Muslim History Detective’s log, 08/7/13

TALIB SHAREEF, a retired U.S. Air Force veteran and imam of Washington, DC’s Masjid Muhammad, eloquently delivered the opening prayer during last Wednesday’s session of the U.S. House of Representatives. What a refreshing sight to behold during the final few days of the blessed month of Ramadan.

TALIB SHAREEF, a retired U.S. Air Force veteran and imam of Washington, DC’s Masjid Muhammad, eloquently delivered the opening prayer during last Wednesday’s session of the U.S. House of Representatives. What a refreshing sight to behold during the final few days of the blessed month of Ramadan.

At one point, the Muslim leader spoke of the “many diverse, wonderful, beautiful expressions of human life that have contributed to the beauty and strength of America.”

When I heard those words, I could not help but think about the Africans of Muslims heritage among the precious human beings who were enslaved on American soil. They, too, had contributed to the making of America, their sacrifices crossing three centuries no less.

And when Congressman Keith Ellison, also an African-American and the first Muslim ever to be elected to the U.S. Congress, read the imam’s bio shortly thereafter, I could not help but think about the irony of the whole beautiful scene.

Here stood two powerful African-American Muslim men, representing the community-building essence of Islam. And they were doing it in a place where their religious forefathers, in bondage in America, could never have dreamed would be possible. Even more profound is the fact that members of Congress, lawmakers who had once stood in that very same room, owned Muslims slaves. Surely Imam Shareef grasped the deeper significance of the moment also, especially given his position as an advisor to America’s Islamic Heritage Museum.

After watching the prayer on C-SPAN, I came across a 2011 Voice of America article titled “For African-American Muslims, Ramadan Has Special Meaning.” Therein, Imam Shareef makes connections between Ramadan, African-Americans’ struggle for justice post-slavery and why many of those African-Americans embraced Islam:

“Imam Shareef says there is a strong connection between African-Americans’ historic struggle for freedom and equality since the end of slavery in the 1860s, and the Islamic tradition of seeking spiritual freedom. Ramadan, he says, is a chance for Black Muslims in America to remember that.”

“You know, we’re coming out of slavery,” Shareef explained. “So that was a journey to see humanity free. And becoming Muslims through that experience it was highlighting three particular words – freedom, justice and equality. That’s what we wanted. And every human being wants that.”

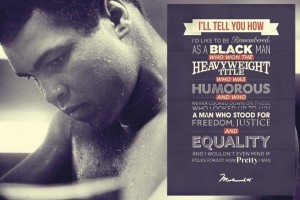

What is so compelling about the African-American connection to Islam is twofold: One, the stories of enslaved Muslims of black African descent remain the most visible traces of early American Muslim life and history. And, two, African-American Muslims who passionately fought for freedom, justice and equality, post-slavery, remain the most recognizable Muslim names—to all Americans—in American Muslim history today: Imam W.D. Mohammed, Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz), to name a few. Ali once stated:

“I’ll tell you how I’d like to be remembered: as a black man who won the heavyweight title, who was humorous and treated everyone right, as a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him, a man who stood for freedom, justice, and equality, and I wouldn’t even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was.”

It should come as no surprise then that the first and only Muslims to have ever been elected to the United States Congress are African-Americans, Congressmen Keith Ellison and André Carson. They are inheritors of a uniquely American legacy of intense, sustained struggle for freedom across diverse communities, for the betterment of humanity.

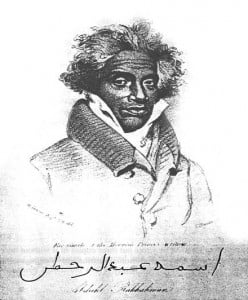

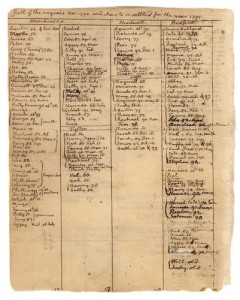

As we, American Muslims of diverse races and ethnicities, freely and comfortably practice our faith this Ramadan, it would do us some good to reflect on what religious life was like for some of the earliest Muslims in this land. One example to look at is the life Bilali Muhammad, a West African-born Muslim enslaved in nineteenth-century Georgia. He arrived on future Congressman Thomas Spalding’s Sapelo Island plantation sometime around 1802. Spalding not only owned hundreds of slaves but he was also a leading scientific agriculturist and an American statesman. His influence as an agriculturist could not have been possible without the his slaves’ great labor and knowledge in this science. His political resume included the Georgia State House of Representatives (1794), the Georgia State Constitutional Convention (1798), the Georgia Senate (1799), and the U.S. House of Representatives (1805-1806). He even presided as chairman over the Georgia Convention of 1850. Convention attendees resolved that the state of Georgia “will and ought to resist even (as a last resort,) to a disruption of every tie which binds her to the Union, any action of Congress upon the subject of slavery.” And this, of course, meant anything that might negatively affect the slave-holding states, including attempts to abolish slavery.

