By Precious Rasheeda Muhammad and Guest Co-Author Mahasin Abuwi Aleem*

We read a well-meaning article recently, by Chaplain Bilal Ansari, which misrepresented the history of the American Muslim community that once referred to themselves as “Bilalians.” We co-authored this piece to correct the most problematic inaccuracies. Going forward, we will also be co-curating a documentary website, The Bilalian Project, to provide a window into how this rich history fits in the greater narrative of Islamic, African American, and United States history. We are thankful to the chaplain for starting the conversation.

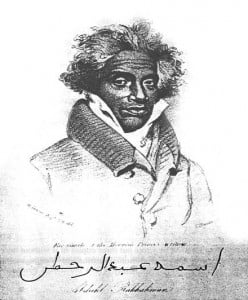

From the mid-1970s to the early ‘80s, the community of Imam Warith Deen Mohammed identified themselves as Bilalians, a name derived from the historical figure Bilal ibn Rabah, the Abyssinian slave who lived during the time of the Prophet Muhammad. Bilal heard the message of Islam and would not let it go, even under intense pressure and physical torture from his slave owner. Emancipated through the intercessions of Muslims, he became one of the most significant figures in Islamic history, a close companion of the Prophet Muhammad, and the first to call and perfect the melodious, Islamic call to prayer –adhan – called by Muslims throughout the world five times a day.

First introduced to his community as early as November 1975, Imam Mohammed’s use of the term “Bilalian” was designed to free the minds of a people; to move beyond the trappings and limitations of colorism and racism; to enable them to see themselves as slave servants of God alone; to follow the moral arc of Bilal ibn Rabah; to be truly free.

Throughout the years of his leadership, Imam Mohammed defined exactly what it meant for one to be free. He once explained:

“Freedom is to move in our intellect to a greater vision, a greater purpose, to a greater responsibility until we are comfortable with ourselves in our life and in our purpose on this earth. Until that happens we will continue to be a burdened and confused people. It’s a natural requirement [for] the life of every human being that their intellect be liberated.”

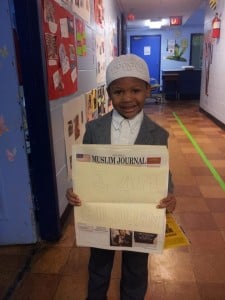

The imam’s teachings on Bilal are well-documented in a number of mediums, including in his community’s own newspaper of record, the Muslim Journal (which underwent several name changes, including being called Bilalian News); in our nation’s newspaper of record, the New York Times; and in the 2002 film Bilalian, which had a special showing at Harvard University in 2003.

On May 25, 1978, the New York Times got it right when it reported on the imam’s use of the term Bilalian instead of black, as part of rejecting the designations of “black” and “white” as limiting terms that harken the mind back to racist ideologies.

A 1981 interview with Imam Mohammed, in his community’s paper, gives us further insight on this thinking:

“Actually, I do identify with black: that is, with black Africa, with people of African descent; it’s impossible for us of African descent not to identify with blacks in that sense. However, I have found in my discussions with Muslims and non-Muslims that they share my sense of need for a term that is richer in meaning than the term ‘black.’”

In 1976, Imam Mohammed described the Bilalian community in the following way:

“The Bilalian community of the West is blessed by Allah with the knowledge of divine truth that can lead the entire world to peace and accord with the Creator. We are a people who, like Joseph’s coat of many colors, represents all of the people of the world. The Bible story of Joseph’s coat (Genesis 37th Chapter) says that the coat was desired by all of Joseph’s elder brothers, but Joseph’s father chose to give the coat to Joseph, who was the youngest of the brothers. We as a people in America are the youngest of all people on the earth. We have been called “Negroes” and other names, but we now have a new name, “Bilalians,” which fits us much better. It is just now that we are beginning to recognize ourselves and we are getting the world to recognize us as a separate and unique ethnic people.

