According to the U.S. Department of Justice, 18% of women will be raped at some point during their lifetime. Most victims are acquainted with the perpetrator. The Centers for Disease Control says stranger rapes account for 12.9% that number.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, 18% of women will be raped at some point during their lifetime. Most victims are acquainted with the perpetrator. The Centers for Disease Control says stranger rapes account for 12.9% that number.

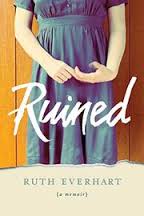

Ruth Everhart and four housemates were held hostage and assaulted by two armed strangers. Her memoir, Ruined (Tyndale, 2016) describes her journey from victim to survivor. She was a college student at Calvin College at the time of the rape, and offers an unflinching narrative about what the crime took from her physically, emotionally, and spiritually:

But if I left this place, where would I go? Who would I be? I was Dutch and Calvinist in the same way I was female – to the bone. How could I walk away from this life? Yet, increasingly, I knew I had lost my place. The world, which had once seemed safe and God-created, was revealed to be full of danger; the church, which had once told me where I belonged in the world, was blind and oblivious and unhelpful. My very body was a liability, a source of pain and vulnerability, a target.

I wanted to love myself, to love my life in a woman’s skin, but that no longer seemed obvious or easy. In fact, what I saw was not only more complicated, it was maddening. For when God created me a woman, God set me up as a target. Set me up.

The insular Dutch Reformed world in which she lived had predictable rules and roles for its members. The rape left Everhart feeling she was an outsider. Her interactions with the police and legal system in the wake of the crime were predictably difficult and dehumanizing, but the alienation caused by no longer fitting into the only community she knew amplified the trauma. She struggles to finish school while walking around campus feeling like a marked woman. Her friendships with the other housemates who were also assaulted that night were both a source of solace and a constant reminder of what each had experienced. Her own sense of being silenced and marginalized as a result of her experience grew to encompass what she saw as systemic silencing of women in the church of her childhood. Her sense of physical well-being was entirely stripped from her. If a couple of armed men could break into an apartment and spend hours raping its residents, where could she ever feel safe again?

As time went on, Everhart sought answers in a destructive relationship with a married seminary student, then by relocating to a new city. Her narrative is a reminder that the road from victim to survivor is not paved. In fact, it is not even clearly marked. She offers readers a great deal of detail about each step of her journey during these first few years. Some readers may find this level of detail slow going, but that’s precisely the point. Reclaiming a new normal after a rape is slow going.

Time doesn’t heal all wounds. Everhart’s life was sent on a different trajectory because of the rape. She eventually meets a man she can trust, which is, at its heart, is a pretty good working definition of love. She eventually finds her way to seminary, where she reclaims a more mature version of her childhood faith. And as she gives birth to her first child, she finds a measure of shalom, of wholeness. Her body was once an object of violence. Childbirth was at once a proclamation of her agency over her own body as well as an expression of hope in its creator.

A social worker once told me it is hard for grief to hit a moving target; Ruined offers readers an unflinching look at what it means to become a moving target in search of sanctuary from trauma.

Note: I received a comp copy of this book from the publisher.