“It’s 2013, for God’s sake,” the sports talk radio host said, repeatedly, this afternoon. “We’re supposed to be beyond all this.” That same phrase was echoed by several callers.

I was listening to sports talk while running errands today because 4 p.m. was the Major League Baseball trading deadline and, as a Mets fan, I was worried that they’d be trading Matt Harvey for Jim Fregosi. (They didn’t, phew.)

But the trade deadline was kind of a dud, so the big news on Philly sports talk today was instead about the recent video of a white Eagles wide receiver boasting that he would “jump that fence and fight every n—- here, bro.”

That’s depressing in a way that makes one want to say, along with all those callers on the radio, “It’s 2013, for God’s sake.”

That’s depressing in a way that makes one want to say, along with all those callers on the radio, “It’s 2013, for God’s sake.”

But while it may be 2013, we’re still a long way from being “beyond all this.” We’ve made some progress, no doubt, and one sign of that progress was the unanimity of the hosts and callers in condemning the receiver’s stupidity and bigotry. That’s encouraging, considering that sports talk radio is not always the best place to turn for progressive commentary. (I also didn’t listen for very long, so I don’t know if all the callers were unanimous — and I don’t even want to think about the callers they screened out or about the sorts of things that will be written in the comments of the story linked above at Philly.com.)

We’ve made progress, but the past is still with us. As Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.”

That same truth applies to Emily Badger’s fascinating Atlantic piece, “Hunger Makes People Work Harder, and Other Stupid Things We Used to Believe About Poverty” (via Alan Bean).

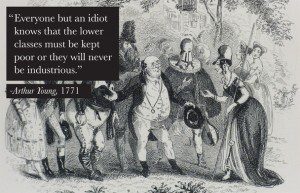

Badger offers a survey of 18th-century views regarding the poor and working classes. The remark by Arthur Young in the image (from Badger’s piece) above reflected the conventional wisdom of the upper classes in 1771: “Everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor or they will never be industrious.”

But Badger walks us through a paper by Georgetown University economist Martin Ravallion in which he explores the ways in which we’ve learned to correct those wrong ideas:

Most fundamentally, as Ravallion writes, we’ve gone from thinking that poverty is a necessary ingredient for economic development to thinking that poverty constrains it. Numerous related assumptions have (mostly) fallen along the way: The poor were at fault for their own poverty (through moral weakness, alcoholism, laziness, a penchant for making too many babies). The poor were born that way, and nothing could be done about it. Besides, poverty had its own utility: If people weren’t hungry, they wouldn’t work. Thus, poverty was a social good.

Today, we mostly agree on three ideas that Ravallion illustrates form a startlingly recent consensus: Poverty is bad, it’s possible to do something about it, and government policy can play a role. That last part doesn’t just mean propping up the floor beneath poor people so they don’t become totally destitute. It means helping people out of poverty all together.

Those three ideas are certainly true. No credible data or argument suggests otherwise. But who is this “we” who mostly agrees to this consensus? It may be a consensus among those who care about truth, data and credible arguments, but I’m not as confident as Ravallion that this is a majority view. The “numerous related assumptions” he says have “fallen along the way” reads like a transcript form a 2012 Republican presidential primary debate.

Badger concludes:

This whole story suggests that we’ve come a very long way in two centuries from a time when we didn’t even conceive of poverty as a problem. But it’s also possible to see in this summer’s Congressional debates over food stamps echoes some of these same outdated ideas – that aiding the poor will only discourage them from working, or that doing so is simply not the government’s job. “The difference today,” Ravillion writes, “is that most people in the world clearly do not agree.”

I think saying “it’s also possible to see … echoes of these same outdated ideas” is a horrible understatement. It’s impossible not to see them, as they dominate much of our politics, as well as the austerity politics crippling much of Europe.

We have, indeed, “come a very long way,” but again, the past is not dead. Arthur Young is alive and well and he’s demanding deep cuts to food stamps.

It’s 2013, for God’s sake. But we’re still a long way from being beyond all of this.