Calls to abolish ICE are being decried by the Fox News crowd as “radical.” That’s odd, considering that the agency hasn’t even been around as long as CSI: Miami.

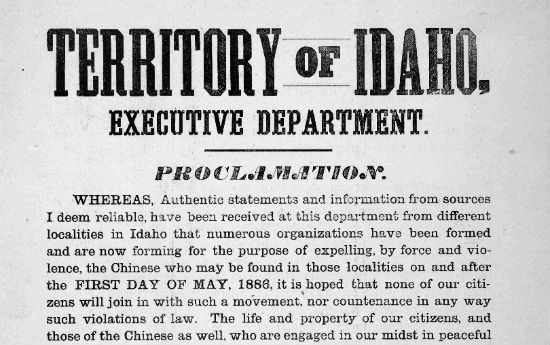

For a bit of historical context, here’s the 19th-century equivalent to “Abolish ICE” — an official proclamation from the territory of Idaho, issued April 27. 1886:

WHEREAS, Authentic statements and information from sources I deem reliable have been received at this department from different localities in Idaho that numerous organizations have been formed and are forming for the purpose of expelling, by force and violence, the Chinese who may be found in those localities on and after the first day of May, 1886, it is hoped that none of our citizens will join in with such a movement, nor countenance in any way such violations of law. The life and property of our citizens, and those of the Chinese as well, who are engaged in our midst in peaceful occupations, are entitled to and must receive the equal protection of the laws of our Territory.

I do, therefore, admonish the people in every portion of Idaho to oppose in every lawful way the institution of such riotous proceedings and mob violence. And I warn those persons, organizations and committees having in view the forcible expulsion of the Chinese, or any other persons now pursuing their peaceful labor, against such acts of violence, with the assurance that the law will hold those who may engage in such deeds responsible, individually and collectively, for the results of their acts. And I particularly notify and call on the Sheriffs of the Counties and the Officers of the law to use every precaution to prevent all riotous demonstration for such objects, and if unable to maintain the peace and majesty of the law, to call on every male citizen to assist you, recording the name of every man who refuses you assistance, or who are rioters, for future prosecution.

The territorial governor who issued that proclamation, Edward A. Stevenson, was not some radical leftist champion of immigrants, nor was he one of those rare American Christians who chose the teachings of his faith rather than white supremacy. The year before, Stevenson had defended the lynching of five Chinese miners, saying the men were probably guilty due to their “filthy habits.”

Nor was he some anti-federal radical looking to pick a fight with Congress — Stevenson’s whole career in Idaho was focused on ingratiating the territory to Washington in the hopes of gaining statehood.

But Stevenson understood the 14th Amendment: “… nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” He recognized that due process and equal protection were the sacred right of “any person” within his jurisdiction.

The adjective we use for this now — for jurisdictions committed to actually upholding the lawful rights guaranteed by the 14th Amendment — is “sanctuary.” That’s the term we use for those jurisdictions who recognize that due process and equal protections accord to persons — not merely to citizens, or to Herrenvolk.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had recently declared Chinese residents to be non-citizens, abruptly creating the vicious new concept of “illegal immigrants.” That law was both a result of and the cause of racist mob violence targeting Chinese residents of America. Dozens of Chinese residents in the neighboring territory of Wyoming had been slaughtered and burned in their homes in the Rock Springs Massacre a few months earlier — with lawless impunity that had inspired a wave of similar violence throughout the region. Local militias — the Klan and its many imitators — were planning something in Idaho.

This gathering “deportation force” might have the tacit, or even the explicit, support of Congress, but Stevenson wasn’t going to allow the 1880s equivalent of ICE to forcibly deny the constitutional rights of persons within his jurisdiction. So he issued his unambiguous “warning” to “those persons, organizations and committees having in view the forcible expulsion of the Chinese, or any other persons now pursuing their peaceful labor.”

He warned them that they would be arrested.

And then he charged all local law enforcement to carry out those arrests, and to deputize every man in Idaho to assist in that — and further to arrest and prosecute anyone who refused to aid in the arrest of “those persons, organizations and committees having in view the forcible expulsion of the Chinese.”

Stevenson there was referring mainly to the kind of violent mobs that had formed in Rock Springs, Wyoming. But in 1886 “those persons, organizations and committees having in view the forcible expulsion of the Chinese” also very much included Congress itself — and anybody Congress sent in an attempt to enforce its mandated forcible expulsion of the recently declared “illegals.”

In 1886, of course, Congress didn’t have a formal version of ICE to do this. What they had instead were loosely organized, lawless, unsupervised mobs of violent racists gleaned from the dregs of society and sent forth with no training, no oversight, no restric–

Yeah, OK. That’s ICE in a nutshell. Only meaningful difference is ICE has better equipment and fancier uniforms.

In 1886, the mainstream, not-at-all-radical response from a mainstream, corporate-friendly, not-at-all-radical territorial governor was not nearly as restrained and moderate as “abolish ICE.” He warned, rather, that he would arrest ICE. Heck, he would arrest any man in Idaho who refused to participate in the arrest of ICE.

So, no, I do not buy that calling for the cancellation of the failed 16-year experiment of “ICE” is in any way radical. “Abolish ICE” is a decent, prudent, necessary, restrained, mainstream and thoroughly moderate proposal.

I’ll grant that Stevenson’s alternative — “arrest ICE” — might be somewhat closer to a “radical” approach. But that doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea either.