Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist; pp. 167-174

During a long, rambling conversation over dessert with Rayford Steele, Hattie Durham reminds her former non-boyfriend that he was always too old for her anyway. “[Buck] and I are closer in age,” she says.

She underscores the point on the following page, saying of Nicolae Carpathia: “He was only about as much older than Buck as Buck was older than I.” At that point I felt like I was reading a word problem from the PSATs (“Rayford is twice as old as Hattie. Nicolae is as much older than Buck as Buck is older than Hattie. If Hattie is 22 years old, what color is the Norwegian’s house?”).

This discussion of the characters’ relative ages got me to thinking about my own age relative to theirs — and that’s a disastrous line of thinking when it comes to the central claim of these books. Buck Williams was 29 years old in the first book of this series, which was published in 1995. In 1995, I was 27 years old, so Buck is two years older than me.

That would mean that today, in 2013, Buck is 47 years old. But Buck Williams doesn’t get to live to see 47 because seven years after these books begin, Turbo Jesus comes back and destroys life, the universe and everything. So the world was supposed to end in 2002.

Spoiler alert: The world did not end in 2002.

Heck, in 2002, Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins hadn’t even finished writing this series of books.

But wait, that’s not entirely fair. That first book wasn’t set in 1995. It was set in an undefined not-so-distant future. The problem is that the not-so-distance between 1995 and this future is asked to serve two contradictory functions.

On the one hand, this distance must be very, very short because the story begins with the Rapture. LaHaye, like everyone who believes in the idea of the Rapture, believes that it is imminent. Type “Imminent Rapture” into Google and you’ll find hundreds of thousands of results, even though the phrase is redundant. To believe in the Rapture is to believe that it could occur at any second — maybe this very day, maybe this very hour, maybe before you finish reading this post or even this sentence! (Phew — looks like we’re all still here.)

A Rapture-believer like Tim LaHaye cannot provide one of those sci-fi introductions when telling a Rapture story. It cannot be specific, like the first lines of John Carpenter’s 1981 film Escape from New York: “In 1988, the crime rate in the United States rises four hundred percent. …” No one knows the day or the hour of when the Rapture will come. But it is undoubtedly imminent. No one knows the day or the hour, but it must always be possible that it is this day and this hour.

The imminence of the Rapture means that this book, published in 1995, also had to, at least in a sense, be set in the world of 1995. The story couldn’t include any elements that would have seemed “futuristic” in 1995 — flying cars, rocket packs, domed cities, cell phones, wi-fi, a black president, etc. All of those would have signaled that the Rapture is not imminent, but some future event still years or even generations away. They would serve to increase the not-so-distance of the book’s future setting, contradicting the imminent-Rapture requirement that this not-so-distance be as short as possible.

The imminent Rapture requires that this story be set in a present that’s just about to happen. That presented Jerry Jenkins with a bit of a dilemma as it took the authors 12 years to finish publishing their narrative of how they believe the final seven years of history will unfold. Jenkins needed to preserve the Rapture’s imminence by avoiding futuristic technological details and only including the technology of the present day, but the present-day technology of 2007 was quite different from the present-day technology of 1995. Jenkins’ cleverly pragmatic response to this problem was simply to incorporate new technologies as they arose while pretending this doesn’t create any anachronistic conflicts between his earlier books and his later ones. So in the first book we have airport pay-phones (ask your parents) and by the third book we have cell phones. That can sometimes be jarring, but I give Jenkins a pass on this because telling a story set in the imminent future is a difficult business.

The one bit of futuristic technology the authors do include in their story is Dr. Chaim Rosenzweig’s Miracle Formula. The chemistry and biology of this seems so unlike anything possible today that the presence of such a formula in our story seems to push its setting decades further into the future, destroying the whole sense that the Rapture it describes might be “imminent.”

I suppose the authors might counter that Rosenzweig’s formula wasn’t so much a scientific breakthrough as it was an actual miracle. Like the Rapture itself, it was an act of divine intervention in the natural world and thus, like the Rapture itself, something that might be regarded as imminent. That’s a bit unsatisfying, though. To paraphrase Arthur C. Clarke, any act of miraculous intervention is indistinguishable from sufficiently advanced technology.

The larger problem for the authors and for their insistence on the imminence of this story is that their focus on avoiding futuristic technology didn’t extend to an avoidance of futuristic politics. The political world in which Left Behind (1995) is set has as much relation to present-day politics as the technological world of Star Trek has to present-day technology. Peace in the Middle East, for example, is presented as a fait accompli. Israel is said to be at peace with all of its immediate neighbors — a state of affairs the authors describe as somehow involving Israel absorbing all of its immediate neighbors, annexing much of Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Egypt without disrupting or disturbing the residents of those countries while also not altering in any way the distinctive identity of Israel as a Jewish nation.

