This is a very local story, but it is not only a very local story. It has to do with a local church at the other end of our street — the same white evangelical mini-mega-church I visited on the Sunday before Election Day, where I heard a terrible concordance-pastiche sermon on the authority of the Bible, a weirdly perfunctory admonition to vote for God’s Own Party, and an abominable rendition of one of my favorite hymns (they stuck a bridge into the middle of “Be Thou My Vision,” and I’m still upset about that).

That pre-election service ended with the pastor urging his congregation to go and vote for God’s chosen candidate because evil liberals were poised to take away the religious liberty of real, true Christians:

“Our liberties are at stake,” the pastor continued. “Freedom, freedom to worship, the principles of the truths of this book” (here, again, he waggled the Bible he’d been praising earlier as King of Kings and Lord of Lords). He said he’d been to “other countries” where Christians were not free to worship, and had to “sneak in” to church. And he urged the congregation to vote because that was what was at stake in this election.

This recitation of the far-right, Chicken Little “religious liberty” argument sounds extreme when you read it here on the screen. And it is extreme. Here, after all, is the pastor of an American church standing before his congregation and informing them that their worship services may be cancelled, their faith outlawed, and their Bibles confiscated if the (unmentioned) wrong party wins in Tuesday’s election.

Well, thanks largely to churches like this one, Donald Trump narrowly won the state of Pennsylvania (with less than 50 percent of the vote here), and the narcissistic sexual predator this pastor believed was anointed by God to defend his congregation’s “religious liberty” is now the president of the United States. Worship services, therefore, have not been cancelled, Bibles have not been confiscated, and most pastors are not being thrown into prison.

But one pastor is headed to prison — a pastor from this very same church.

Jake Malone was sentenced last week to three to six years in state prison on charges of corruption of minors, institutional sexual assault, and endangering the welfare of children. The plea deal, struck to spare his victim from having to testify at a trial, involved dropping the original charges of rape and sexual assault, even if those charges better describe Malone’s crimes.

Malone moved to our town from Minnesota after he was hired as an assistant pastor at this evangelical church. He was recruited, invited, and relocated to serve there in a position of spiritual authority.

In defense of this church, once they realized what their newest pastor was up to, they did the right thing. They brought the victim to local police and immediately fired Malone (who briefly fled the country). The church cooperated with the legal investigation and didn’t attempt some kind of cover-up. They made it clear that it was unacceptable to have a sexual predator serving on their pastoral staff, even if they also, simultaneously, insisted that it was members’ Christian duty to elect another sexual predator to a four-year term as president.

And these things, I believe, are related — not just for this one local church, but for all the white evangelical churches like them across the state and across the country. Here’s how:

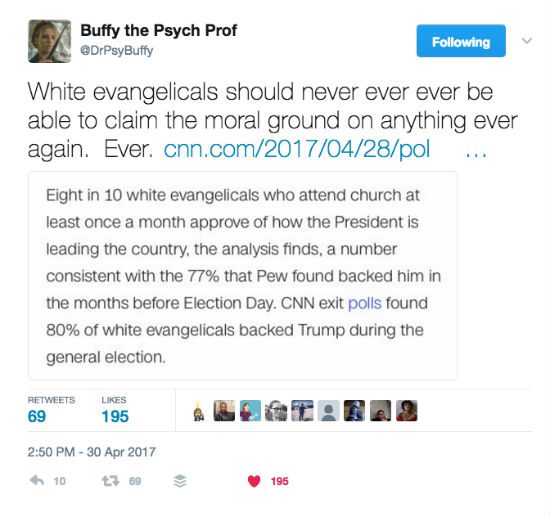

The tweet there mentions “the moral ground,” or as it’s often called, the moral high ground. And that idea is the crux of white evangelical identity. This is who and what white evangelicalism imagines itself to be: a moral authority. The moral authority. The arbiters and exemplars of what is right and good and true.

This is what revivalism is all about. What this world needs, perpetually, is another “Great Awakening” — an outpouring of revival and conversion in which everyone else becomes like us. That, ultimately, is the only hope for resolving all of society’s problems. That is what will make America great again, a shining city on a hill, etc. etc.

But there’s an anxiety-inducing recognition hovering around the edges of this great hope for revival. It comes from the half-acknowledged realization that everyone else already is just like us. Or, perhaps, that we are just like everyone else. We don’t seem any better than the rest of our neighbors. They don’t seem any worse than us. Our claim to be the keepers of morality, the occupiers of the moral high ground, doesn’t seem supported by any objective evidence of our purported moral superiority.

This is an existential problem. It gnaws at our identity, our sense of who we are. And it gets harder and harder to deal with every time our communities or our subculture is wracked with the kind of scandal that put that local pastor behind bars.

This anxiety became especially acute a generation ago during the Civil Rights Movement. Civil rights was the defining moral question of American life in the latter half of the 20th century. And white evangelicals, overwhelmingly, got it wrong. Prominent white evangelical leaders were among the most vocal opponents of the Civil Rights Movement, while millions more were simply indifferent, timid bystanders.

This was a moral test, and white evangelicalism failed it, spectacularly. It surrendered the moral high ground, forfeiting any claim to speak or to pose or to regard itself as the embodiment of moral good.

That was unbearable. White evangelicals watched, aghast, as the culture changed around them in the 1960s. They wanted to speak out from their presumed place of moral authority, condemning the sex, drugs and rock-n-roll that horrified them, but they had lost any claim to such moral authority by opposing the Civil Rights Movement (and by opposing the renewed struggle for women’s equality, the emerging environmental movement, the peace movement, the War on Poverty, and a host of other intrinsically moral questions they got wrong).

Again, this wasn’t just about power and influence. It was about identity. If white evangelicals could no longer credibly lay claim to the moral high ground, then they no longer knew who or what they were.

It took a while, but by the 1980s, white evangelicals found a strategy to redefine themselves by once again asserting their claim to be the possessors of the moral high ground and the arbiters of right and wrong. They gave up on imagining themselves to be better than everyone else and settled on redefining everyone else as worse than them. Those other people may have been morally right about civil rights and racial discrimination, and women’s equality, and poverty, and Vietnam, and pollution, but none of that mattered because those other people were also baby-killers. Satanic baby-killers.

Those people kill babies. That’s gotta be worse than us, right? So that makes us better than them. Sure, we may seem otherwise morally indistinct from most of our neighbors, and, yes, we sometimes may have to fire an assistant pastor for molesting a youth in his care. But we don’t kill babies. We’re against killing babies. And that means we have the moral high ground — always and forever.

This strategy proved enormously successful. It was so successful, in fact, that within a few short decades, white evangelicalism had completely reinvented itself and rewritten the essence of its religion around this central premise: We are the people who are against killing babies and therefore we are the people who possess the moral high ground.

This new identity has never been wholly satisfying. The illusion of moral superiority provided by this pretense has never quite wholly managed to still the nagging, semi-conscious recognition that it is only that — a pretense. But the dull, dim, background itch of such doubts is infinitely preferable to the unbearable crisis of identity it was adopted to patch over. This is who we must be, so this is who we are. We are good and righteous people who possess the moral high ground because we oppose the killing of babies. Our neighbors, therefore, are moral monsters and baby-killers.

Whether that seems likely or possible or not, it has to be true, and so we will go on saying it is.

See earlier: “This is what abortion politics is for”