What do we do with the fact that Anders Behring Breivik — the perpetrator of a terrorist attack in downtown Oslo and the mass murder of children on the nearby island of Utoya — identifies himself as a Christian? How do we make sense of the fact that he refers three times in his “European Declaration of Independence” to the “Lord Jesus Christ”?

1. First, before we say anything else, absolutely the first response of every Christian without exception must be unqualified condemnation of the horrific, disturbing, and profoundly sinful actions Breivik took last Friday. As I’ve written before, on occasion I’ve been frustrated when moderate Muslims fail to condemn acts of terrorism as loudly and unequivocally as possible; yet I understand how Muslims resent that the American public associates them with terrorism and looks to them for a response. The implication is that the moderates are somehow accountable for the actions of the fringe, and it’s incumbent upon them to distance themselves from the madmen who detonate school buses and attack summer camps.

I too resent the implication that I have to offer some sort of account for Breivik’s action. It should be abundantly clear that I have nothing to do with him. And yet – and yet – I do need to condemn his actions. Every Christian does. Every person of good will does. An act of such extraordinary moral monstrosity must, before anything else, be buried beneath an avalanche of condemnation. Christians should always be humbly willing to examine whether a cancer might be growing within their midst, a cancer that is hidden within the body because Christians assume that everyone in their community shares their best intentions. Extremists arise everywhere, and we ought not assume that our ranks are free of them. So let us respond with the moral clarity to call evil evil, and the humility to examine the record and consider whether our actions or inactions, the things we’ve said or left unsaid, could have contributed to the worldview of the madman.

2. Second, we should clarify precisely what kind of “Christian” Anders Breivik is. Because, as it turns out, he’s not much of a Christian at all, at least by ordinary definitions of the term.

Raised in a secular household, Breivik went from “moderately agnostic” to “moderately religious” and was baptized and confirmed in the Norwegian State Church at the age of 15. He is consistently critical of the Catholic Church and the Protestant Church (which he thinks has served its purpose and should reassimilate into the Catholic Church, in order to give a united front against Islam), as he believes both have abdicated their responsibility to defend Christian subjects against an Islamic invasion.

Then, square in the middle of his sprawling 1500-page manifesto, in a section (3.139) entitled “Distinguishing between cultural Christendom and religious Christendom,” Breivik himself tells us what kind of Christian he is. He argues that the inheritors of western Christendom are all, whether they like it or not, cultural Christians. Some are liberal cultural Christians, engaged in a massive act of cultural suicide by facilitating Islam’s demographic conquest of Europe. Others are conservative cultural Christians, such as himself, who have recognized the threat of Islamicization and the infection of a weak and accommodationist “cultural Marxist multi-culturalism” in the elite sphere of European society. Conservative cultural “Christians” should arm themselves for the new Crusade to reassert Christian cultural hegemony and drive the Islamic threat from European lands. As for religious Christians:

If you have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and God then you are a religious Christian. Myself and many more like me do not necessarily have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and God. We do however believe in Christianity as a cultural, social, identity and moral platform. This makes us Christian.

Well, no, actually it doesn’t make you a Christian. Most believers – liberal and conservative alike – decry the notion of “cultural Christendom,” or the theory that a person could be Christian by participating in the outward forms of Christianity while abandoning its inward beliefs, values and relationships. Breivik several times asserts the superior authority of logic and science, and clarifies his commitment to “Christendom” as a monoculture, not “Christianity” as a life of personal devotion to Jesus Christ. Breivik does not see himself as a follower of Jesus Christ, but as a Crusader defending Christendom from Islamicization. He does not defend Christianity as a system of beliefs, stories and existential commitments; he defends Christendom as his own side in the clash of civilizations.

Breivik demonstrates no belief in the deity of Christ, in part because he’s not really sure that there is any God at all. Although he says that those who live “under full surrender with God the Father” will receive his “anointing” for battle, he also says that belief in God is a crutch in the face of death. He writes:

I’m not going to pretend I’m a very religious person as that would be a lie. I’ve always been very pragmatic and influenced by my secular surroundings and environment…Religion is a crutch for many weak people and many embrace religion for self serving reasons as a source for drawing mental strength…Since I am not a hypocrite, I’ll say directly that this is my agenda as well. However, I have not yet felt the need to ask God for strength, yet…But I’m pretty sure I will pray to God as I’m rushing through my city, guns blazing…

Breivik describes how he will be on a steroid rush in the midst of the attack, listening to his iPod (perhaps Clint Mansell’s Lux Aeterna, he says), in order to ward off fear. He explains that he chooses to pray and believe in God in order to overcome the fear of death. He recommends other martyr-crusaders do the same, as religion is “ESSENTIAL in martyrdom operations.”

