On May 12, I was honored to be a featured writer at Italian American Literati 2018 an event hosted by Casa Italia in Stone Park, Chicago. The library is dedicated to documenting the history of Italian-American immigration to Chicago, which began in the 1880s. The Casa Italia Library is a real gem for historians, sociologists and cultural anthropologists researching the immigrant experience in America. The annual IA Literati event gathers together contemporary authors writing from their own experiences as immigrants or as members of immigrant families. The work ranged from literary fiction (Where My Body Ends and the World Begins, by Tony Romano); romance set in ancient Rome (Quest for the Crown of Thorns, by Cynthia Ripley Miller); health and well-being books from Dr. Bruno Curtis and nutritionist Carol D’Anca; a new cookbook from Chicago restauranteur, John Coletta (the book is Risotto, the restaurant is Quartino); a book of watercolors of Chicago’s Italian neighborhoods by artist Anne Marie Cina; and poetry from Adam Sedia, who is related to an Italian poet writing during the Risorgimento in Italy in the 1850s. That’s just a sample of the genres and topics represented in the event line-up.

So what was I doing there? Taking it all in, for one thing! Though I’m not a native Chicagoan, I am the granddaughter of Italian immigrants who settled in Newark, NJ at the turn of the twentieth century. Dominic Candeloro and Anna Weiss, the event organizers, graciously included me on the program. I was delighted for the opportunity to talk about two geniuses of the twentieth century who have had a profound influence on my life and work. What follows is the text of my talk about these two giants and the surprising connections between them.

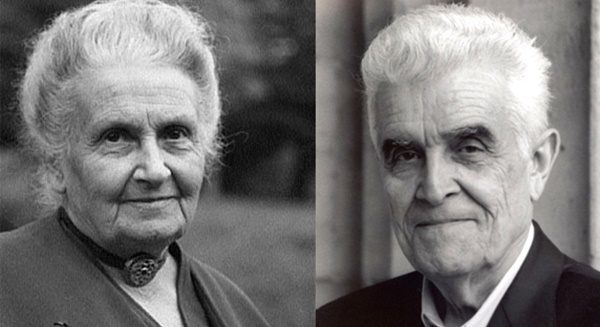

What do René Girard and Maria Montessori Have in Common? More Than You Think!

It is a real honor to be included in today’s event at Casa Italia. I’d like to talk about two projects of mine and how they are connected. One I completed ten years ago, my nonfiction book The Wicked Truth: When Good People Do Bad Things about the Broadway musical Wicked. If you’ve seen the musical you know tells the story of the Wizard of Oz from the wicked witch’s point of view. In my book, I use the musical to give an introduction to mimetic theory, a revolutionary explanation of human behavior that has challenged everything I thought I knew about good and evil. The theory was developed by René Girard, one of the most brilliant thinkers of the late twentieth century. Girard’s thought is counter-intuitive and reading him feels a bit like having your foundation unmoored by a tornado! Two insights of his radically alter the way we think about conflict and peace. First, he convincingly demonstrates that we come into conflict not because of differences but because of what we have in common. We fight because our desires have converged on an object neither side is willing to share. In other words, our enemies are mirror images of our desires, more like us than we are comfortable admitting. And second, Girard insists that the greatest obstacle to peace is not evil or wicked people, though they surely exist. The greatest obstacle is the faith that good people have in the goodness of our own violence. He offers brilliant insights into the dynamic of scapegoating by which good people convince themselves that they have identified the wickedest witch of all, and are therefore justified in killing her. To achieve peace, Girard insisted, good people must learn to recognize just how often our enemies are our scapegoats.

Now I had long been a fan of the 1939 movie, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and I thrilled at the end when a good little girl, like me, triumphed over the terrible witch. But Girard taught me that this story of good conquering evil is a classic example of what he called a myth of good violence. In The Wicked Truth, I contrast the movie with Wicked the musical which does what no good myth would ever do: question the necessity of killing the witch. You may be surprised to learn that there are plenty of clues in the movie that cast doubt on the goodness of Dorothy and her friends, clues the myth of good violence keeps us from taking seriously.

For example, remember that when we first meet the Wicked Witch of the West, her sister has been killed by Dorothy’s falling house. All that’s left of the poor woman is her shoes. They end up on Dorothy’s feet and the witch wants them for herself. When Dorothy refuses to give them up, on the advice of the counsel of the good witch Glinda, the wicked witch is enraged. She vows to get the shoes even if she has to kill Dorothy to get what she wants. The movie asks us to accept her embrace of violence as evidence of her wickedness for if she succeeds in killing Dorothy, we would call it murder.

With that in mind, let’s skip ahead to a pivotal scene in which Dorothy and her friends mirror the witch’s violence almost exactly. It’s when they have their audience with the Wizard. Each of them wants something as desperately as the witch wants the shoes. Dorothy wants to go home, the Scarecrow wants a brain, the Tin Man a heart and the Cowardly Lion wants courage. What does the Wizard tell them they must do to get what they want? Bring him the broomstick of the Wicked Witch of the West. They understand immediately that they will have to kill the witch to get her broomstick – but that doesn’t deter them. Like the witch, they are willing to kill to get what they want but because she is wicked and they are good, neither they nor we question the morality of this particular murder. Now let’s skip to the end of the movie. Remember that when they bring the broomstick to the Wizard and demand he make their dreams come true, he tells them that have always had what they so desperately desired. But we somehow manage to ignore this rather blatant evidence that Dorothy and friends have killed someone for no good reason, and so we join the Ozians’ celebration of the witch’s death without any moral misgivings. The movie ends with good people never understanding that in the name of goodness they have done a very bad thing. The wicked truth is that when good people use violence to achieve our ends we must give up our claim to being good.

