Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist; pp. 195-201

We’re about to set off on a rollicking little adventure as Buck Williams becomes a man on the run.

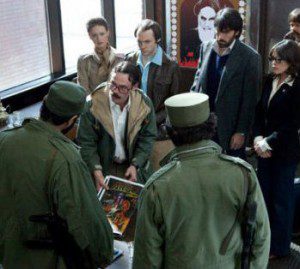

This is that story where the hero has to sneak across the border without getting caught. I love that story. Most people love that story. Ben Affleck’s movie Argo told that story and won a bunch of Oscars for it last year.

This story always works because it’s so simple. The hero is at Point A and has to get to Point B while the villains — all the king’s horses and all the king’s men — are trying to stop him.

Why does the hero have to get to Point B? That doesn’t really matter. “The audience don’t care,” Alfred Hitchcock said. All we need to enjoy this story is what he called the “MacGuffin“:

The main thing I’ve learned over the years is that the MacGuffin is nothing. I’m convinced of this, but I find it very difficult to prove it to others. My best MacGuffin, and by that I mean the emptiest, the most nonexistent, and the most absurd, is the one we used in North by Northwest. The picture is about espionage, and the only question that’s raised in the story is to find out what the spies are after. Well, during the scene at the Chicago airport, the Central Intelligence man explains the whole situation to Cary Grant, and Grant, referring to the James Mason character, asks, “What does he do?” The counterintelligence man replies, “Let’s just say that he’s an importer and exporter.” “But what does he sell?” “Oh, just government secrets!” is the answer. Here, you see, the MacGuffin has been boiled down to its purest expression: nothing at all!

My guess is that the adventure sequence that begins here and continues for the next several chapters is a favorite section for fans of these books. I think that’s because those readers have learned — from hundreds of Hollywood movies — to enjoy the ride just as Hitchcock says. Don’t sweat the MacGuffin, that will only distract you from the fun of the chase and from seeing how our hero is able to overcome all the obstacles the story throws in his path.

These chapters of Nicolae aren’t written any better than the rest of the book, but the simplicity of the formula here gives Jerry Jenkins a clarity of purpose and a narrative momentum that the rest of the book is lacking. If we just accept the validity of the MacGuffin, we can go along for the ride. And even though Jenkins’ prose throws as many obstacles in the reader’s path as his story sets before Buck Williams, that simplicity and clarity will get us to ask the vital question “What happens next?”

Reviews of the Left Behind books within the evangelical subculture frequently refer to these books as “page-turners” — a description that, most of the time, is utterly wrong. But here it’s somewhat appropriate. If we read this section the way we’ve been trained to by Hitchcock and a thousand other skilled storytellers, we’re propelled through this adventure. Once we accept the premise implied by the MacGuffin — that it is very important that Buck Williams gets to Point B — we become just as determined as he is to get him there, and all the false starts, wrong turns, tangents, distractions, banalities and dull patches that Jenkins lays across our path aren’t going to stop us from seeing this thing through all the way to Point B.

Unfortunately, though, this is not North by Northwest. I don’t just mean that Buck Williams is no Cary Grant or that Jerry Jenkins is no Alfred Hitchcock — although both of those are certainly true. I mean that this story isn’t presented in a way that allows us to enjoy it the way we can enjoy North by Northwest. We’re not just being told a thrilling story for the sake of entertainment — we’re being taught a theological lesson. Jenkins’ “co-author” here is Tim LaHaye, a “Bible prophecy scholar” who chose to produce these novels in order to teach us what he believes the Bible teaches about the End Times — about real events that will really happen very soon here in the real world.

This story won’t allow us to accept a MacGuffin boiled down to its purest form of nothing at all. In Left Behind, the MacGuffin always matters. We can’t ever just relax and go along for the ride: Point A to Point B because MacGuffin. We’re supposed to be learning about Point A, and about Point B, and about whatever the reason it is that our hero has to get from one to the other.

So let’s just briefly take a look at some of those elements before we set off with Buck Williams on the race to Point B.

The MacGuffin here is a person: the former Rabbi turned fundamentalist Christian evangelist Tsion Ben-Judah. Point A is Israel. Point B is Not Israel. The plot, in other words, is that Buck has to help his friend Tsion escape from Israel.

