perhaps his best advice to us all is his admonition not to be defeatists. We were defeatists once on abortion, and yet we are now winning the war. In the 1970s we were told we were on the wrong side of history, yet every year the percentage of pro-life Americans goes up, especially among the young. Now it is a majority of the American public.

In the 1920s and 1930s eugenics was embraced by most elites, including the mainline Protestant churches. “It seemed like a juggernaut.” The eugenicists thought their opponents—Catholics and evangelicals—were “on the wrong side of history.” But then the tide turned against eugenics.

George exhorts us to “stand up, speak out, fight back, resist! Do not be demoralized. Refuse to be intimidated. Speak moral truth to cultural, political, and economic power.” (Knippers Lecture)

Professor George does all these things, while showing respect for those on the other side, and maintaining friendships with those who disagree.

This is why Robert George is my Man of the Year. In a day when Christians and conservatives are demoralized by cultural tsunamis, when the gospel seems under attack like no time in recent memory, he shows us how to be brave. And how to make a difference, with intelligence and grace.