Such a development doesn’t seem particularly imminent. It seems utterly unlikely, if not impossible. For the authors, though, this is something that will and must happen — a fulfillment of what they believe is divine prophecy. They also believe this to be a necessary precondition for the “imminent” Rapture. Let’s play along with that idea as best we can. Forget about 1995, start with today, July 26, 2013. How long do you imagine it would take to get us from where we are today to this prophesied future world of a Greater Israel beloved and unthreatened by those neighbors it hasn’t yet absorbed? Can you imagine this happening in a single decade? A single generation? A single century?

I can’t. And if this development is a prerequisite for the Rapture — if this must be accomplished before the Rapture can occur — then it seems to me that this Rapture cannot be in any way described as imminent. If this is a necessary precursor to the Rapture, then — based on Tim LaHaye’s own rules of “Bible prophecy” — the odds are that we’ll see a colony on Mars long before this “imminent” Rapture could ever occur.

And keep in mind that these books are about prophecy, not playful prediction. If the future they foretell does not come to pass as they foretell it, then these books utterly fail. That is their central claim.

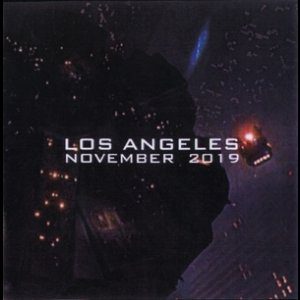

That makes for a very different sort of problem than the fun-but-mistaken discussion of the supposedly failed predictions of science fiction stories. George Orwell wrote 1984 in 1949. I quoted from Escape From New York above, which described a future world of 1988 in which Manhattan had been transformed into a penal colony. The image above is from the 1982 movie Blade Runner, which portrayed the Los Angeles of 2019 (getting close!) as a cramped city wracked by climate disruption and police drones (getting close!). But Blade Runner also predicted “off-world colonies” and androids indistinguishable from their human creators — developments that seem more than six years distant from our present. Or consider one of my favorite books, Infinite Jest, which depicted the Year of the Depends Adult Undergarment as a 2009 that wasn’t even called “2009.” David Foster Wallace nearly predicted Netflix, but northern New England hasn’t been transformed into a concavity overrun with mutant feral hamsters, so he loses points for “accuracy” there.

But this game of spot-the-failed predictions misrepresents what those stories are about. They’re not about the future, but about the present. The point wasn’t an attempt to make an accurate prediction about where we are inevitably headed, but a way of using such predictions as a mirror to reflect and examine where we are now. The words on the screen in that still from Blade Runner really mean just the same thing as the words at the beginning of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil: “Somewhere in the 20th Century.” Those stories aren’t predictions about the future, but rather commentaries on the present (and on the perennial).

That’s also true for the alleged source material for the Left Behind series — the apocalyptic literature of the Bible. Apocalyptic literature is not making predictions about the future, but rather it attempts to unveil (“Revelation”) the true reality of the present or perennial human condition. It is prophetic in the sense that, like the prophets, it passes judgment on the world and renders a verdict. But it is not meant to be “prophetic” in the carnival-huckster sense of foretelling future events.

Unfortunately for LaHaye and Jenkins, their books are meant to be predictive “prophecies” in that latter sense. These books are fictional, but they’re meant to provide a fictionalized description of future events that will occur just as described — a kind of historical fiction about the future. That means the standard for accuracy that it would be unfair to apply to 1984 or to Blade Runner must be applied to these books. By fudging on the precise year in which their story is set they don’t allow us to state conclusively that their predictions have failed and that their prophecies have gone unfulfilled. But we can state conclusively that the imminent “Rapture” they continue to prophesy was not and is not and cannot be “imminent.”

This may seem like an overlong response to just a couple of sentences from Hattie in this section of Nicolae, but her whole conversation with Rayford is infused with her nostalgic musing about her past. That past, even as sketchily and carelessly described by Jenkins, is situated in time. Combined, then, with Hattie’s discussion of all the characters’ ages one gets a clearer sense of when the imminent present of this scene is set — and that actually seems to be earlier than 1995.

“Think about it, Rayford. All I ever wanted to be was a flight attendant. The entire cheerleading squad at Maine East High School wanted to be flight attendants. We all applied, but I was the only one who made it. I was so proud. …”

Hattie is supposed to be a member of Generation X, but Jenkins describes her childhood dreams and teenage fantasies using his own Baby Boomer imagination. This seems like something out of the world of Bye Bye Birdie or Mad Men. If Hattie grew up reading Vicki Barr Flight Stewardess books as a child and she’s in her early 20s, then this story can’t be set much later than the Reagan years — 1985 rather than 1995.

Back in 1985, of course, Tim LaHaye was preaching about the same “Bible prophecies” he later fictionalized in 1995 and that he’s still preaching today in 2013. He was preaching that the central focus of every Christians’ life ought to be the Rapture. And the Rapture, he said in 1985, is imminent.