Mallory Ortberg offers a terrific guide to “Pre-code Movies Worth Watching,” wherein she solidifies her status as one of my favorite people on the Internets with her take on I Am a Fugitive From a Chain-Gang:

My absolute favorite film of all time, bar none. You have to see it. YOU HAVE TO SEE IT. Oh, God, I want to give away the ending so bad, but I won’t, even though it’s been over 80 years. It’s one of the most absolutely harrowing endings in film history, and completely unthinkable for a studio film to end on that kind of a note at the time. There’s a hiss and a whisper and footsteps in the dark and an admission of something that’s impossible to believe. Oh, God, watch it yesterday and call me when you’re done so we can talk about it for hours.

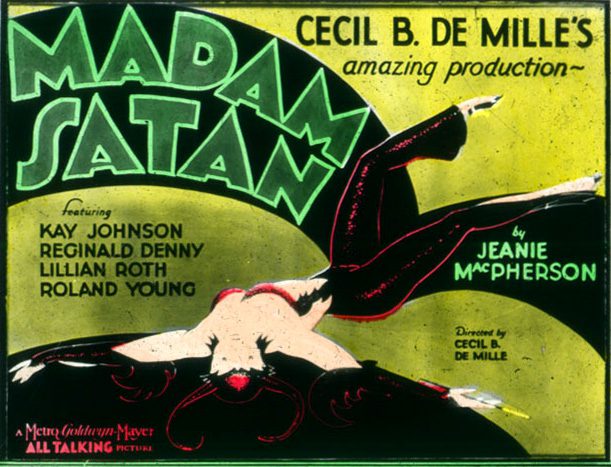

The code of “pre-code” was the Motion Picture Production Code, a long, “touch not, taste not, handle not” list of guidelines and taboos from the Hollywood studio censors outlining what topics and depictions were off-limits.

Ortberg’s survey offers some helpful (and funny) categories, starting with “Worth Watching For Any Reasons” and then descending into others such as “Less Well-Known Remakes,” “If You Want to Get Into Pre-Civil-Rights-Era Racial Dynamics,” “Ugh, If You Must, They’re ‘Important’ But I Hate Them,” “If You Want to Take a Deeply Uncomfortable Journey to Another Time,” and “Worth It for the Titles Alone.”

Oh, those titles. Here’s Wikipedia’s long list of pre-code movies — a list that could easily provide all the band names we’ll ever need for the next decade. A small selection, just from those released in 1933:

- A Shriek in the Night

- Air Hostess

- Ann Carver’s Profession

- Beauty for Sale

- Broadway Through a Keyhole

- Ecstasy

- Ex-Lady

- Girl Without a Room

- The Mayor of Hell

- Midnight Mary

- The Past of Mary Holmes

- Roman Scandals

- She Done Him Wrong

- She Had to Say Yes

- Should Ladies Behave

- The Sin of Nora Moran

- The Secret of Madame Blanche

- The Song of Songs

- When Ladies Meet

- The White Sister

- Wild Boys of the Road

- The Woman Accused

Those titles seem to have functioned the way the movie rating system functions today. They may not have had such a thing as an “R-rating” in 1934, but I think audiences knew what they could expect from movies with titles like Fugitive Lovers, Massacre, or The Road to Ruin.

A survey of pre-code movies is an excellent antidote to much of the nonsense we sometimes hear about “old-fashioned morality.” Our grandparents’ generation is sometimes said to have lived in a more innocent time, before America went to Hell in a handbasket and began abandoning traditional morality. But it turns out our grandparents were lining up at the box office to see movies like She Couldn’t Say No or The Unholy Three.

Those pre-code movies are a good reminder that much of what gets glibly described as “traditional morality” was actually really, really immoral. I don’t just mean that people back then were titillated by stories they regarded as immoral. That’s always been true and probably always will be true. That’s the transgressive allure of the lurid, and there’s a sense in which it does as much to reinforce the prevailing morality as any moral code.

But the larger problem isn’t that people back then often transgressed against their “traditional morality.” The larger problem was that traditional morality itself was, in many ways, deeply perverse — it celebrated evil and injustice as exemplary rectitude while condemning and forbidding much that was good and beautiful and true.

Here’s Mallory Ortberg, again, describing an example of this, from the 1930 extravaganza Golden Dawn:

Fortify your spirit before giving this one a chance. It’s about a white woman kidnapped and raised by “African natives” (the setting never gets more specific than “colonial Africa”) who falls in love with an Englishman but can’t marry him until she’s able to decisively prove that she’s not biracial. Most of the “natives” are played by English actors in blackface, and the happy ending comes about when the lead character is released from a sacrificial ceremony for being “pure white,” so gird your loins if you decide to watch it. OH. And it’s a musical. So.

But then the film industry came up with the Hays Office and the Motion Picture Production Code to enforce moral standards.

Take a look at that code, particularly at it’s lists of “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls,” and you’ll see that it simply codified that same traditional immorality. Here, to get specific, are items No. 6 and No. 11 from the “Don’ts” — things that “shall not appear in pictures produced by the members of this Association, irrespective of the manner in which they are treated”:

6. Miscegenation (sex relationships between the white and black races)

11. Willful offense to any nation, race or creed

No. 6 tells you all you need to know about No. 11 — what was meant by it and how it was applied. That 11th Don’t conveys an admirable sentiment of respect for every “nation, race or creed,” but it was constricted by the unstated, unexamined, almost unconscious assumptions that put that prohibition against any depiction of “miscegenation” five slots higher on the list. Thus the bad parts of “traditional morality” prevented even the good parts from being any good.

But before we congratulate ourselves for our relative enlightenment, we should remember that the dangerous tricky thing about unstated, unexamined, and (almost) unconscious assumptions is that they are all of those things. We don’t fully know we’re making them when we’re making them.

And we’re making just as many of them as Hays or Breen or Comstock or any other notoriously myopic moral censor of the past.

We have overcome and corrected some of the immoral blindnesses of “traditional morality” — 84 percent of white Americans no longer think there should be a law against interracial marriage, and that has been the majority view since way back in 1996 (!). But there are plenty of other blindnesses and unstated assumptions from traditional morality that we continue to suffer from — as well as some new ones we’ve come up with to add to the list, probably. For me, personally, for example, there’s the obvious moral blind-spot regarding …

I can’t finish that sentence yet, but I’ve no doubt that a generation from now others will have no trouble doing so. It may turn out to be a very long sentence.

The Motion Picture Production Code has not aged well because no moral code ages well. Every attempt to codify morality that goes beyond “love is the fulfillment of the law” or “God damn it, you’ve got to be kind” is bound to be shaped by all of the blindnesses and the assumptions of the people and the age that produced it. So every moral code will therefore have omissions and oversights, and will also include horrors that have no business being included. And just like in the MPPC’s list of “Don’ts,” those omissions and horrible admissions will wind up skewing even the good bits that might seem unrelated to them.

Whenever you question the “traditional morality” of any moral code that’s not aging well, you’ll be accused of lawless anarchy and antinomianism. “So you think anything goes” they say. They don’t mean it as a question, so they won’t wait for, or allow, an answer. And thus they’ll never understand the point.

The point isn’t that we should once and for all destroy all moral codes. The point is that we should perpetually be destroying them so that we can perpetually replace them.

Moral codes are things that perish with use. They have an appearance of wisdom in promoting self-imposed piety and severity, but they don’t age well. Test everything, hold onto the good.