Critics of “political correctness” often seem to object to simple kindness or courtesy, to the expectation that one should try to cause no harm. This is really rather an old-school expectation, connected with ideas about magnanimity and generosity. John Cardinal Newman defined a gentleman as one who will never willingly cause pain: by that definition, it would seem that the refusal to use politically correct language would be the act not of a gentleman, but of a lout (while I’m being Victorian about it).

Sometimes the criticism stems from ignorance of the fact that social norms change, language itself changes, and we have new rules of societally correct interaction now. Maybe people would be less wary if we termed the effort to give people the pronouns or descriptors they ask for as “social” rather than “political” correctness. Or perhaps they wouldn’t care. But at any rate, it would call into question the presumption that there is anything praiseworthy or courageous in willful rudeness. Congratulations, you won’t use the correct term. I suppose you chew with your mouth open, too, just to assert your independence over the tyranny of table manners?

But the comparison to etiquette only goes so far. Inasmuch as political correctness is associated not just with social propriety, and the refusal to cause pain – but also with social justice, and the determination to do good – it may veer far away from etiquette. It may have to.

Because, for all that the gentleman never willingly causes pain, rules of discourse have often been set in place not to ensure justice, but to hide injustice, or to protect existing power-structures.

A meme on my Facebook feed today reminded me of this: it was an image of a page from Austin Channing Brown’s I’m Still Here, shared by Rachel Held Evans, with the comment that “Just the ‘Nice White People’ chapter in #imstillhere is worth the price of the book, y’all.” The underlined quotation from Brown:

When you believe niceness disproves the presence of racism, it’s easy to start believing bigotry is rare, and that the label racist should be applied only to mean-spirited, intentional acts of discrimination. The problem with this framework – besides being a gross understanding of how racism operates in systems and structures enabled by nice people – is that it obligates me to be nice in return, rather than truthful. I am expected to come closer to the racists. Be nicer to them. Coddle them.

Reading this, I was hit by a series of waves of recognition, of the many times this niceness mechanism had functioned to silence me.

Every time people have responded with more anger against those who call out racism, than against racism itself.

Every time I’ve been assured someone couldn’t possibly be a racist, because “she’s so nice.”

Every time someone has invited me, implicitly, into an assumption of shared racial prejudice – invited me kindly, warmly, as though we were in for a fun time together. If I reject their invitation, does that make me cold? Mean?

Every time the rule “don’t talk religion or politics!” has obliged me to nod and smile rather than say “actually, there’s no such thing as reverse racism” or, “yes, cultural appropriation is real,” or “if you think it’s bad to be accused of racism once, imagine what it’s like to be the victim of racism every day of your life.” Saying these things means sticking out as the social pustule, the one making things unpleasant, raining on the happy white-person parade. It means not getting invited back.

This is true of other issues, too. The environment, for instance. It sucks that we’re all eventually going to smother in heaps of rubbish, but let’s not say anything about the conspicuous consumption of well-off westerners, because it will make everyone uncomfortable. And why spoil the fun of our little white children, by telling them that the toy they want was probably made by enslaved black children?

The price of justice for the oppressed is set so low, it is valued less than a moment’s comfort for the powerful. And our laws about civility often end up preserving this imbalance. “Don’t talk politics!” is a social privilege for those who can pretend politics doesn’t affect other people, often grievously.

We need to think more carefully, maybe, about how to differentiate between social norms that preserve the powerful from discomfort, on one hand, and social obligations to protect the vulnerable from genuine injustice, on the other. It might be a good idea to get I’m Still Here, or talk to people of color about their experiences of being silenced by polite white culture, too, because those of us who benefit from etiquette might have greater difficulty parsing it out.

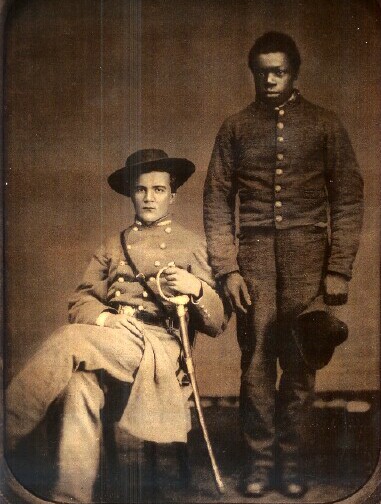

Image credit: Petersburg Express / Black Confederates