(Pagans don’t proselytize, and the majority of us don’t have Pagan parents; as a result, people come to Modern Paganism through various means. For many of us, books, movies, and music provided the impetus to walk the Pagan Path. Gateways to Paganism is one guy’s attempt to document some of the things that have led various people to Paganism, and why those things had that effect.)

(Pagans don’t proselytize, and the majority of us don’t have Pagan parents; as a result, people come to Modern Paganism through various means. For many of us, books, movies, and music provided the impetus to walk the Pagan Path. Gateways to Paganism is one guy’s attempt to document some of the things that have led various people to Paganism, and why those things had that effect.)

I am not good with movies. If it doesn’t have a superhero or an elf in it I’ve probably never seen it. Such has been the case with The Wicker Man (The 1973 version of course) for the last forty years. Oddly I’m a big fan of horror movies, but I somehow just never got around to The Wicker Man. I’ve known of the movie of course, and due to various conversations over the last twenty years knew exactly how it would play out when I finally sat down to watch it this weekend. The Wicker Man isn’t the perfect Beltane movie, but it’s close in a weird sort of way. As a Pagan (and perhaps more specifically a Pagan steeped in the myth of the eternal English Scottish countryside) there were just moments in this film that had me going “holy shit” this is awesome. (Warning now, spoilers ahead. This edition of Gateways to Paganism assumes you’ve seen The Wicker Man or don’t mind me spilling some of its secrets.)

There have been some important mainstream movies in relation to Paganism over the last forty-five years, and if The Wicker Man is not number one, it’s definitely in the top three (the other two being Rosemary’s Baby from 1968 and The Craft in 1996). A quick summary of the movie doesn’t do it justice and is really not the point of this article but I feel like it’s necessary. To put it simply a rabidly Christian police sergeant named Neil Howie visits an isolated Scottish island in search of a young girl after receiving a letter that she’s missing. The locals give Sargent Howie the run-around in his search, but he’s also kind of an asshole about the whole thing because the island is full of Pagans! People run around naked and have sex publicly in the great outdoors. Children are taught about the regenerative forces of nature etc etc. Technically The Wicker Man is a horror film because the Christian Sergeant is burned to death at the end as a sacrifice to the God of the Sun and the Goddess of the Fields, but up until then it’s all pretty awesome.

There have been some important mainstream movies in relation to Paganism over the last forty-five years, and if The Wicker Man is not number one, it’s definitely in the top three (the other two being Rosemary’s Baby from 1968 and The Craft in 1996). A quick summary of the movie doesn’t do it justice and is really not the point of this article but I feel like it’s necessary. To put it simply a rabidly Christian police sergeant named Neil Howie visits an isolated Scottish island in search of a young girl after receiving a letter that she’s missing. The locals give Sargent Howie the run-around in his search, but he’s also kind of an asshole about the whole thing because the island is full of Pagans! People run around naked and have sex publicly in the great outdoors. Children are taught about the regenerative forces of nature etc etc. Technically The Wicker Man is a horror film because the Christian Sergeant is burned to death at the end as a sacrifice to the God of the Sun and the Goddess of the Fields, but up until then it’s all pretty awesome.

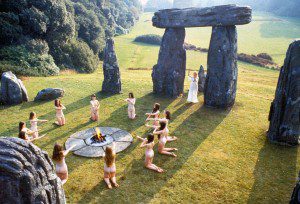

Despite the gruesome end to Sergeant Neil Howie most of the movie shows an imaginary and mostly ideal Pagan world. Sexuality is celebrated and there’s this lovely intermingling of the modern and natural worlds. A maypole in the middle of town (just on the eve of Beltane) is an accepted part of everyday life, and most of the townsfolk seem like nice folk (if a little creepy now and again, but just a little). That the Lord of Summerisle is Christopher Lee himself makes things even cooler. Who wouldn’t want Christopher Lee as the Lord of their island?

What makes The Wicker Man so important historically in context to Modern Paganism is that much of it simply feels like Modern Paganism. The Wicker Man was the first movie to share rituals that look passably Pagan. It’s all just in bits and pieces but I’ve been to rituals with lovely naked people jumping over a small fire. (A scene that leads to the Christian Sergeant exclaiming “But they are… are ‘naked'” with Lee’s Lord Summerisle replying with “Naturally! It’s much too dangerous to jump through the fire with your clothes on!”) Maypole dances and processional revelry . . . . forty years ago you most likely took what you could get in regards to seeing anything that might be thought of as “Pagan.”

What makes The Wicker Man so important historically in context to Modern Paganism is that much of it simply feels like Modern Paganism. The Wicker Man was the first movie to share rituals that look passably Pagan. It’s all just in bits and pieces but I’ve been to rituals with lovely naked people jumping over a small fire. (A scene that leads to the Christian Sergeant exclaiming “But they are… are ‘naked'” with Lee’s Lord Summerisle replying with “Naturally! It’s much too dangerous to jump through the fire with your clothes on!”) Maypole dances and processional revelry . . . . forty years ago you most likely took what you could get in regards to seeing anything that might be thought of as “Pagan.”