Ethnic means that we have our own history as a people. It is said that we began our history in so-called Africa, but we did not begin there. Our history as a people began when Islam came to us and gave us life because we had been reduced to nothing. The Bilalian people of the West represent all of the people on the face of the earth in our physical features and in our complexions.”

Finding a dignified term to capture the dynamic history of those of African descent on U.S. soil has been pursued by a number of African-American thinkers, including renowned Harvard scientist, and founding Director of the Harvard Foundation, Dr. Allen S. Counter.

In a January 25, 1989, letter to the New York Times, nearly twenty years after Imam Mohammed pioneered the term “Bilalian,” Dr. Counter put forth his own suggestions for a way to address the problem with proper “identification and labeling” of “black Americans”:

“In our search for a positive identity of our own choosing, we have gone from African, to colored, to Negro, to black (a protest term that demonstrated we preferred to identify with our African rather than our European-American past).

While the term African-American does represent an advance in the continual evolution toward a true identity for a people whose ancestors were forcibly brought to this hemisphere by Europeans, forcibly held in slave labor and forcibly mixed in racial composition, it may be imprecise, or equivocal at best.

Genetically, almost all of today’s ”black Americans” are a racial mixture of African, American Indian and European bloodlines. Regardless of skin color, we are a genetic creation of this hemisphere, and America is our only home. Perhaps the name Afrindeur-American would be more precise.”

Dr. Counter’s reasoning was not far off from that of Imam Mohammed’s when the professor spoke of America being “our only home,” of black Americans being a new people, needing a new name, “regardless of skin color.”

Imam Mohammed, however, had taken the search for a name a step further, beyond just race.

The decision to use the name Bilalian took Imam Mohammed’s community members from racial beings to spiritual beings. Over time, he thought the term might even catch on in use with the greater black American community.

His exact words in fall 1975:

“Because of the great dissatisfaction and confusion among our people concerning a proper and dignified name for themselves, we are very happy to make the following announcement to all so-called Black communities in the West:

EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY, I CHOOSE TO CALL MYSELF A “BILALIAN,” AND I INVITE ALL OF YOU TO TAKE ON THE SAME NAME.”

Imam Mohammed once described Bilal as a soul whose deeper human sensitivity made him at peace in the most difficult of circumstances, even as a slave, and that peaceful consciousness allowed him to turn unyieldingly to God alone when the time came.

In speaking about the Bilalian community, Imam Mohammed said in 1976:

“Now, today, we are here with a new consciousness that is not a black consciousness or a white consciousness but a divine consciousness.”

The focus was not on Bilal the man.

The focus was on Bilal the mind.

He further explained:

“The Lost – Found Nation of Islam is not looking for an ideology or a philosophy to solve the problems of the Bilalian community and the world – we have the solution. Our number one idea is the truth and the reality of Almighty Allah, the One God Who made the heavens and the earth. Our second idea is the revelation that Allah has the power to reach His servants with divine guidance in the way of divine books or revelations.

Our “ideology” is Islam as it is spelled out in the Holy Quran and our “philosophy” is freedom, justice, equality: Islam.”

Criticism and misunderstanding from the greater Muslim community eventually led to Imam Mohammed dropping any official use of the name Bilalian for his community. In a 1993 interview with Dr. Edward E. Curtis (then a graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis), the imam explained:

“We were charged with a division in Islam, of making Bilal our leader rather than the Prophet.”

No matter their faith tradition, black Americans in general were still searching for a dignified name during those days. That Imam Mohammed chose Bilalian should be seen in that context, not as some creation of a new division of Islam cut off from a greater understanding and respect of the Islamic faith tradition.

During one of his community’s C.R.A.I.D. (Committee for the Removal of All Images that attempt to portray Divine) meetings in 1980, Imam Mohammed made the case that the Bilalians, like the historical Bilal, would be the ones to “declare the Shahadah from the top of the house, openly to all people.”