My other project seems on the surface to be very different from The Wicked Truth; it’s my work in progress, a play inspired by the life and work of the great Italian educator, Dr. Maria Montessori called The Miracle of San Lorenzo. But like Girard, Montessori’s work has direct application to the pursuit of peace. In 1907 she began an experiment with a group of fifty, three to six-year-olds who were running wild and vandalizing their low-income housing project in San Lorenzo, a slum district of Rome. But under the influence of Montessori’s carefully prepared learning environments, these impoverished children from mostly illiterate families became calm, peaceful, and capable of intense, almost meditative, concentration. When they began to read and write with very little instruction, it shocked Dr. Montessori as much as it shocked the world and her little experiment in San Lorenzo became a pilgrimage site for those interested in unleashing as yet untapped human potential. She realized that by shifting the method of teaching from talking at children to observing and supporting what the children were doing spontaneously, a new type of humanity would emerge, one that was less prone to violence and scapegoating.

Maria Montessori died in 1952, just as Rene Girard’s career was beginning, but in many ways her discovery is an application of Girard’s mimetic theory to education. They were both geniuses, boldly proposing theories that challenged conventional thinking and they scandalized the world in large part because they were scientists who made no secret of their faith. They shared a conviction that their discoveries were not of their own making but were given to them in flashes of insight for a divine purpose. As Dr. Montessori quips at one point in my play, “My method is scientific, my faith is in God.” Both were extraordinary scientists who refused to scapegoat religion.

I’d like to introduce you to Dr. Montessori with a few excerpts from the play. In them she is addressing the attendees of the first international training course in her method held in Rome in 1913. She directly addresses the audience as if they were those first student teachers, so I invite you to imagine yourselves attending the lectures of this world-famous innovator as she shares her discovery of the secret inner life of children with you.

The Miracle of San Lorenzo, Act 2

MARIA MONTESSORI

It is tempting to be sentimental about children but sentiment will blind you to the real child. You must cultivate love not sentiment for it is love that desires to be drawn into exquisite knowledge of the beloved. People say they love the stars, the flowers, music. But that is mere sentiment. How few of them quiet their ego long enough to know a star, to contemplate a flower, or learn the inner secret of music! May I tell you something? To the world I am an accomplished woman replete with fame and honor. Indeed, when I was young I desired my own glory most of all. But I did not find joy until I found the child. When I am with children I am nobody, and the greatest privilege I have when I approach them is being able to forget that I even exist, for this has enabled me to see things that one would miss if one were somebody – little things, simple but very precious truths.

One day early in our experiment at San Lorenzo, I had entered the classroom holding in my arms a four-month-old baby girl that I had taken from her mother in the courtyard. She was swaddled as is the custom and her face was full and rosy and she was so still that her silence impressed me greatly. The children gathered around me, naturally interested to see what I was holding so carefully in my arms. “Do you hear?” I asked them. “Listen! She is not making a sound. None of you could do as well!” I said it as a little joke, but to my surprise the children looked at me intensely, so I continued to draw their attention to the silence. “Notice how soft her breath is. None of you could breathe as silently as she.” They took my comment to heart! They became motionless and held their breath. It was an impressive silence! Little by little we could hear other slight sounds that often went unnoticed – the far-off chirping of a bird, a drip of water hitting the floor. When I thought they had been silent for as long as was possible for them, I sent them back to their work. But they did not move! Not until I promised that we would practice silence again tomorrow did they return to their activities. Who were these children? Capable of such an advanced spiritual discipline. I remembered the words of Christ, the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.

I end the play with these words from Dr. Montessori.

MARIA MONTESSORI

Congratulations, dear students! You have completed your first month of training, a good time for a story about Saint Lawrence, the great martyr of the early church for whom the San Lorenzo district is named. In the third century, the emperor Valerian ordered all bishops, priests, and deacons to be put to death.

The bishop of Rome, Sixtus the second, was found murdered in the catacombs along with six of his seven deacons. The only remaining deacon was Saint Lawrence. The next day, he was arrested though not immediately killed. Because the Romans knew that he was the deacon in charge of the treasury and distributing the church’s offerings to the poor. They demanded he bring them all the treasures of the church if he wanted to avoid the fate of his brethren. Dear Lawrence did return in three days’ time but not with the money from the treasury. No, he arrived leading a procession of the poor and sick of Rome! These are the treasures of the church, he said, and for his faith he was tortured and burned to death on a gridiron.

Friends, you have been called to a great redeeming work, and though you will not be roasted on a gridiron you will be misunderstood by the world. Those who store up earthly treasures for themselves will never recognize the value buried within the hearts of little children. They wait in hope that we will swallow our pride to be led by them into the future God is preparing for us all. Love does not coerce or demand, it waits in patient silence to be received. Now go, learn from the children, and spread the word among all the earth that God has not withdrawn from the world or hidden his face from us. The age of peace has begun and you are its missionaries.

Images: Maria Montessori, Wikipedia. Rene Girard, courtesy of Imitatio.

Stay in the loop! Like Teaching Nonviolent Atonement on Facebook!