It is a beautiful autumn evening. As the cool breeze sweeps over rivers and mountains, a woman creates an altar outdoors in honour of the Full Moon. Offerings of autumn’s bounty – chestnuts, pumpkin, wine, potatoes, and home-made sweets – are carefully stacked upon a raised platform, and beside it is placed a vase of autumn greenery. The woman gazes at the Moon, drinking in its beauty and its mysterious power, and she may even be inspired to write poetry about the scene. Once her contemplation of the Moon is over, she and her family eat the offerings together, thankful for the gifts that Nature provides.

This may sound like a typical Full Moon ritual performed by Neopagans all over the world. But this isn’t a Neopagan ritual. This is a ritual for Tsukimi – Japan’s annual Moon Gazing Festival.

Like many of Japan’s festivals, Tsukimi (usually referred to with an honorific “o”, O–tsukimi, in Japan) has its origins in China, where it is known as Zhōngqiū Jié – the Mid-Autumn Festival. It may date as far back as the Shang Dynasty (16th to 10th century BCE) and was held in order to commemorate a successful harvest. It was a time to give thanks to the spirits of nature for their gifts. Today it is celebrated in countries throughout East Asia, including Korea, Vietnam and, of course, Japan, on the 15th day of 8th month according to the Chinese calendar. This usually translates as the September 15th of the Gregorian calendar (this year, the Full Moon will fall on the 16th, so I will probably celebrate Tsukimi then).

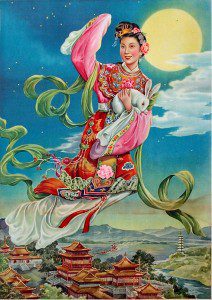

In addition to celebrating the the autumn harvest, the Mid-Autumn Festival is linked to Moon worship. In China, the Moon is revered as the goddess Chang’e. At the Mid-Autumn Festival, offerings are made at altars to Chang’e facing the Moon, in the hope that she will bless her worshippers with beauty. In Japan, the kami of the Moon, Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto, is usually thought to be male. However, his name or image do not usually feature in Tsukimi imagery. Perhaps this is because Tsukuyomi is sometimes portrayed as rather sinister; according to the Kojiki (Japan’s ancient record of myths), Tsukuyomi angered the kami of the sun, Amaterasu Ōmikami, by killing the kami of food. Or perhaps it is because Tsukimi is of clear Chinese origin, so it is not as strongly associated with the kami of Japanese origin.

The image you are likely to see at Tsukimi, both in China and Japan, is the rabbit. Rabbits and hares have lunar associations in many countries and East Asia is no exception. Throughout East Asia, people interpret the markings on the full Moon to be a rabbit (whereas Westerners often see them as a face). The Chinese say that the rabbit is a companion of Chang’e, while according to a Buddhist legend known throughout Asia, the rabbit was put on the Moon to reward him after performing a deed of self-sacrifice. According to Japanese tradition, the rabbit in the Moon is making mochi (sticky rice cakes) with a hammer and mortar; you’ll therefore see lots of depictions of rabbits eating or making mochi at Tsukimi.