(Part 1 of this post is here.)

I attended a private, fundamentalist Christian school. I also belonged to a fundamentalist local church.

Our church was an independent, fundamentalist, Baptist church. It had once been a Northern Baptist church, then split off to join the Conservative Baptists, then split off again to join the still-more-conservative General Association of Regular Baptists before eventually splitting off from the GARB to go it alone.

But our independent, fundamentalist and Baptist church should not be confused with an Independent Fundamentalist Baptist church, which is a very specific, and quite different, brand of fundamentalism.

There are many such different brands of fundamentalism. You’ve got your Calvinist fundies and your Arminian fundies, your premillennial dispensationalist fundies and your postmillennial dominionist fundies, your raucous holy rollers and your somber frozen chosen.

What all these groups have in common is that they all believe they have unambiguous access to absolute truth through the literal reading of the inerrant, infallible Bible.

I’ve strung together a bunch of adjectives there, but each is important for understanding the all-or-nothing, package-deal aspect of fundamentalist Christianity. The belief that the Bible is the “inerrant” and “infallible” word of God means that every word of it is true, without error, and thus it stands as the ultimate arbiter of absolute truth. The belief that this absolute truth should be read literally entails that it is accessible to us, which means it cannot leave room for ambiguity and honest disagreement between two well-intentioned, Spirit-guided readers.

So while the absolute truth of the Bible must obviously be defended against worldly enemies such as liberals, modernists and secular humanists, it’s even more important that this absolute truth be defended against other fundamentalists who disagree on any point of doctrine, however seemingly minor. We worldly types are a favorite bogeyman for fundies, but “the world” — a category just as comprehensive as it sounds — cannot pose an existential threat to the core of fundamentalist identity. Other fundamentalists can.

“The world” is wrong, but our errors reinforce fundie identity and fundie epistemology. We are wrong because we reject the absolute truth of the literal reading of the inerrant, etc., Bible. Those other fundamentalists, however, claim to accept the same epistemology, and that threatens to undermine the whole conceit, because if it is indeed true that the Bible provides us unambiguous access to God’s absolute truth, then all fundamentalists ought to believe exactly the same things.*

This is why if you go to a pre-Tribulation premillennial dispensationalist Bible prophecy seminar, you won’t hear speakers wasting their breath condemning historical or liberationist readings of the book of Revelation. They focus instead on the graver, existential danger posed by alternative fundamentalist readings, attacking the post-tribbers and mid-tribbers who distort God’s absolute truth even though they ought to know better.

That’s related, I think, to what Freud called the “narcissism of small differences,” but it makes a lot of sense from the fundies’ point of view. The belief that an inerrant Bible provides us access to absolute truth cannot be reconciled with the existence of competing fundamentalists who disagree on even the most esoteric points. Those groups can be attacked or avoided, but not accepted and accommodated. There’s no room for “let’s all agree to disagree.”

That helps to explain why there is such a multiplicity of fundamentalist denominations. And also why they tend to be so small.

And that smallness poses a big challenge for anyone trying to run a fundamentalist school. A functional school needs an adequate number of students and staff. Huge fundie mega-churches, like the sordid Hyles-Anderson creep-show in Indiana, are big enough to run their own schools, staffed and attended only by uniform members of their own churches. But most fundamentalist churches are nowhere near big enough to do that. For most fundie churches, having a fundie school for your kids means having to collaborate and co-operate with other churches — including with other churches that may not agree with yours on every detail of doctrine.

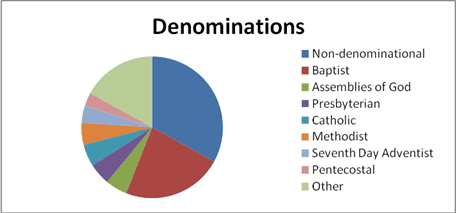

The website for my alma mater, Timothy Christian School, says that its students come from 150 different churches in 70 different towns. And as that pie-graph up above shows, those churches represent quite a diversity of religious traditions and perspectives.

When I was a student at TCS, I had many classmates and teachers who were members of Pentecostal and Assemblies of God churches. Those churches were just as fundamentalist as my own, and our churches were fully in agreement on many points of fundie doctrine — young-earth creationism, Rapture prophecy, inerrantism, literalism, KJV-onlyism, etc. (This was the late 1970s and early ’80s, so anti-abortionism hadn’t yet arisen to eclipse all of those as the pre-eminent identifier.)

