Connor Wood

I grew up in a very creative, artistic family. My mother was a former fashion illustrator and model, while my stepfather was a handy musician who kept our house full of dulcimers, guitars, and wooden Irish drums. All the kids became musicians. In my adolescence, though, I grew frustrated by the fact that many other families seemed far less artistic and excited than us, but way more stable and collected. Why couldn’t we have both at the same time? Part of the answer, I think, has to do with religion. Being religious is correlated with personal happiness and satisfaction with relationships – but anti-correlated with openness to new experience and, by implication, creativity. Is it possible to somehow get the best of both worlds?

Creativity is a dangerous and wonderful thing. But it’s not always compatible with religion, or stability. Let me explain why. First, imagine a fashionable young woman walking down the street. Say, a descendent of Ernest Hemingway. She’s cool, right? And she’s creative. The amount of energy and thought she’s put into her appearance is impressive, and it’s paid off – she doesn’t just look good; she looks fascinating.

Importantly, her crackling, cutting-edge, creative “cool” is characterized by newness – you can’t wear the same clothes* as last year and call yourself creative.

Now, imagine that same young woman in front of a church congregation, leading a worship service. Would she look as fashionable? Would her appearance have the same “edge” to it, the same keen savvy? Almost certainly, the answer is no. She would be dressed more conservatively. The same goes for the rest of the congregation – church attire is often respectable, but rarely creative. (There are exceptions: Protestant woman can sometimes wear shockingly ornate hats.)

This isn’t just my subjective opinion, either. Take a look at this quote from a fascinating study on creativity and conservatism, which anonymously judged subjects’ photo essays and drawings. The authors found that more conservative people “had fewer creative accomplishments and devised photo essays and drawings judged as less creative.” They also discovered that

among conservatives, religiosity was a common theme. Religiosity was expressed in photos and comments about preparing for the ministry, inspirational quotes, photos of the Bible, a photo of participant and her young daughter dressed for church, and references to family values.…Just one conservative participant made reference to creativity (i.e., poetry).

Compare this with the study’s more liberal subjects, who were generally less religious, but more creative:

Four made reference to boundary-crossing …including two who depicted use of illegal drugs, one woman showing herself dating a man of a different race, and another student with his car “parking over the line,” taken to portray his disdain for rules.

But why is this? Why shouldn’t religious people also be creative people? Why can’t church be a place to express outrageous individuality, to be artistic? Why do we have to give up the stability to get creativity?

Research tells us that religions are, in many ways, tools for uniting individuals into collectives. They use rhythmic motion during rituals to synch up people’s bodies, making them more trusting of and willing to sacrifice for one another. They use peer pressure and in-group reputation to ensure that people stay in line. And they’re replete with myths, symbols, gods, and stories that inspire people to act in accordance with the group’s norms and act cooperatively. Like it or not, religion is social glue.

And this isn’t a bad thing. Without the ritual and social tools religion offers, it would be much more difficult to unite people into the small-scale, personal groups that conservative philosopher Edmund Burke called the “little platoons” of society. And in the absence of such groups, social fabric starts to degrade pretty quickly – as the Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam has spent the past decade and a half politely trying to tell us.

Now, I’m just an amateur compared to Putnam, but I’m publicly stating here that he’s right.†

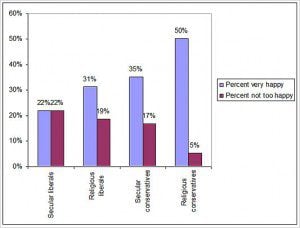

The data are clear: religious people are happier with their relationships, more likely to be married (which itself seems to make people happier), more likely to have children, more satisfied with life, more generous with charities (including secular ones), and less likely to get depressed or attempt suicide than secular folks. In other words, they’re more stable.

But here’s the thing: fulfilling all of a religion’s requirements, from attending its services or learning its rituals to organizing the Saturday potluck, takes energy. Like, a lot of it. And the more energy you put into the everyday minutiae of group life, the less energy you have to explore new horizons.

Even more importantly, group life demands shared systems of meaning. It’s like language, which only works when people agree on the meanings of words. If “watermelon” means “large, juicy fruit with irritating seeds” to me, but “a small species of hairless vole” to you, we are going to run into some very interesting problems when planning our picnic. Communication, in other words, depends on everyone seeing things in mostly the same, established ways. But creativity is about seeing things in new ways – inventing new meanings and unfamiliar symbols. This may explain the findings of Open University of Israel researcher Sonia Roccas, who recently determined that religious people

attribute relatively high importance to values expressing motivation to avoid uncertainty and change…and relatively low importance to values expressing motivations to follow one’s hedonistic desires, or to be independent in thought and action.

So it seems that creativity and group life are a zero-sum game: in order to get more of the one, you have to give up some of the other. The more invested in religious life you are, the more you’re going to care about preserving common symbols everyone can agree on, and the more of your brainpower is going to be poured into into learning and following important social rules. Conversely, the less invested in a religious group you are, the less motivated you’ll be to attend to the endless minutiae of social interactions and ritual, and the less reason you’ll see to stick with old systems of established meanings. You’ll be free to creatively invent new uses for old symbols, new ways of expressing yourself. You’ll be free to be creative.

…And to be lonely.

Without the robust rules, symbols, and rituals of religious or other traditional life, relationships become more fissile, people rely on each other less, and life can be lonesome and difficult. It’s a real price that creative people can pay for cutting themselves free from the web of culture.

This was certainly true for us. My family, creative as they were, were always outsiders. Other families went to church, gathered in loud jolly groups to watch the Super Bowl, had festive barbecues. Looking down on them as boring and unimaginative, our family played music, learned how to draw, saw things differently. And without the web of relationships around us, we suffered. Our lives were not easy.

As an adult, now, I don’t want to live without the strong web of relationships that makes life worthwhile. But I also love channeling the muse: grabbing my guitar and playing music that doesn’t suck, or writing a poem that, you know, isn’t filled with clichés and banalities. I can’t abide the lyrics to most Christian rock, which often seems as if it were written by people who have memorized only the rudimentary 1,000-word vocabulary of Basic English (plus a few religious terms, such as “glory,” thrown in).

So bland art just doesn’t do it for me. But neither does the blasted, lonely life of a countercultural rebel who despises religion and tradition. I want both real meaning and real creativity. And I think our society could use both, too. The split between creative fecundity and relational wisdom mirrors the pernicious divide between progressives and traditionalists, and between science and religion, that makes it so hard for people in our culture to agree on anything. Studying religion, I’ve learned some of the mechanics of why creativity and stability are so hard to fit into the same boat. Now it’s time to learn how to build a more accommodating boat.

________

* Yes, there are all kinds of better, more specific names for the various accoutrements and items modish people wear than “clothes.” I know almost none of them.

† It is pretty fun to say that you “publicly state” something. It makes you feel suddenly important. I recommend it.