By Joshua Sharf.

Over the last 50 years, the success of Israel, America’s movement toward a more open society, and a desire for a closer relationship between Christians and Jews, have led American Christians to begin to confront the Christian roots of anti-Semitism in a serious way.

The reorientation really began in late 1965, with Pope John XXIII’s Nostra Aetate, where he disavowed Jewish responsibility for the crucifixion and acknowledged the continuance of God’s covenant with the Jews, a statement reinforced by Pope John Paul II in November 1980. It was affirmed by Israel’s stunning victory in 1967’s Six Day War, which showed the world Jews who fight. If there’s anything Americans respect, it’s people who fight for themselves.

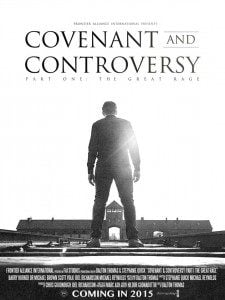

Now a new movie, Covenant and Controversy, takes on replacement theology, or supersessionism, with mixed results. Still preached by many evangelical faiths, replacement theology has been responsible for some of the deepest anti-Semitic attitudes in Europe and what used to be known as Christendom.

Simply explained, it is the claim that the Christian church has replaced, or superseded, God’s covenant with Israel, and that God’s special relationship with the Jews has been terminated.

For obvious reasons, such a view is in direct opposition to Judaism. In a live-and-let-live environment, that wouldn’t matter so much. However, it has also historically led to contempt, forcible attempts at conversion, and violent reprisals when such attempts were rebuffed.

Even in the United States, supersessionism was a mainstay belief of the Southern Baptist Convention. Eli Evans, in his history of the southern Jewish experience, The Provincials, helps describe the bifurcated relationship that he and his fellow Jews had with their largely Baptist neighbors, and supersessionism’s contribution to it. Jews were the living embodiment of the Old Testament. But they were also derided for having missed the New Testament boat, and considered prime targets for conversion.

Now, there is a push among some evangelical groups to renounce replacement theology as disrespectful to Judaism, dangerous to Jews, and destructive of the Jewish-Christian relationship.

The movie’s imagery is fairly simple – mostly archival footage from World War II and Israel, along with talking heads. It’s the seriousness of the topic, and the sincerity of the speakers, that hold one’s attention.

While the Nazis were not Christian, Covenant and Controversy insists that their genocidal plan only found a receptive audience through centuries of preparation by Christian anti-Semitism, even though Christianity itself never countenanced the wholesale murder of Jews. The film doesn’t merely concede the point; it makes it one of the pillars of its argument.

It also looks to current Muslim anti-Semitism as it relates to Israel, recognizing both the unique nature of Muslim Jew-hatred, and also some of the themes that Arabs have adopted from Christian Europe.

The film seems to be a sincere effort on the part of evangelical Christians to take ownership of Christian anti-Semitism, and try to root it out of Christian practice.

The leading subject of the movie, Dalton Thomas, explicitly says that anti-Semitism is a result of the missionary effort, and that:

If your theology of Israel divests them of their national, ethnic or territorial, identity or destiny, you have embraced replacement theology…. Namely, that there are no promises that remain for the Jewish people on a national level.

Still, those looking for a renouncement of missionizing to Jews will be disappointed.

One woman attributes Jewish rejection of Christianity not to irreconcilable theological differences, but to past Christian persecutions, hoping that turning a new page on that will lead Jews to be more receptive.

When the honey-rather-than-vinegar approach fails, as all other approaches have failed, one can imagine deep disappointment resurfacing as outright resentment.

Others acknowledge the past, but seem determined to repeat the mistakes that helped lead to it. “The Jews have suffered, and there’s more suffering to come. I think, frankly, the worst is yet to come. And Christ then will return and then all Israel will be saved. Therefore, today, even in spite of the Holocaust, the Jew needs to hear the Gospel. The Christian needs to hear the Gospel.”

Christianity remains evangelical, but the need specifically to convert Jews is dangerous, and profoundly anti-Semitic, as Thomas’s comments make clear. At first glance, the equating of Christians and Jews in the above quote might seem likee progress in that regard. In practice, people’s limited capacity for self-appraisal being what it is, it can lead Christians to favor proselytizing to Jews who are obviously not saved.

The asymmetry in this approach should be obvious. There are 2.2 billion Christians in the world. Jews number less than one percent of that total, using the most generous measurements.

Jewish participation in an intramural Christian theological debate must necessarily be limited. Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, in his legendary essay, “Confrontation,” notes the dangers of interfaith dialogue, in particular, the dangers of attempting to reconcile core beliefs of different faiths. The obvious danger is that such requests will be reciprocal. If we ask Christians to edit their beliefs, what then will they ask of us? Critically, erasing the differences between faiths erodes what is unique about each faith community.

Jews do, however, have the right to ask Christians to refrain from past aggressive tactics. When the Mormon Church opened a center in Israel, the government made it a condition that they not proselytize. Israel couldn’t very well ask them not to take walk-in business, but advertising and marketing campaigns were another matter. Such enforcement would be unthinkable absent a Jewish state, but virtually no Christians oppose it.

The unresolved tension among the different viewpoints should leave Jewish viewers uncomfortable. We rightly have no input to the debate, but we have a very definite stake in its outcome. Perhaps the most hopeful and unprecedented development is that the discussion is happening at all.

We can take heart that Christians increasingly take Thomas’s approach. When I asked a friend of mine, she hadn’t heard about replacement theology at all. “Transferred? No way. Gentiles were grafted into the original tree of life, but we do not replace it and it was not transferred. God decides who is accepted into Heaven. He is the one who knows our hearts.”

Joshua Sharf is a Fellow with the Haym Salomon Center and head of the PERA project at the Independence Institute. Follow him @joshuasharf.