David Watkins offers what I think is a helpful insight with a discussion of what he calls “The Weaponization of Religious Exemptions.”

This covers some of the same history we discussed here (in “Artificial Lemons“). After the Supreme Court allowed Oregon to refuse a religious exemption for a member of the Native American Church who used peyote in a religious ceremony, religious groups and civil rights advocates — everybody from the ACLU to the religious right — rallied in support of a legal remedy to reaffirm the right to such exemptions. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 was unanimously approved by the House of Representatives and passed 97-3 in the Senate.

Think about that for a moment. I’m not sure I can imagine the current House of Representatives unanimously approving anything, but that’s what happened with RFRA in 1993.

The rallying point for that law was what Watkins describes as a “classic example” of a religious exemption:

Here are some classic examples of requests for religious exemptions: permission to use otherwise illegal substances for religious ceremonies, such as the Smith plaintiffs and Peyote, Catholics and sacramental wine during Prohibition, Rastafari and marijuana; exemptions from zoning laws for the construction of Sukkahs and rules regarding the religious use of public property for the constructions of eruvs; exemption from mandatory military service, schooling requirements, or vaccinations; exemptions from incest laws (regarding Uncle/Niece marriages for some communities of Moroccan Jews); Native American religious groups seeking privileged access to sacred spaces on federally owned land; exemptions to Sunday closing laws for seventh-day Sabbatarians.

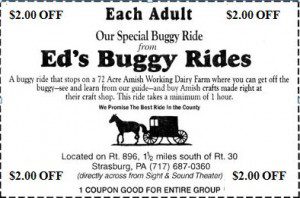

Those examples are not hypothetical — they come up all the time in American courts. Sitting here in Chester County, I’d add another prominent example: The Amish. Head west on U.S. 30 from here and you’ll soon encounter Amish carriages and Amish communities that enjoy a wide array of religious exemptions. Those exemptions are not controversial — not even for those stuck in traffic behind a buggy out in Gap — because, as Watkins says, “they are fundamentally defensive in character.”

I find some of these [classic examples] easy to support and others profoundly problematic, but they collectively share a common feature: they are fundamentally defensive in character. Their primary objective is to protect a practice or tradition or community, and little more. These exemptions are political but not in the sense that their exercise is directed toward the larger community in any concrete, meaningful sense. In these cases, the end sought in pursuing the exemption is, more or less, the exemption itself.

Bingo. “Fundamentally defensive in character.” That’s important.

I’m a strict-separationist Baptist kind of guy. That means, among other things, that I do not want to see any religious structures on government property. Public property is no place for sectarian religious structures.

But I also lived for many years inside the bounds of an eruv, and I do not believe that this eruv — by definition, a sectarian religious structure — violated the separation of church and state. I believe, rather, that allowing the presence of the eruv on public, government property was a Good Thing. It honored the important principle of the free exercise of religion. And it honored the important principle of not being assholes to minorities just because you’ve got them outnumbered.

If you’re not familiar with eruvs, they’re a kind of religious loophole that allows Orthodox Jewish communities to travel a bit on the Sabbath without breaking their religious laws. That requires some kind of boundary marker to enclose the area in which they are permitted to travel — ideally, an area large enough to include their synagogue and the local hospital. The enclosure needs to be physically bounded, and its physical boundary markers will often need to cross or rest on public property.

Part of the reason that eruvs are not a controversial religious exemption is because they are nearly invisible and completely non-intrusive. We’re talking about string or wire tracing existing utility lines along city streets. If you don’t know it’s there, you’ll never see it. (Even when you do know it’s there, it’s very hard to spot. But it’s kind of fun to try.) Accommodating an eruv is much easier for the rest of the community than accommodating the religious exemptions for our Amish neighbors here in Chester County.

But, as Watkins says, that’s not the main reason that an eruv is a classic example of an easily supported religious exemption. The main reason is that it is “fundamentally defensive in character.” It exists “to protect a practice or tradition or community, and little more.” Our Orthodox neighbors aren’t demanding that the rest of us abide by their religious laws forbidding carrying on the Sabbath. They’re simply asking the rest of us to allow them to do so by running a bit of unobtrusive string along public property. Yes, it’s sectarian string, but they’re not seeking a privilege that would give them some advantage over anyone else. They just want to do their thing and to survive. They want the right to extend their arm without hitting anyone else in the nose.

I don’t think that’s a threat to the separation of church and state.

Watkins then discusses what he calls “a kind of transitional case” — City of Boerne v. Flores. This was the 1997 case that overturned the RFRA law Congress had passed nearly unanimously four years earlier:

The exemption sought was to modify a church in a Historical District where such modifications were not permitted. While the exemption was clearly sought for the purpose of the exercise of religious activity, it wasn’t really a religious exemption per se — they wanted a bigger, more modern facility for more or less the general kind of reasons a private business or homeowner might have liked an exemption — accommodate more people, better amenities, etc. There was no connection between their status as a religious group and the nature of the particular exemption they were seeking; in essence they were arguing that the RFRA gives them license to avoid a law they found inconvenient.

That, Watkins says, is the first step toward “weaponized religious freedom” — “turning religious exemptions into a license for religious groups to evade general laws when inconvenient.” The next step is far worse:

But this is only a partially weaponized use of religious exemptions; they’re being used as a weapon to advance the church’s goals, but not striking against their political enemies. The quintessential case of a weaponized religious exemption is, of course, Hobby Lobby; Obamacare was to be the subject of a blitzkrieg, to be hit with any and every weapon imaginable, and that’s what the RFRA provided. Their efforts to make the claim appear credible could hardly be lazier or more half-assed. One possible check on weaponization, in a better and more decent society, could conceivably be a sense of embarrassment or shame; exposing one’s religious convictions as a cynical political tool to be wielded against one’s political enemies might be hoped to invoke enough embarrassment that it might be avoided, but we were well past that point. A remarkable document of this trend is this post from Patrick Deneen – fully, openly aware of the fundamental absurdity of Hobby Lobby’s case, cheering them on nonetheless. I mean, you’d think they’d at least have found a company owned by Catholics.

This weaponized use of religious exemptions has changed the context of the entire conversation that previously shaped our legal and neighborly accommodation of such exemptions. It is no longer about the classic examples of exemptions that are fundamentally defensive in character. This is an effort to use religious exemptions as an offensive weapon for political purposes that have nothing to do with the religious beliefs supposedly in question.

The goal of weaponized religious exemptions is not “to protect a practice or tradition or community” but to carve out privileges and advantages for some groups over others. And that, as Watkins says, changes everything:

The assumption on the right is that it’s liberals who’ve changed; we don’t support religious freedom like we did back in the 90’s. … [But] insofar as liberals changed their minds about the proper scope of religious exemptions, they didn’t do so in a vacuum, they changed their mind about it because the context we’re now in — facing an utterly shameless political movement that treats any conceivable political tool as fair game to achieve its political ends — is just simply not the kind of environment that fits well with an expansive approach to religious exemptions. The personal, faith-based nature of religious conviction makes it clearly inappropriate for the state to question the sincerity of the professed belief, even when that insincerity is obvious and barely concealed; which in turn makes exemptions easier to support in an environment where there’s some degree of trust that this process won’t be routinely abused. … We may have been something closer to that kind of society suited for expansive religious exemptions in the past, and we may someday be that kind of society at some point in the future, but it’s becoming difficult to deny we’re not such a society now.