But those Pentecostal and AofG churches also taught the charismatic gifts of the Holy Spirit, including a big emphasis on speaking in tongues, which they taught was the sign of the baptism in the Spirit and a necessary mark for any true Christian.

At my independent, fundamentalist Baptist church, speaking in tongues was forbidden. It was seen as, at best, a heresy, and at worst as evidence of demonic possession. Anything even slightly charismatic-seeming was frowned on at my church. I remember once someone raised their hands above their head during worship. Once.

One life-long member of our church graduated from Bible College and then went off to the Urbana missions conference where he went forward and committed his life to full-time Christian service as a missionary. Our church was very big on missionaries, providing financial support for dozens of them through our local mission committee. From a very young age, we were taught that full-time Christian service as a missionary was the highest calling for any Christian.

But it turns out that this guy from our church had signed up with a fundamentalist mission agency that our mission committee had come to regard with suspicion. The head of the agency, apparently, had been asked in an interview about speaking in tongues. He condemned the practice and said he had never done it himself, but he also said that he supposed, maybe, it might not be too grievous a sin if someone were to do it privately as part of their own personal prayer and devotions. This was regarded as an unacceptably lenient stance toward speaking in tongues, and so our mission committee denied the request for support from our own home-grown missionary to-be.

The point here is that the form of fundamentalism taught by our church was utterly incompatible with the form of fundamentalism taught by some of my classmates’ and teachers’ churches. Our church taught that they were not legitimate Christians, and their church taught that we were not legitimate Christians. Both sides took this disagreement very seriously, with the denial/acceptance of speaking in tongues regarded as a theological disaster equivalent to embracing evolutionary science or textual criticism. Each side regarded the other as violating the all-or-nothing package-deal of fundamentalist Christianity.

And yet there we all were at Timothy Christian School. We were studying together, praying together and taking turns sharing our personal testimonies in chapel together. We were agreeing to disagree, respecting one another despite our differences. We’d have shuddered to hear the word, but our practice was downright ecumenical.

We couldn’t both be right. We might both be wrong. We might both be partly right and partly wrong. And those weren’t supposed to be possibilities for people with direct access to the infallible word of God.

Our very presence there together forced us to acknowledge our difference of opinion. And that, in turn, forced us to acknowledge that such diversity of opinion seemed inevitable even among those of us committed to a literal reading of the inerrant, infallible Bible.

In other words it forced us to accept, at least implicitly, that unambiguous direct access to absolute truth might not be quite as accessible as we liked to pretend. And just like that, there goes the whole fundie epistemological construct and all the all-or-nothing, package-deal claims that go with it.

I could not have articulated any of that at the time, when I was still a student there at Timothy. But looking back, much later, I came to see this as a saving grace. It spared me from the intense crisis of faith I might otherwise have experienced when many of the ingredients of the package-deal I had been taught were destroyed in their collision with reality. The truths I had learned had been chained together with a ludicrous bundle of lies — young-earth creationism, PMD “prophecy,” etc. — but the chains did not hold because I had already come to see that the chains were not real.

Our teachers at Timothy Christian told us that our faith was an all-or-nothing package deal, but the diversity of traditions and theologies there at the school — as narrow as such diversity may have been — showed us otherwise. That provided us an advantage over the home-schoolers and other fundie kids who were schooled in more denominationally homogenous settings. Those kids were being set up for a crisis of faith.

We were too, but we were also — accidentally and inadvertently — being prepared to deal with it.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* This isn’t to say that fundamentalists think that reading the Bible requires no interpretation at all. They acknowledge, at least nominally, that some parts of their doctrine are based on less-than surface-level readings of passages they admit can be confusing. So even a literal, common-sense approach to reading the Bible, they concede, may require what they like to call “rightly dividing the word of truth.”

But just as fundamentalists insist that the Holy Spirit guided every word of the Bible’s composition to guarantee its inerrancy, and — as many, if not all, fundies believe — that the Holy Spirit watched over every word of the Bible’s translation, to ensure the inerrancy of our English King James Version, so too they believe that the Holy Spirit will guide the faithful reader to ensure that reader is rightly dividing the word of truth. Inerrancy is not simply a claim about the nature of the Bible, but also a claim about our access to it — our ability to read the inerrant Bible inerrantly.

This framework ups the ante on any disagreement over the meaning of the Bible. If Bob and Jack disagree, then one of them must not be obeying the guidance of the Holy Spirit. And since Bob knows in his heart that he is a well-intentioned, real, true Christian who is genuinely seeking the Spirit’s guidance, that must mean that Jack is not. And Jack is assuming the same thing about Bob. It tends to get ugly from there.