In the same year that Bilali arrived in Georgia, President Thomas Jefferson attended church services held in the U.S. Capitol in the House of Representatives. This marked his first church appearance during his presidency. Evangelist Baptist John Leland delivered the sermon that Sunday in 1802. The same John Leland who had fought hard to ensure that even Muslims (yes, he specifically named them) would be able to enjoy the full protections of religious freedom, including holding “any office in the government, without any religious test, to make them hypocrites.” Two days before the Capitol church service, President Jefferson received Leland at the White House, where the Baptist leader lauded Jefferson’s support for the “prohibition of religious tests to prevent all hierarchy.” Later that day, Jefferson penned the now famous letter to the Danbury Connecticut Baptist Association assuring them “religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship.”

These are truly beautiful words except we cannot forget the contradiction: Jefferson owned hundreds of human beings who could not enjoy the full rights of citizenship on account of them being slaves. They did not have equal access to (quality) life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness—unrestricted by their status as property—let alone the opportunity to experience, fully, the beauty of religious freedom. How can one be free to worship fully, according to one’s own conscience, if one is not free to move about the land in expression and full development of that worship? Jefferson could choose when, where and how he wanted to worship. Could all of the slaves do the same? No. In 1802, while Americans of diverse faiths were still settling into (and evolving the expression of) their religious freedom, the slaves were at the mercy of whatever their respective owners would allow, as well as laws that regulated slave activity.

We may never know if Bilali arrived on Spalding’s plantation before or after the commencement of Ramadan that year. We do know the blessed month began just five days after the Sunday Leland preached at the Capitol. If Bilali did arrive during Ramadan, was he able to observe all the rites of the blessed month given his situation as a captive servant? One can only wonder.

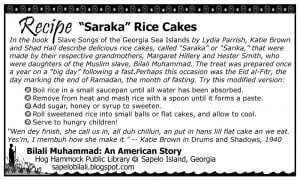

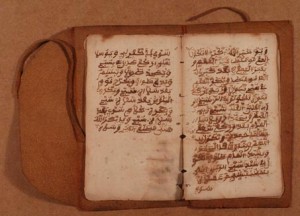

What is clear about Bilali is that he was a devout Muslim. In his book The Seed that was Sown in the Colony of Georgia, Spalding’s grandson, Charles Spalding Wylly, recounted that Bilali “faced the East and called upon Allah” during his prayers, and he often recorded plantation events in Arabic. Caretakers even buried Bilali with his Qur’an and prayer rug when he died. Given all this, I cannot imagine Bilali would have willingly given up the obligatory, daily, dawn to sunset fast during Ramadan. Scholars like Sylviane Diouf agree, details of which can be found in her book Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. After all, Bilali even sought to keep up with his Islamic scholarship. He authored a 13-page Arabic manuscript, sometimes referred to as the “Bilali diary.” It is rare, according to the late historian Bradford G. Martin, in that it remains “one of a very small group of original Arabic manuscripts discovered and preserved in the United States.” The word “diary” is a misnomer though, as the text discusses various forms of Islamic worship and ritual preparations, as well as draws from Islamic jurisprudence. In Sapelo’s People: A Long Walk into Freedom, William S. McFeely, a Pulitzer Prize winning professor of history, who also helped create Yale’s African-American studies program during the Civil Rights Movement, described Bilali’s manuscript as “an icon, in the true sense—a holy object connecting Africa to America in the hand of a deeply religious man.”

That connection is documented in diverse ways. The award-winning film Daughters of the Dust, Toni Morrison’s award-winning book Song of Solomon and proceedings of Savannah unit of the Federal Writers’ Project, to name a few, all contain traces of Bilali’s life and experiences. In 1829, slave trader Zephaniah Kingsley described as “remarkable” the actions Bilali and another Muslim took to protect their respective owners’ interests during the War of 1812. Kingsley also referred to the two men as “influential negroes,” “Africans,” and “professors of the Mahomedan religion.” Herein lies yet another ironic point: These Muslim men stepped up to protect American independence all the while knowing that they would never again be free.