He proclaimed that they would have enough spirit, courage, devotion, will, and “love for all God’s people to stand on top of the house and tell the whole world that `there is nothing worthy of worship except Allah [God]; Muhammad is the universal Messenger.’”

“They will stand on top of the house. They will let their light shine, they won’t be afraid and they won’t hoard the knowledge,” he declared to all present.

C.R.A.I.D., which courageously reached out to and gained support from other faith communities, is but one example of Bilalians taking to the top of the house and calling out to humanity.

It is unfortunate that so many amongst the greater Muslim community got the meaning behind the use of the name Bilalian so wrong.

Many are still getting it wrong today.

Which brings us to the inspiration for our article.

When Chaplain Bilal Ansari refers to Bilal, in his February 21, 2014, article on The Huffington Post, as having been the only “star” Imam Mohammed’s community could see, and the “imminent guiding star” of the community once called Bilalian, he not only gets history incorrect – history that is clearly spelled out in the historical record – it seems that he is making the same charge of which Imam Mohammed was unjustly accused, albeit unintentionally.

Within hours of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad’s passing in 1975, Imam Mohammed, son and successor, held up a Holy Qur’an and told a room full of hundreds of the community’s leaders:

“We have to take this down from the shelf. We say we are Muslims. What my father taught that is in this book, we will keep. What is not in this book, we have to give up.”

From day one of taking over as leader of the Nation of Islam, and beginning the process of transitioning the community to orthodox Islam, Imam Mohammed had a laser focus on promoting God consciousness, working together with all good people for the betterment of humanity, and broadening his community’s knowledge of Islam.

It is through a clear Islamic filter that his teachings on Bilal, and his unyielding continuing commitment – set forth in the Nation of Islam – to elevating the self-worth of those of African descent in America, flowed.

Imam Mohammed did not stall progress in exchange for stability. He immediately took up the mantle of liberating the mind.

So the respected chaplain misinterprets the history lesson when he juxtaposes Imam Mohammed (one of his teachers) with the well-respected Imam Zaid Shakir (also one of his teachers), asserting that the former “used [Bilal’s] light as source of community stabilization” and the latter used “his light as a means of mobilization toward liberation.”

But from where does the misunderstanding derive?

Why does the mistaken narrative persist that Imam Mohammed could only understand Bilal’s existence in some limited way?

It derives from an unfortunate leitmotif that Imam Mohammed, and, by extension, his community, were limited in their understanding because they did not have exposure to “traditional” (read: authentic) Islamic learning.

The chaplain writes:

“My other teacher, Imam Zaid Shakir, recognizes the brilliance of Bilal ibn Rabah by placing him as one among a constellation of many bright stars of the companions of the Prophet Muhammad. Imam Zaid, due to access to traditional scholars in Damascus (where Bilal ibn Rabah is buried), unlike Imam Mohammed, had the privilege of being able to see more of the night sky despite the glow, glare and clutter of the urban sky. To Imam Zaid, to stay narrowly focused on one star despite its brilliance was limiting. ”

Let us make it plain.

Imam Mohammed did not come up with the term Bilalian due to limited Islamic knowledge. Members of the community of Imam Mohammed had access to “traditional scholars” – and scholarship – throughout the community’s history, some of whom came from abroad to teach amongst the community in the United States, some of whom already existed amongst the community, even prior to Imam Mohammed assuming leadership in 1975.

Additionally, during Imam Mohammed’s three-plus decades as leader of the community, he also sent delegations of his students, men and women from cities across the United States, to several majority-Muslim countries to study Arabic and the Islamic sciences, including those who studied at Abu Nour University with the late Grand Mufti of Syria, Shaykh Ahmed Kuftaro, with whom Imam Mohammed himself had a close relationship.

Just because a community chooses an independent path in some respects does not mean that other paths are alien to them, nor does it mean that they are ignorant of those paths, nor does it mean they have not been exposed to them.