So, while it was obviously wrong for some commentators to rush to the assumption that this attack in Norway was perpetrated by a Muslim, it is a dramatic mischaracterization to say that it was perpetrated by a “Christian fundamentalist.” He might have been a “cultural Christian” by some definition, and a political fundamentalist, but he was certainly no “fundamentalist Christian.” It’s important to be clear: by almost every definition, Anders Behring Breivik was no Christian at all.

3. Finally, Christians should consider how they can build relationships of mutual respect and understanding across religious boundaries, and should understand the distinction between cultural and religious differences. Breivik is critical of George W. Bush, among others, for saying that our war is not with Islam. Yet Breivik’s atrocity illustrates the wisdom and the importance of this approach. As a matter of fact, there may be a sort of implicit, long-term struggle underway between different cultures and different civilizations, in the way that cultures and civilizations evolve and grow or else fade into obscurity. Yet this is not remotely the same thing as a religious war, and what is emerging may minimize cultural differences and let the truly religious and spiritual differences come through more clearly.

Christianity is not a cultural system. In fact, in those cases where it has become so intertwined with a culture that the two cannot be separated, this is inevitably to the detriment of Christianity. Christianity is fundamentally a relationship with God through Jesus Christ, a community and a way of life, all wrapped up in historical, moral and theological beliefs, values and commitments. These things are not culture and civilization. They shape culture and civilization. They ground and judge culture and civilization, and they can be expressed in a variety of cultures and civilizations. But if we grow committed to the culture and civilization, while the faith and spirituality are hollowed out of them, then we worship empty idols.

All of the western monotheistic traditions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – have violent elements in their sacred texts and histories, bloodstained threads that run through the tapestries of their stories. Christianity and Judaism had largely excised or decisively reinterpreted those elements by the time of the Enlightenment. It’s telling that Breivik had to look back to a medieval order (the Knights Templar) to find a version of Christianity that would arm and equip him for a battle with Islam. But even as we encourage those remaining pockets of extremists within contemporary Islam to reassess and reinterpret the violent threads in its scriptures and stories, we need to make sure that no one else, like Breivik, draws those violent threads out of Christianity and leaves the rest behind. If Breivik had been a “religious Christian,” and not merely a “cultural Christian” who chose to honor the most violent strains of Christendom’s cultural history, it almost certainly would have prevented him from taking the actions he took.

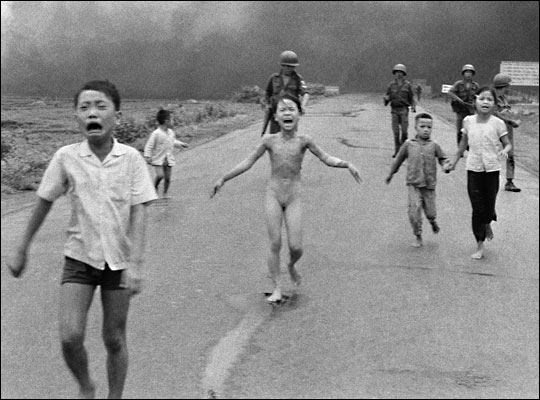

1. BURNED ALIVE TO BORN AGAIN. Many are familiar with this picture, where children and villagers, followed by South Vietnamese soldiers, run down a road after an aerial napalm attack. Her clothes were burned off by fire, and the damage caused by the napalm led her to fourteen months in the hospital and 17 operations. It would have been worse if a soldier, moments after the photograph was taken (one hopes that photographer put the camera down to help), had not given her water and poured water over her body. Few know that the naked girl, immortalized in the Pulitzer-Prize-winning photo, converted to Christianity.

1. BURNED ALIVE TO BORN AGAIN. Many are familiar with this picture, where children and villagers, followed by South Vietnamese soldiers, run down a road after an aerial napalm attack. Her clothes were burned off by fire, and the damage caused by the napalm led her to fourteen months in the hospital and 17 operations. It would have been worse if a soldier, moments after the photograph was taken (one hopes that photographer put the camera down to help), had not given her water and poured water over her body. Few know that the naked girl, immortalized in the Pulitzer-Prize-winning photo, converted to Christianity.