(This is the second piece of my response to Tony Jones’ “Challenge to Progressive Theo-bloggers.” The first piece is here.)

Whenever possible, I try to avoid gendered pronouns for God. Admittedly, this can sometimes make for clumsy syntax, but that clumsiness is a feature, not a bug.

Because the main point of this exercise is to force myself to be conscious of that word, “God,” and not to use it casually and thereby to risk forgetting or confusing or failing to account for the fact that this God I’m referring to is not your run-of-the-mill antecedent.

There are good feminist reasons to avoid gendered pronouns for God, and that’s also a big part of why I try to do so. But my main concern is not patriarchy, but anthropomorphism.

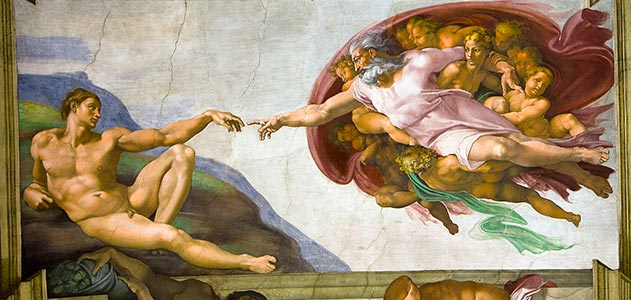

Michaelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam” is a beautiful painting, but a problematic one in that it reinforces our already extreme tendency to think of Yahweh as Zeus, or as Moses, or as Charlton Heston portraying Moses.

Michaelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam” is a beautiful painting, but a problematic one in that it reinforces our already extreme tendency to think of Yahweh as Zeus, or as Moses, or as Charlton Heston portraying Moses.

That tendency is far older than Michelangelo. I’d bet that when the book of Job was originally staged and the machine lowered God onto the scene in the third act (chapter 38 in our copy of the script), the actor playing God wore a bearded mask.

“God is not man writ large,” Karl Barth said, but we are always tempted to think of God in exactly those terms — as a man writ extremely large, bipedal, bearded, robed, sandaled and tossing a thunderbolt down from Olympus.

That leads us astray in our thinking about God and in our attempts to understand God. It leads us astray in ways that we will not be able to see until we begin to cure ourselves of the habit.

We can see this problem at work in many of the theologians who speak loudest and most often about the “sovereignty” of God. The assertion of God’s sovereignty is almost always immediately followed by an explanation of the rules governing said sovereignty — the rules that bound it, circumscribe it, hem it in and limit it. Thus “God is sovereign,” but also unable. God can do all things, except for …

And then off we go, defining the infinite and reducing God to He and Him as though discussing just another churlish Olympian. From there we end up with a God subject to wrath, or subject to a fierce allergy to all that is unholy or impure. A subject is not a sovereign.

Our tendency to anthropomorphize is both unconscious and inevitable. It distorts our thinking about God just as it distorts our thinking about all sorts of other things — about all creatures great and small, about the weather, even about inanimate objects sometimes.

Think of all those awesome YouTube clips of animals at play. The crow snowboards down the snowy roof, then flies back up to the top to do it again. We perceive, and project, human motive and emotions onto what we see. We leap to conclusions.

In a way, this is an admirable quality — a kind of empathy — but it’s also misleading. It makes for bad science. And it’s no less a danger in theology than it is in ornithology.

A crow is not a small, feathered human. And God is not man writ large.

When we yield to the temptation to anthropomorphize God — consciously or unconsciously — we inevitably reduce God, projecting onto God limits, constraints and boundaries that we, as humans, cannot help but introduce.

This, I think, is a greater epistemological concern for theology than any consideration of certainty. Pascal saw both problems as related:

This is our true state; this is what makes us incapable of certain knowledge and of absolute ignorance. We sail within a vast sphere, ever drifting in uncertainty, driven from end to end. When we think to attach ourselves to any point and to fasten to it, it wavers and leaves us; and if we follow it, it eludes our grasp, slips past us, and vanishes for ever. Nothing stays for us. This is our natural condition and yet most contrary to our inclination; we burn with desire to find solid ground and an ultimate sure foundation whereon to build a tower reaching to the Infinite. But our whole groundwork cracks, and the earth opens to abysses.

Let us, therefore, not look for certainty and stability. Our reason is always deceived by fickle shadows; nothing can fix the finite between the two Infinites, which both enclose and fly from it.

We are “incapable of certain knowledge” not just because certainty is elusive, but because we cannot grasp or comprehend the whole of what we wish to know. It overflows our capacity.

All of our God-talk and God-thinking — our creeds and constructs, our teachings and tomes, even our scriptures — are up against this limited, finite, human capacity. God is more than we can know. God is more than we are capable of knowing.

We name and label attributes of God, sometimes convincing ourselves that this is the same as comprehending them. We thus pretend that our little Flatlander brains have thereby grasped what we have actually only pointed at, boggling and reeling away to the best anthropomorphic approximation we can manage.

This isn’t to say that our partial approximations are wrong, necessarily, just that they are always partial and inadequate. Koko watched the video of the earthquake and signed, “Darn floor, big bite.” She wasn’t wrong. Given her limited vocabulary and her limited primate brain, I think she was eloquent, poetic even. But those four words only begin to point toward all that could be said or known about earthquakes.

Here is a remarkable thing that I love about that ancient play about Job, when the God in the first act finally goes off in the third. Part of what the character of God says there is typical of what the Gods always say to us mortals in ancient plays: “Who are you, a mere mortal, to judge me, a God?” But the God in Job also makes another point, affectionately explaining to Job that he is incapable of grasping the explanation he seeks — the explanation he properly demands.

God does not say this as a defense, nor as a condemnation. God is a bit testy about all the nonsense Job’s friends have been spouting, but God delights in these humans even more than God delights in ostriches and Orion.

Poor Job is, like all of us humans — including the humans who wrote Job — a finite, fallible, fragile creature. We humans have limits. Our primate brains are large and wondrously capable, but they are not infinitely capable. We cannot know everything we want to know and we cannot express everything we want to express. We cannot know everything there is to know or even grasp the scale of the difference between all that we can know and all that we cannot.

This limitation is part of our identity, our creatureliness. It’s not a flaw, just a limit. And God — or, at least, the heavily anthropomorphized God of Act 3 of Job — loves us humans as humans, as limited, fallible, fragile little creatures with our vast-but-not-boundless potential and capacity.

And but so, this is something we must always keep in mind — that God is more than can be kept in something as finite as our minds.

Our best ideas and approximations, our creeds and constructs, formulas and formulations, scriptures and systematic theologies are, at their best, still inadequate. “Darn floor, big bite.” “Trinity.” “Homoousios.” Our limited vocabulary and limited primate brains can be eloquent, but we can never comprehend comprehensively.

The danger of forgetting that is the danger of making our constructs into idols.

And so, partly as a discipline to force myself to remember that, I try to avoid pronouns for God. If that sometimes trips me up over clumsy syntax, then the pain of that stubbed toe is a helpful reminder.

We cannot know all there is to know about God. But I believe that we can know all that we need to know about God. That’s what I intend to discuss in part 3, wherein I will utterly fail Tony’s God-blogging challenge by violating the “not about Jesus” rule.