That’s odd, considering what we already know about the world of this story. In this world, Israel is the only remaining sovereign nation on Earth — the only place in the entire world not controlled and policed by the Antichrist’s one-world government. And the authors have assured us that the geographically expanded Israel of these books is a prosperous, peaceful nation on the best of terms with all neighboring people — a country without all the security barriers and checkpoints and walls that now line the Palestinian territories.

That means our story now involves our hero fleeing from the one peaceful country on Earth into the hands of the apotheosis of evil. Buck and Tsion are trying to escape to the Antichrist. Buck and Tsion are desperately racing to get into a tyrannical dictatorship led by the Beast himself, a madman who just a few days ago started arbitrarily killing millions of people by nuking New York, Washington, London, Cairo, Chicago, San Francisco, etc.

So already the basic formula of Point A to Point B is weirdly broken. It’s like we’re reading about Andy Dufresne trying to break into Shawshank prison.

That wouldn’t be an insurmountable problem if we were given some easily ingested explanation for why Tsion has to flee Israel. The usual MacGuffin-ish way of accounting for such a need to flee a free country involves the hero being falsely accused of some crime. Jenkins nods in that direction, briefly, with a muddled bit about the death squads who killed Tsion’s family claiming to have been hired by him, but no one — including the author and the readers — seems to find this convincing. The death squads are after Tsion now not because of some half-hearted frame job, but because he converted to fundamentalist Christianity.

Tsion is forced to flee Israel, in other words, because he is a Christian. Jenkins tells us this repeatedly in these pages and in the chapters that follow, always in a way that suggests its obvious and well-known that any rabbi who converted to Christianity would be hunted down and killed by the Israeli government. Jenkins just assumes that readers know this to be the case: You know how those Jews are, they kill Christians.

As much as I’d like to stick with the standard practice of not sweating the details of the MacGuffin, that’s difficult to do in this case because the MacGuffin is blithely, but viciously, anti-Semitic. Take away the anti-Semitic assumptions and nothing in these chapters makes any sense. It’s not an incidental, background slander here — anti-Semitism is the engine that drives the narrative.

And we’re not talking about some slightly offensive ethnic stereotyping, either. This is hard-core, blood-libel stuff: Israeli death squads killed Tsion’s family, which is to say Jews kill Christian babies. This MacGuffin isn’t just a set of “secret plans” we can accept and ignore thereafter. This MacGuffin is an old and deadly lie at the root of centuries of slaughter.

Why would anyone want to flee into a tyrannical dictatorship led by Satan’s own hand-picked evil mastermind? To get away from the Christ-hating, Christian-children-murdering Jews.

Throughout the pot-boilerplate, paint-by-numbers adventure in the chapters to come, we can’t avoid that. Even when Jenkins semi-capably creates a bit of familiar tension with familiar plot devices — the traffic stops and check-points from a thousand superior escape thrillers — we’re aware that the tension and suspense we’re meant to feel is based on a presumption about some intrinsic malice and danger attributed to all Jews. The authors assume we share that presumption.

That gives this whole adventure sequence over the following chapters a Birth-of-a-Nation feel to it. Unlike Jerry Jenkins, D.W. Griffith was a masterful artist, but while The Birth of a Nation is a work of art, it’s also a repugnant film. Griffith directed his whole genius to getting his viewers caught up in a thrilling adventure story, but the only way to get caught up in that story is to accept the racism and racist mythology that drives his plot. Griffiths’ racist enthusiasm isn’t something overlaid on top of his story, it is the premise of that story. Without it, the story cannot happen.

Am I suggesting that Tim LaHaye, Jerry Jenkins, and the millions of Very Nice Christians who enjoyed Nicolae as a “page-turner” are all, therefore, vicious anti-Semites?

Well … let’s not jump to conclusions. Let’s work our way through the adventure of Buck and Tsion and their thrilling escape from Israel back into the safety of the Antichrist’s one-world government. Let’s consider the story as it unfolds and all that Buck and Tsion and other characters have to say in the chapters to come. And then, after our heroes arrive at Point B, we can consider that question again.