The “Great Commission” objection we talked about in the previous post is something that may be difficult to appreciate for those who have never been a part of the white evangelical subculture in America. But for anyone who was within that subculture during, say, the years of Billy Graham’s vitality, it’s a very familiar phenomenon.

The folks at evangelical relief and development agencies know exactly what I’m talking about here. World Vision spent decades patiently responding to the concern that their work distributing food, digging wells, building schools or providing other humanitarian aid was a dubious potential distraction from the “more important” Christian duty of proclaiming the gospel. It’s not that white evangelicals objected to any of those corporal works of mercy per se — they accepted that such things were nice and probably even intrinsically good — but that they worried that such temporal concerns of helping bodies could come to overshadow the eternal concern of saving souls. So such works were often viewed suspiciously — as possibly permissible, but only so long as they were done with the clear intention of preparing those helped to then be given the message of the gospel. Relief and development work, or “charity” more generally, was condoned only if it was explicitly subservient to the proclamation of the gospel — a means to that end and not something regarded or conducted as an end in itself.

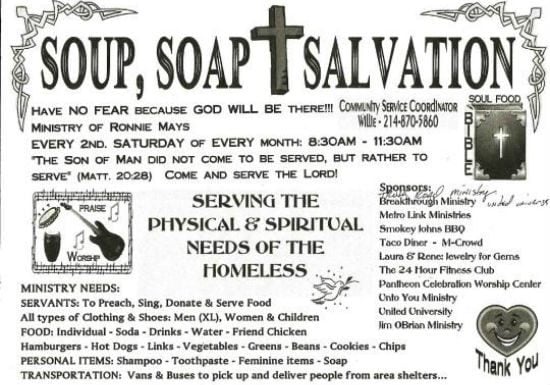

Every medical missionary commissioned by any white evangelical mission board has had to contend with this Great Commission objection. Every mission agency that built hospitals or schools had to have an answer to it — an explanation for why they were doing that rather than building churches. Talk to anyone from Compassion International or any other such child-sponsorship organization, or to anyone from the Salvation Army or any Gospel Rescue Mission shelter and they will have a ready response — rehearsed and practiced for decades — to this very concern, which they’ve heard more times than they could ever count.

We don’t need to get into the substance of such responses here. That’s not my point. Nor am I bringing this up in order to critique the other-worldly distortion of the gospel that elevates proselytizing above love and justice. (Here I’ll just sub-contract that discussion to Sister Maria and Brother Nicely.) The point here is simply that this was once a thing. It was such a Big Thing, in fact, that it was one of the defining characteristics of white evangelical culture, theology and piety.

We can go back and read through some of the white evangelical debate over segregation and integration in the 1950s and 1960s to see how this concern shaped “both sides” of that discussion. Hard-core defenders of segregation like Billy Graham’s father-in-law, L. Nelson Bell, argued against the Civil Rights Movement because, they said, it was a dangerous distraction from Christians’ paramount duty to preach the gospel. Other white evangelicals, like Billy himself, sought a somewhat softer tone, rejecting such a full-on defense of segregation because that, they argued, might itself become a distraction from the ethereal gospel-proclamation that ought to be Christians’ primary concern.

In my own lifetime, I remember this Great Commission objection being the initial, reflexive white evangelical response to folks like Francis Schaeffer and Jerry Falwell when, in the early 1980s, they first introduced the new idea that we, as white evangelicals, should take up the cause of opposition to legal abortion. That was how we responded to the temporal concerns of the Moral Majority’s political agenda because that was how responded to any temporal concern. The particular substance of all such things didn’t matter, what mattered was that we understood ourselves to be people who must, above all else, be going into all the world and preaching the gospel. Anything other than that, no matter how worthy it may seem on its own, was met with skepticism that it could sap the energy and monomaniacal attention we were meant to be giving to this matter of utmost importance.

It seems to me that this Great Commission objection has waned in the 21st century. I would count that as a positive development, except that I fear it has simply been replaced by something else that’s even worse. Sixty years ago and 30 years ago, white evangelicals instinctively evaluated every cause or “issue” by weighing it against the paramount concern of proclamation evangelism. Today they seem to demonstrate that same instinct, but it’s no longer proclamation evangelism that they worry may be undermined — it’s opposition to legal abortion.

I’m seeing the same reflexive “Maybe, but …” response, but instead of “Maybe digging wells is worthwhile, but it must not be permitted to undermine the priority of preaching the gospel” it now seems to be “Maybe digging wells is worthwhile, but it must not be permitted to undermine our commitment to a firm pro-life stance.”

What that means, in practice, is what it was designed to mean. It means that white evangelicals may be permitted, conditionally, to consider some other, tangential causes — “creation care,” or “racial reconciliation,” or “human trafficking,” or whatever you like — but only to the extent that these things do not distract from the absolute, paramount duty white evangelicals have to support the election of Republicans to every branch and every level of government in the hopes that they will eventually pack the Supreme Court with enough anti-abortion justices to overturn Roe v. Wade.

That’s a starkly blunt way of putting it, but that is the essence of the objection. All those other causes, you see, may be laudable and commendable in and of themselves, but they’re all also vaguely liberal-seeming. And it’s dangerous to permit ourselves to have too much sympathy for liberal-ish causes because that might undermine our resolve to vote for the kind of anti-liberals we need to support in order to fulfill our paramount obligation of criminalizing abortion.

It’s possible I’m reading this wrong — that my perception of the waning and replacement of the former Great Commission objection is an illusion produced by the changing of my own vantage-point. Back in the ’90s, after all, I was working for Evangelicals for Social Action — a job that put me constantly in the path of the old Great Commission objection. Encountering that and countering it was essentially what I did for a living. These days I’ve been farewelled to the outskirts of that subculture, so I’m no longer immersed in it as thoroughly as I was and I may be prone to bad sample errors based on interactions that involve too many of the kind of vocal white-evangelical culture-warriors who predominate in online discussions and social media. Maybe the voices I’m hearing the most from these days — while numerous and popular — are not as representative as they seem.

But I still think there’s something to this. It certainly seems to me like the new objection has mostly replaced the old one. It seems like the instinctual white evangelical response of “Maybe, but it mustn’t be allowed to distract us from our pre-eminent duty to proclaim the gospel” has largely been replaced with “Maybe, but it mustn’t be allowed to distract us from our pre-eminent duty to be ‘pro-life.'”

I started this post by saying that the pervasiveness of the old Great Commission objection was something that might be difficult to convey to people who have never been part of the white evangelical subculture. That’s understandable. What’s puzzling to me is the way it’s gradual replacement by the anti-abortion objection has gone largely unnoticed by those within that subculture. It’s a huge, seismic change — a substitution of what it regards as its foremost obligation and its defining characteristic.

Such a monumental shift seems like something worth noticing.