The Wicker Man also speaks to the writings of Margaret Murray, James Frazer and other early Twentieth Century scholars who had a lasting impact on what would become Modern Paganism. Summerisle is the kind of place that Murray hints existed just a few hundred years ago in The Witch Cult in Western Europe, with every British Beltane tradition being an ancient pagan relic no matter its true date of origin. Sergeant Howie is sacrificed because he’s the substitute for the actual Lord of the Isle and set himself up to be so by donning the clothes of the Lord of Misrule.

The Wicker Man also speaks to the writings of Margaret Murray, James Frazer and other early Twentieth Century scholars who had a lasting impact on what would become Modern Paganism. Summerisle is the kind of place that Murray hints existed just a few hundred years ago in The Witch Cult in Western Europe, with every British Beltane tradition being an ancient pagan relic no matter its true date of origin. Sergeant Howie is sacrificed because he’s the substitute for the actual Lord of the Isle and set himself up to be so by donning the clothes of the Lord of Misrule.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMSFSG7NVIo

Willow’s Song

The idea of the sacrificial deity and later sacrificial king (and his sometimes substitute) were ideas essential to both Murray and Frazer and were ideas popular in the Modern Paganism of the 1960’s and 70’s. (Not that Pagans were sacrificing folks, but the idea of a sacrificial king in the history of the English monarchy was a strong one in Murray’s writings, especially her final work on Witchcraft The Divine King in England.) There’s not much in The Wicker Man that feels out of place, well until the death of the movie’s sort of hero in a giant burning Wicker Man at the end of the film, but even that comes with caveats.

The people of Summerisle give Sergeant Howie all sorts of “outs” to keep from ending up as the island’s sacrifice. The gorgeous Britt Ekland (as the character Willow) attempts to seduce Howie at one point, but his misguided sense of morality keeps him from sharing her bed. Sexually active folks make poor sacrifices apparently, the island demands a virgin; the moral of the story is apparently that having sex will save your life. Howie also willingly comes to the site of the sacrifice and knocks out a creepy inn-keeper in order to don the bells of Punch, the jester and substitute for the actual “king” of the isle. Most of us would have had very little to fear on Summerisle because we’d have either wound up in Willow or Lord Summerisle’s respective beds.

Maypole

A lot of what makes the film work are the musical numbers sprinkled throughout. Music is so essential to The Wicker Man that it might nominally even be thought of as a musical. Everything on the soundtrack is credited to the band “Magnet” (a studio band created to record the movie’s soundtrack) but the soundtrack’s composer (and in some cases assembler) was American Paul Giovani. Giovani’s movie soundtrack is an ingenious collection of Middle English folk, poetry by Robert Burns, and all new compositions. The movie’s most famous tune, Willow’s Song, is littered with double entendres that were rather racy on the big screen back in 1973. It would have been nice if I could justify using some of the soundtrack for my own Beltane revels, but most of them are just off enough that I can’t bring myself to do it. I really dig the song Maypole for example, but theologically it’s pretty unbalanced, with a little too much wand and not enough grail.

And on that bed there was a girl

And on that girl there was a man

And from that man there was a seed

And from that seed there was a boy

And from that boy there was a man

And for that man there was a grave

From that grave there grew

A tree

Just a little bit of womb in there would have gone a long way.

While watching the film I could never quite decide if Sergeant Howie was the protagonist or the antagonist. There’s just enough antagonism (and possibly truth) directed at Christianity that as the movie rolls along it gets easier and easier to root for the Heathens. The Wicker Man (or most likely the novella on which it was based entitled The Ritual) wasn’t written as cultural commentary, but it provides some interludes in that direction none the less. I know it’s completely geeky and nerdy but anything Christopher Lee says just seems to have an extra degree of importance to attached to it. When his Lord Summerisle speaks to the failures of Christianity I can’t help but nod in agreement.

Sergeant Howie: And what of the true God? Whose glory, churches and monasteries have been built on these islands for generations past? Now sir, what of him?

Lord Summerisle: He’s dead. Can’t complain, had his chance and in modern parlance, blew it.

_____Lord Summerisle: I think I could turn and live with animals. They are so placid and self-contained. They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins. They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God. Not one of them kneels to another or to his own kind that lived thousands of years ago. Not one of them is respectable or unhappy, all over the earth.

The use of “Wicker Men” in history is dubious at best (if they existed we should have come across their remains by now and we haven’t) but the influence of The Wicker Man on Modern Paganism is less so. Back when Paganism was still on the very edge of public awareness out came a movie that very nearly celebrated it. Certainly The Wicker Man doesn’t represent Modern Paganism in any real sense, but in brief flashes it looks and feels like something familiar. The Goddess is alive and magick is afoot, just be careful as to what costumes you put on the first of May . . . . . and if a future (James) Bond-girl attempts to seduce you, by all means go along with it!

The use of “Wicker Men” in history is dubious at best (if they existed we should have come across their remains by now and we haven’t) but the influence of The Wicker Man on Modern Paganism is less so. Back when Paganism was still on the very edge of public awareness out came a movie that very nearly celebrated it. Certainly The Wicker Man doesn’t represent Modern Paganism in any real sense, but in brief flashes it looks and feels like something familiar. The Goddess is alive and magick is afoot, just be careful as to what costumes you put on the first of May . . . . . and if a future (James) Bond-girl attempts to seduce you, by all means go along with it!

(There’s more in this series too: Silver Ravenwolf, Paul Huson’s Mastering Witchcraft, Tori Amos, and Led Zeppelin.)