Jeff Sharlet provides a history lesson of his own in his long, insightful review of Frances FitzGerald’s 700-page new history, The Evangelicals. Sharlet’s take is less critical than Randall Balmer’s (“Reading evangelical history with one eye closed”), but he offers some incisive thoughts on the gaps in FitzGerald’s account, which races through the early “Awakenings” to arrive at the rise of the religious right in the late 20th century.

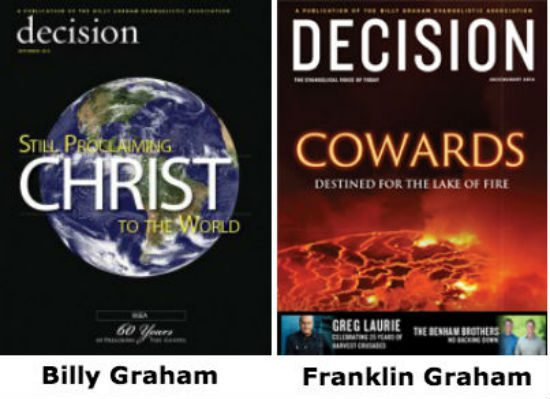

Those gaps help to illustrate why the lockstep partisanship of the politicized religious right is not a new thing in white evangelicalism. Perhaps even, as Christopher Stroop recently remarked on Twitter, why “Sadly, Billy Graham people have always been Franklin Graham people.”

Filling in the gaps in that long history and long pedigree is important, because in tracing what hasn’t changed over the years, Sharlet is better able to focus on what has changed — on the one thing that’s new and unprecedented in the religious right:

Conservative evangelicalism has been an essential part of American politics going back much further than 1980. International Christian Leadership was the Christian Coalition of its day, less visible mainly because its aesthetic was establishmentarian. By contrast, Robertson and his peers, following the example of Reagan, emphasized the populist aesthetic of their tradition — even as they encouraged their followers to cling ever more fiercely to the corporate economics that had once been more of a concern of the men who paid for revivals than for the men and women who attended them.

What did change with the rise of the Christian Right was its emphasis on the politics of the body. Not so much actual bodies as imagined ones: particularly those destroyed by what some evangelicals came to call the “holocaust” of abortion. Towards the end of The Evangelicals, FitzGerald pays special attention to the case of Terri Schiavo, whose brain-dead body became a cause célèbre for evangelicals in the 2000s. The why of this turn toward the body — beyond the past interventions of fundamentalist intellectuals like Francis Schaeffer and Chuck Colson — remains an important question in evangelical history. FitzGerald would certainly be excused for failing to come to any strong conclusions. But she explores neither the significance of Schiavo’s fate in the lives of believers, nor the ways in which, for evangelical leaders, it was as much a stylistic change as a substantive one, a substitution of one jeremiad of cultural collapse for another.

This is key: “The why of this turn toward the body … remains an important question in evangelical history.” And thus it is an important question regarding the white evangelical present, and any white evangelical future.

And, because of the vital role that politicized white evangelicalism has come to play in American politics, it remains an important question for the entire nation.

Sharlet’s term for this New Thing strives to comprehend within it all the various peripheries of the religious right’s “emphasis on the politics of the body.” That term is spacious enough to include all the varieties of genital politics that have obsessed the culture warriors of the religious right — anti-feminism, homosexuality, its very recent shift to opposing birth control — while still also encompassing its longstanding fear of black bodies, of the lives it cannot bring itself to agree matter. But it’s also accurate to suggest, as he does, that this “turn toward the body” involves one thing above everything else in particular: “what some evangelicals came to call the ‘holocaust’ of abortion.”

That’s the New Thing. Today, it is the central and essential component of white evangelical identity — the paramount defining characteristic of the culture, doctrine, theology, piety and practice of this otherwise frustratingly amorphous branch of American Christianity. It is the one subject, above all others, on which no dissent is permitted. And that wasn’t the case 50 years ago. Or 40 years ago. It is an idea, as I have written before, that is younger than the Happy Meal. And this new idea was embraced so enthusiastically that we’ve re-written our English translations of the Bible just to accommodate it.

How did that happen? Why did that happen?

Those are not quite the same question. Sharlet acknowledges that by suggesting that the answers lie elsewhere than in “the past interventions of fundamentalist intellectuals like Francis Schaeffer.” I’m old enough to remember sitting in our darkened church sanctuary, watching Schaeffer walk through plastic dolls strewn along the shore of the Dead Sea as he explained to us that we could become the unambiguously virtuous heroes of an unambiguously virtuous holy war. I am old enough to remember the change, the before and after of it, and so I can remember the role that Schaeffer’s rhetoric played in that change — his role in the how of it.

But the why of it is not the same thing. The why of this turn toward the body involves far more than that. It’s not just about the causes of this change, but of its functions — not just how it was imparted, but of how and why it was received. And it is also, subsequently, about the consequences of those functions, which have been spiritually disastrous for evangelicalism and measurably disastrous for American society.

I don’t think we can begin to understand any of that without exploring the several functions that this transformation of evangelical religion plays. Those functions have become the emotional and spiritual cornerstones of evangelical identity, which makes this subject a matter of existential significance. They’re why it’s generally impossible to have a debate or an argument about the legality/criminality of abortion in America, why it’s nearly impossible even to achieve disagreement on the subject. Identity is at stake, which means, in a sense, that everything is at stake.

We can approach that head-on, with the ferocity of the Sermon on the Mount, saying “Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.” Or we can approach it with delicacy and grace, taking care not to break a bruised reed or to quench a smoldering wick. But either way, we need to approach it. The why of this newfound, re-defining “emphasis on the politics of the body” — this pre-eminence of the politics of abortion — is too important to avoid. We need to identify and to understand the functions it plays, the needs it addresses, the spiritual and practical effects it produces.