Since this morning’s “Biblical Family of the Day” post involved the story of the rape of Dinah from Genesis 34, here’s a bit more on that passage from a recent discussion by Lauren Tuchman at State of Formation, “The Presence and Absence of Women: Reflections Upon the Rape of Dinah“:

Every year as I read this parsha, I am struck by Dinah’s total silence. The narrative surrounding her rape by Shechem is told strictly through the perspective of her father and brothers, Shimon and Levi who, upon receiving word of Dinah’s rape, exact violent revenge against all of the male inhabitants of the city.

… Dinah’s complete absence and lack of human agency in this narrative I find deeply troubling. Far too frequently, women and their experiences are rendered completely invisible in our sacred texts. We hear of Shimon and Levi’s violent anguish, but what of Dinah’s?

… What I find all the more troubling is the fact that if Dinah was indeed raped, as the pshat–or simple meaning of the text clearly conveys, her experience is invisible, and the only thing that seems to matter here is her familial honor. Feminist Biblical commentary has done much to give the voiceless women in our sacred texts a hearing. Although we can never know how Dinah felt, we can, through feminist hermeneutics and Midrash, seek to uncover and recover that lost strand in our tradition, making Torah all the richer.

What Tuchman says here about Dinah, and the title of her post — “The Presence and Absence of Women” — seems to apply to many of the horrifying biblical passages we’ve looked at here in that “Biblical Family” series.

Think of those 10 women shut away after being used in the conflict between Absalom and David. Or of all those other unnamed concubines and female slaves. Or even Vashti. She was a queen when we first meet her in that story, but what became of her after that? Over and over, as Tuchman says of Dinah, their “experience is invisible.”

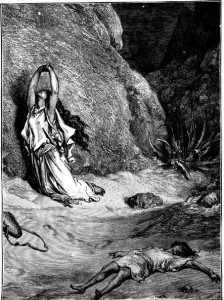

One partial and strange exception to that is the story of Hagar, the slave of Abraham’s wife, Sarah.

The Registered Runaway has a thoughtful discussion of the story of Hagar in the book of Genesis. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say the stories of Hagar, since those passages in Genesis seem cobbled together from different storytellers with very different views of what Hagar’s story means.

RR writes:

Hagar was an Egyptian. A slave to Sarah while [she and] Abraham stayed in Pharoah’s palace. When the two got the boot out of Egypt, Hagar was packed up like luggage and carted along with them. Away from everyone and everything she ever knew.

She was a minority in every sense of the word. Her gender, race, nationality and social status put her in the bottom of the barrel. Nothing more than a means to an end. Something to be traded, used and discarded. Born to be little so her master could be great, her existence nothing more than a sad roll of the dice.

Hagar is another of the many women in the Bible who is misused, mistreated and disregarded by the righteous heroes of the story. But unlike with Dinah or those many nameless just-a-concubine women in those other stories, Hagar’s experience is not wholly invisible. We get to see her experience and her perspective, even when it makes Abraham and Sarah look bad.

Hagar’s story includes a familiar motif — flight into the wilderness, abandonment and despair, followed by divine visitation and the promise of a blessed future. That same motif is seen in the stories of Abraham, Jacob, David and Elijah, but here it centers on a Gentile slave woman.

“You are the God who sees me,” Hagar says. The God who sees me.

Did Dinah ever say that? Or those royal concubines locked up after being used by the king and the prince?

Could they say that? The stories we have of them don’t suggest it’s true. Their experience is invisible in these stories, and if we judge only by these stories without the kind of “feminist hermeneutics and Midrash” Tuchman calls for, then it seems as if their experience was invisible even to God.

RR continues:

What stands out is how this story is told. Or rather not told. … Church history has traditionally trashed Hagar as an example of the sinful. Of the fallen. And within the same breath, they say Sarah is an example of the heavenly. Augustine compares Hagar to the city of the Earth and Sarah the city of Heaven. Aquinas separates the children of Sarah and Hagar into the “redeemed” and the “unredeemed.”

But God saw Hagar, even if we refuse to look.