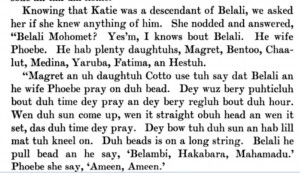

Surprising as it may be to most, Bilali was the leader of as many as 80 “devout” Muslims on the Spalding plantation, including his wife and nearly 20 children. It is compelling that the head of one of the earliest documented Muslim communities in America was a West African-born Muslim. In her book God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man, Bilali descendant Cornelia Walker Bailey explained that the Muslim leader’s Sapelo descendants blended many of his Islamic practices into their religious practices upon becoming Christian. This included never entering the church before cleaning one’s feet. (Muslims remove their shoes before entering the prayer area of the masjid.) The church congregation also separated by gender during services, men on one side and women on the other. (For congregational worship services and prayer, Muslims traditionally separate by gender, men are in the front rows and women are in the back rows.) And there were also some similarities in the direction of prayer, ablution before prayer, the direction of body placement in the grave upon burial, and so on. Bailey’s last name is even derived from her ancestor’s Muslim name: Bilali.

This is history that all Americans should know: Muslim life, lived on American soil, is just as quintessentially American as that of any founding father. Muslims were here contributing to American life and advancement even before the births of the principal author of the Declaration of Independence (Thomas Jefferson), the Father of Our Country (George Washington), and the Father of the Constitution (James Madison). One such example is Job Ben Solomon (Ayuba Suleiman Diallo), an African-born Muslim and imam. Held captive in colonial Maryland, he ran away from a plantation there sometime between 1730 and 1731. And why did Job run? Partially because he wanted freedom, of course, and partially because he could not pray his obligatory Islamic prayers in peace.

Job eventually gained his freedom and returned to his homeland but not before having an impact on colonial America. You see the African imam could read and write Arabic fluently. He even had the ability to write entire copies of the Qur’an from memory. After Job ran away, the authorities eventually caught him and returned him to his owner. Recognizing Job’s intellectual acuity, the slaveholder allowed Job to write a letter, in Arabic, to his father back home. The letter never reached the elder, in what is now Senegal, but it did come to the attention of James Edward Oglethorpe, the future founder of colonial Georgia. Oglethorpe took action to help facilitate the Muslim’s freedom and eventual return home by way of England. This is compelling because Oglethorpe had participated heavily in the slave trade business but seems to have left it all behind shortly after aiding Job. In fact, according to some accounts, it is his encounter with Job’s compelling story that influenced him to ban slavery in Georgia from the outset, refusing “to make a law permitting such a horrid crime.”

That is right, in the same state where Bilali later spent the rest of his life as a slave—on the plantation of a man who had served in the United States Congress and had been part of a community willing to break ties to the Union to preserve slavery—slavery had originally been banned. And it had not been banned by just any man. Slavery had been stopped cold in Georgia, before it could start, by its founder, a man who had helped free another Muslim slave a century earlier!

Ramadan for Bilali, while in bondage, came and went for more than half a century on the Spalding plantation. He did not get to return home like Job. Given his dedication to Islam, I pray he was able to observe this religious obligation in a way that truly fulfilled him spiritually. Most likely he did, given the community he had around him. However, his situation should be considered an exception, not the rule.

We, American Muslims today, so freely move about this land, practicing our faith without a second thought. During Ramadan, we enjoy the freedom to offer up extra prayers through the night. We travel from house to house and masjid to masjid to break our fast and worship with community members. And at the end of the hallowed season, we celebrate, dressed in our very best clothes, sometimes with thousands of other Muslims in our respective local communities. Given the restrictions on their time and movement, what did the majority of Muslim slaves in America have during this blessed month? Not many were as fortunate as Bilali and even that situation had its limits.

We must never forget those “beautiful expressions of human life”—Muslim men, women and children among them—that, early on, contributed to the making of this nation. The way I see it, Muslims’ prayerful presence in the U.S. House of Representatives on July 31, 2013, was as much about our community-building efforts of today as it was about honoring the sacrifices, in years gone by, of our Muslim forebears in America. I am confident that the congressman and the imam would agree.

***

For additional reading, download a copy of my paper “Muslims and the Making of America,” published by the Muslim Public Affairs Council in February 2013.