I always considered myself honest, and I had a lot of pride attached to that. I had a boss once who would stare you in the eye and just flat-out lie — I mean on the level of “The sky is green.” — daring you to challenge him. No one would, and we’d move forward as a company based on the sky being green. I was never that kind of liar.

As a teenager, when my friends snuck out at night or created cover stories of sleepovers and studying, I simply disobeyed my parents and accepted the consequences.

But there are other kinds of lies.

Let’s say you invited me to a dinner party and I had no intention of going. Odds are I’d say, “I’ll try to make it.” You’d get enough food and refreshments to include me. I’m not saying I’m that important, but if we’re close then during the party you might have a nagging hope I’d make it — and a quietly growing frustration with me for not showing up. By avoiding the slight awkwardness of the moment when you invited me, I might have caused lingering damage to our friendship.

I used to surround myself with untrustworthy friends. We’d profess undying devotion and then never show up for each other. It let me off the hook for being untrustworthy myself. But these days, I want to live with all my cards on the table.

I want to speak plainly about lying. Is it ever OK? My gut reaction is no. But it’s interesting how quickly this can get messy.

Let your ‘yes’ mean yes

There’s a saying: If you want to have self-esteem, do estimable acts. You cannot force someone to trust you. But you can choose to be honest, and when you are consistently honest with others, you gain their trust.

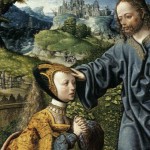

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus expands the Commandment to not bear false witness against a neighbor into a ban on making all oaths. He concludes with a statement that, when I first read it long ago, jumped off the page and burned itself onto my heart: “Let your ‘Yes’ mean ‘Yes,’ and your ‘No’ mean ‘No.'” (Matthew 5:37)

The footnote in the New American Standard Bible bluntly explains: “Jesus demands of his disciples a truthfulness that makes oaths unnecessary.” Quakers and Mennonites refuse to swear under oath to tell the truth, because to do so would suggest that without the oath, they might not.

Not lying is a good practice in general, and it’s a key principle in many religions. One of the five Buddhist precepts is to “refrain from false speech.” The principle of satya, or “truthfulness,” in Yogic philosophy and Hinduism says “not to speak untruth physically, vocally or mentally.” And adds, “Speech should be used for the service of all,” delivered with “softness,” “sweetness” and “kindness.” Similarly, Ephesians 4:15 counsels to speak “the truth in love.”

Ironically, many think they are lying to maintain kindness and harmony — pretending to like the neighbor you hate; keeping family secrets; and just generally avoiding awkward situations and hard truths. But this is a fake harmony based on pretending past problems and differences don’t exist, depriving us of the possibility of deeper union.

I was raised by a mother who, with good intentions, explained her Byzantine structure of white lie rules to me so I would understand how to be a polite member of society. She meant well but from a very early age I found this disturbing. Something inside me knew it was wrong. Something inside me believed Truth was always best.

And yet, I lied. Not big fat lies for personal gain; not my mother’s “niceness.” My lies were based in fear — fear that without them you wouldn’t like me, or find me attractive or interesting; that you wouldn’t include me or respect me.

Would I lie to you?

Great thinkers and spiritual leaders have grappled with the question of whether it’s ever OK to lie with varying results.

The Dalai Lama, in Ethics for the New Millennium, takes on the classic thought experiment: You see a man fleeing people who want to kill him; they ask which way he went. Not harming is the higher purpose, he concludes, and may justify lying.

In On Lying, St. Augustine takes an absolutist position. He points to Psalm 5 — “You destroy those who speak lies; the Lord abhors the bloodthirsty and deceitful” — and asks, How can one ever prevaricate if the Lord abhors liars and will destroy them? St. Aquinas, in Summa Theologia, says “every lie is a sin,” but offers gradations of sinfulness with lies done in jest or with good intentions pretty far down the list.

So what about good intentions? Surely, the Dalai Lama’s liar means well. Am I just oversensitive on the issue because of my upbringing?

Dr. Scott Peck, in The Road Less Traveled, says, “First, never speak falsehood.” Peck might allow that you could refuse to answer the hypothetical pursuers, but not say, “He went thatta way” and point in the wrong direction.

Even withholding truth, Peck says, should always be treated as a serious moral decision and the primary factor should always be the person-lied-to’s “capacity to utilize the truth for his or her own spiritual growth.” If, for example, parents tell a child early on they’re considering divorce, they will simply scare the child, who doesn’t have the capacity to use this information in a healthy way.

The problem with these evaluations is that they only work if you are well intentioned and loving in your discernment, and the mind left to its own devices has an amazing ability to rationalize self-serving behavior.

Brad Blanton, psychologist and author of Radical Honesty, is having none of it. He argues that there’s never a situation served by dishonesty. Blanton challenges each of us to clear up lies from the past; honestly express current feelings and thoughts; stop playing a role; and just be our authentic self.

His compelling thesis is that relationships based on untruth cannot be deep or rewarding. To my mind Blanton is missing one key ingredient: the concern expressed in all spiritual traditions for combining honesty with love and kindness. His version of radical honesty sounds kind of obnoxious.

All too often, I see honesty used as a weapon, as carte blanche for being a jerk, with the self-righteous truth teller hiding behind, “I’m only being honest.”

Growing up in all aspects

Perhaps there is no easy answer. When Ephesians 4 tells us to speak “the truth in love,” it says by doing so we “grow up in all aspects.” This is about maturity — about using discernment and then taking responsibility for our actions.

The box below offers a little help for your discernment process. If you are planning to lie, at minimum, I encourage you to consider trying the steps I offer there first. Let’s be radically honest with ourselves here: How often do our lies deal with thwarting an innocent’s murder or protecting a child’s sense of security? No, usually they’re to protect our own egos.

Have you struggled with whether honesty is always the best policy? What are your experiences in the grey area? Are there harmless lies? What do you think about radical honesty? Comment below.