A community with the mind of the Bilalian community (as Imam Mohammed used to say, “man means mind”) could never focus on just one “star”, not even in their most challenging times. Recall that Imam Mohammed was already busy liberating the community leaders from any teachings that contradicted the Qur’an just hours after his father’s passing, which was an exhaustively devastating time for the community. And yet, in that moment, the imam, upon becoming the new leader of the Nation of Islam, had fearlessly chosen liberation of the intellect over stability of the moment.

No “glow, glare and clutter of the urban sky” was going stop him, nor did it ever.

Ultimately, Chaplain Ansari’s imagery is compelling but it is just not historically accurate, although we accept that this is his understanding:

“In the absence of a complete visible night sky, Bilal ibn Rabah became the imminent guiding star in a community called the Bilalians, formed under the leadership of Imam Warrith Deen Mohammed in the late 70’s and early 80’s in the United States.

Although the global community identified as Muslims, Imam Mohammed at the time understood the urgency and agency in stabilizing our identity and traumatized mental state under Like the light pollution that incapacitates our ability to see far and beyond when we attempt to gaze at the heavens today, Imam Mohammed’s community could only see Bilal ibn Rabah – a Black slave turned hero – when they looked at the Prophet Muhammad’s companions. Perhaps Imam Mohammed knew that in our vulnerability as a community, we risked losing our identity as African American Muslims if we did not follow a brilliantly familiar star.”

Litmus tests for who is really qualified to speak for Islam, or even to fully understand it, have historically only served to alienate various segments of the American Muslim community from each other, and only allows for cursory and superficial engagement with some of the community’s leaders and thinkers. The community of Imam Mohammed has often been subjected to this treatment.

The reality is that the historical record does not support the chaplain’s assertion that the community was so mired in transition that they were handicapped from seeing the brilliance of the greater Islamic narrative beyond one individual, “a Black slave turned hero.”

To make the case that the community “could only see” Bilal ibn Rabah is to misunderstand the message.

There was no myopic focus on Bilal to the exclusion of the life of the Prophet Muhammad, including the role of his companions in it.

The community was not “depending” on one star to get them to the “promise land” as the chaplain alludes.

No, they were identifying with a mindset they needed to be in along the way, a mindset that opened them up to the whole universe of Islam not just one “brilliantly familiar star.”

And yet, Chaplain Ansari, juxtaposing Imam Mohammed’s teachings with Imam Zaid’s, opines:

“Thus, Imam Zaid Shakir in the rich Black History narrative chose to describe and articulate the way to sobriety and moral excellence through intimacy with the broader night sky.”

It is precisely because of Imam Mohammed’s engagement with the “broader night sky” that his thinking was before its time, even years before Imam Zaid would become Muslim in the late 1970s, and in that regard should be studied more carefully and placed more thoughtfully not just within the “rich Black History narrative” but within the greater history of America and the greater history of Islam.

It is an injustice, no matter how unintended, to the legacy of Imam Mohammed and his community to constantly misrepresent this history.

Imam Mohammed’s “imminent guiding star” was always Muhammad the prophet’s life example.

His greatest guidance was always the Qur’an.

The term “Bilalian,” and his teaching about Bilal ibn Rabah, were just one aspect of his strategy to get his community closer to them both.

*About the Guest Co-Author: Mahasin Abuwi Aleem, a graduate of Brown University with a major in Political Science, was part of a delegation of students sent by Imam Mohammed to study at Abu Nour University’s dawah college in Damascus, Syria at the personal invitation of then Grand Mufti Shaykh Ahmed Kuftaro. A future archivist and librarian, she will begin studies for a Masters in Library and Information Science in August 2014.

**We reached out to Chaplain Bilal Ansari and the respected Chaplain has graciously agreed to post an excerpt of our article and a link to it on his Huffington Post blog, possibly for his Jummah post. We will post the link here when it is available, Insha’Allah.