So you’ve probably heard that an elected clerk in Rowan County, Kentucky, is being held for contempt of court because she has refused to issue marriage licenses following the Supreme Court’s ruling that the Constitution requires equal protection for same-sex couples.

This week, it was confirmed that this clerk, Kim Davis, has a rather complicated personal marital history including multiple divorces. It seems she has not lived up to the strict understanding of “biblical truth” on marriage that she has been trying to use her office to illegally impose on everyone else.

White evangelical culture warriors insist that this doesn’t make Davis guilty of “hypocrisy,” noting that she is a fairly recent convert to born-again white Christianity, and that her past failure to live up to this “biblical standard” dates back before her conversion. As Candida Moss summarizes:

In the past few weeks, Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis has been called both a hypocrite and a martyr.

Supporters of marriage equality have pointed out that thrice-divorced Davis seems to be in violation of Jesus’s instruction not to divorce. Even though Davis’s divorces took place before her baptism as an Apostolic Pentecostal, her Christian character has been called into question.

I broadly agree with Davis’ defenders who say that her conversion matters when it comes to the charge of her alleged “hypocrisy.” People have the right, and the capacity,* to change — to repent, be transformed, turn over a new leaf, or otherwise reinvent themselves, declaring “from now on ….” Such reinvention shouldn’t exempt them from any consequence or moral obligation to make amends for their prior behavior and identity, but it doesn’t make sense to equate every such repentance or change of mind with “hypocrisy.”**

And I’ll happily agree, or at least stipulate, that Davis’ conversion is genuine. The precise form of Apostolic Pentecostalism to which Davis converted is not clear, but any of the (recent, American, white) traditions that may refer to are, broadly, Baptist when it comes to the practice and doctrine of Baptism.

As far as the practice goes, that means immersion. You wade in the water and you go all the way under. None of this dainty, unbiblical “sprinkling” business, thankyouverymuch.

But don’t get distracted by the irrelevant sideshow of immersion vs. sprinkling. Christians periodically pretend that’s a big deal and they can get into heated arguments about it, but the truth is — looks furtively over both shoulders, leans in to whisper — it doesn’t really matter. Any disagreement about the logistics of Baptism is really just a proxy for the larger, far more meaningful disagreement over whether Christians should be baptized as infants or only later, as mature converts who freely choose, of their own accord, to be baptized.

Baptism by immersion is only meaningful because it signifies the underlying idea of “believer’s Baptism,” or “credobaptism.” That’s the idea that you get baptized when, and only when, you freely choose to do so. This is the idea of Baptism that makes Baptists Baptist.

Believer’s Baptism has all sorts of doctrinal and theological implications. It entails a wholly different form of ecclesiology — what Max Weber called the difference between a church and a sect. Those are significant and important and meaningful things, but they pale in comparison to its political implications.

Believer’s Baptism is, inescapably, a political act. Not just mildly so, either, it’s downright revolutionary.

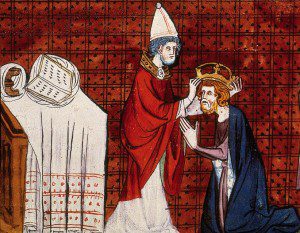

European history, for centuries, involved an ongoing struggle for sovereign power between popes and kings. From Charlemagne to Henry VIII to Napoleon, kings and emperors were constantly vying with popes and bishops over whose power was more absolute. The Protestant Reformation is inextricably tied up with that political struggle between civil and ecclesial power. For all of its theological causes and implications, the Reformation was shaped by that centuries-long context of kings vs. popes and princes vs. bishops. Theology weighed in on that struggle, sometimes favoring one side, sometimes the other.

Believer’s Baptism rejects that whole framework. Pope or King? Screw both of y’all. It says that Baptism — the act that marks one as a believer and a member of the church — isn’t a matter of political identity or ecclesial domain. It’s a matter of personal choice.*** That makes it a declaration of independence, dethroning kings and popes alike.

This was not always well-received by said kings and popes, to put it mildly. But after a few additional centuries of spastic and devastating religious violence, states and churches began to be a bit more receptive to this radical idea of individual religious liberty, or at least to the previously intolerable idea of religious toleration.

What all that means, in other words, is this: Believer’s Baptism requires the separation of church and state.

More than that: Believer’s Baptism defiantly asserts the separation of church and state. It declares and demands and demonstrates the separation of church and state.

Today, in 2015, millions of nominally “Baptist” Christians, and tens of millions more in Baptist-ish denominations that replicate the motions of believer’s Baptism by immersion, seem to have forgotten all of this. They have no idea what it is they are doing.

No idea at all.

This is why, all across America, people like Kim Davis or David Barton or Mike Huckabee can choose to be baptized. They can wade into the water where their pastor can ask them, publicly, to affirm that they take this step of their own choice and volition. And then they can go down into the water and be brought up again, reborn, while still having no understanding at all of what just happened.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* This footnote is for the Calvinists and/or 12-steppers who may be upset over that word “capacity.” Relax. We’re not getting into the source of this capacity here — or attempting to analyze whether it’s an intrinsic part of human nature or something wholly dependent on divine grace or any other “higher power.” That doesn’t affect the point here one way or another. The unchastened optimist who says that “People are intrinsically good and therefore people have the capacity to change” and the pessimistic Calvinist who says that “People are lost and incapable of salvation, but thanks to the grace of God, people have the capacity to change” both arrive at that same point: People have the capacity to change.

** Kim Davis’ personal history does not make her a hypocrite. It does, however, make her a graceless jerk.

Richard Beck doesn’t use that specific phrase, but he describes what I mean by that here:

When I do something wrong and feel guilty I’m trying to spend less time on how I’m such a screw up than on how, in light of my own failures, I should be more forgiving of the failures of others. If I’m such a screw up I should extend sympathy, empathy and compassion to others when they make mistakes. How can I judge others when I make similar or even worse mistakes?

My guilt is a trigger to extend grace to others.

Refusing to extend to others the same grace one depends on oneself isn’t precisely the same thing as hypocrisy, but it’s still a kindred form of self-serving moral duplicity. And that makes one a graceless jerk. Freely you have received, freely give.

*** Yes, yes, Calvinists. I see you. Go read that first footnote again.