(Author’s Note – I wrote this post a couple of years back, in my second year of seminary. Having had some time to think on theology a bit more since initially writing it, I’ve tweaked a few elements and wanted to re-post it hear in revised form. It is an incredibly important topic and one I think deserves a place here. -TSB)

Is Belief in the Trinity Important for the Christian Faith and Life?

I had a friend of mine ask me the other day whether or not I thought the doctrine of the Trinity was integral to being a truly devoted and faithful Christian. While I cannot be sure, I believe another question that might have been lying behind this, was whether or not belief in the Trinity is necessary for salvation.

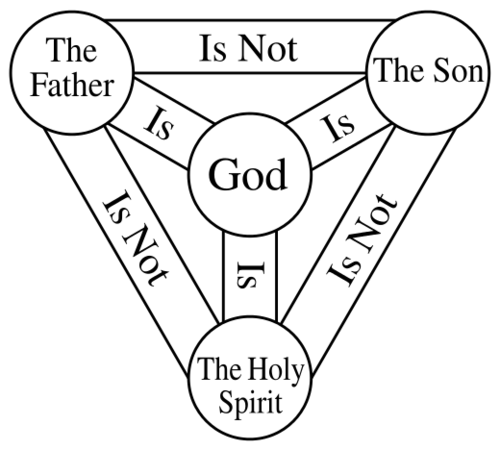

Regarding that question, yes I do firmly hold that a belief in, and affirmation of, the Trinity—that is, that God exists eternally as three persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in one infinite, simple, and uncreated essence—is integral to being a faithful and fully devoted Christian. There are many reasons for this, but for brevity’s sake I will simply lay out two of what I consider to be the most important.

The Shield of the Trinity (Scutum Fidei)

1.) The New Testament Triune Formulae

The New Testament (and many parts of the Old Testament) is permeated with both explicit and implicit references to the Triune Godhead. Matthew ends his Gospel with the Risen Jesus’s commission to His disciples to go out into all the world, proclaiming the good news, making disciples, and baptizing them in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. (Matt. 28:19). Likewise in all three of the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke) after Jesus has been baptized by John the Baptist, God the Father speaks from heaven, as the Holy Spirit—in the form of a dove—rests upon Jesus and the Father declares him to be his beloved Son (Mark 1:10-11; Matt. 3:16-17, Lk. 3:21-22).

The Gospels are not alone in this regard. Paul speaks of the three persons of the Trinity as acting together in unity on multiple occasions. For example in his epistle to the church in Galatia he writes:

“But when the fullness of the time came, God sent forth His Son, born of a woman, born under the Law, so that He might redeem those who were under the Law, that we might receive the adoption as sons. Because you are sons, God has sent forth the Spirit of His Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” Therefore you are no longer a slave, but a son; and if a son, then an heir through God.” (Gal. 4:4-7 NASB)

Further still, in concluding his second epistle to the church in Corinth, Paul concludes the discourse with a Trinitarian prayer:

“The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit, be with you all.” (2 Cor. 13:14)

The original Greek text is even more illuminating in this short prayer because the exact wording for “God” which Paul uses is τοῦ θεοῦ (tou theou), literally, “of the God.” Whenever Paul uses that wording (the Greek direct article with theos), he almost always uses it in specific reference to God the Father, as opposed to the Son and the Spirit, which he uses different names for. Thus, in this short closing prayer—the formula of which Paul likely received from someone else, possibly even one of the Twelve Apostles—we can see in the earliest strata of historical evidence available to us an already existing and established Triune formula.

I of course could list many other references in the Johannine corpus and the Petrine corpus, as well as the Old Testament, but these few will suffice for now.

2.) God’s Eternal Existence as Love

One of my favorite verses in the whole Bible is 1 John 4:8. There, John, in the context of exhorting his audience to love another in Christian community, writes:

“The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love.”

Those last three words are some of the most important ever penned in human history. While many of the pagan gods could show favor or affection (usually only to the most devout worshipers; which usually meant the Greco-Roman elite and powerful), their existence was not defined by love; indeed most were quite spiteful and morally destitute. As New Testament scholar Larry Hurtado notes, the Christian God was considered downright strange in the ancient world:

“But there was a still more unusual and, in the eyes of pagan sophisticates, outlandish Christian notion: the one, true, august God who transcended all things and had no need of anything, nevertheless, had deigned to create this world and, a still more remarkable notion, also now actively sought redemption and reconciliation of individuals. And what was the proffered reason for this remarkable redemptive purpose? God loves the world and humanity!”[1]

Coming back to 1 John 4:8, we see that John is not referring to one of the lesser pagan gods, but “the God,” the Creator God, the God who is the Ground of Being and Existence Himself! And this God is love. That is to say, He exists eternally in a state of self-giving, other-oriented, loving relationality. God has never not been loving toward another and He will never cease to be loving toward another.

But the created world is finite. Everything other than God Himself has not existed from all eternity. Even the greatest of angelic beings had a beginning. So how then can God be eternally loving if the object of his love is finite? The answer of course is that long before time and space ever existed, God has eternally been in a state of loving relationality. The Son is eternally begotten (not made, nor created) of the Father and the Spirit is eternally sent from the Father and the Son (or just the Father, depending on how one comes down on the whole filioque controversy).

As eternity is that state of “eternal now” and there is no temporal succession of discrete moments such as we finite creatures experience, this begetting of the Son and sending of the Spirit from the Father is not comprised of a series of moments of temporal becoming for either the Son or the Spirit; they simply are. The verbs “eternally begotten” and “eternally sent” are more aids for our limited minds in trying to get a picture of the tri-unity of God than they are direct descriptors of the inter-Trinitarian relations. God is, after all, wholly Other than us (one of Karl Barth’s greatest reminders to Christians in the modern world), and it is only because He has graciously revealed His Triune nature to us that we are even able to speak of it at all.

The point of all this is merely to illustrate that if we as Christians take Scripture seriously and view it as inspired and authoritative on all things pertaining to salvation and to God (which I certainly do), then for God to be love, He must exist eternally as a multiplicity of persons in loving relationship in one distinct, uncreated essence. The number of persons could theoretically be anything, but the Triune God has revealed Himself to us in the three persons of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Is Belief in the Trinity Necessary for Salvation?

“The Trinity” by Tintoretto

While I can answer the main question above with an unequivocal “yes!” the second question (“Is belief in the doctrine of the Trinity necessary for salvation?”) is a bit more complicated to answer. Must one believe in the Trinity to be saved? Before we can answer this question we have to understand what we mean when we talk about salvation in a Christian context. As Ben Witherington puts it, salvation is not a one-off process. In the New Testament, salvation in the full sense is spoken of as a past, present, and future reality:

“Initial salvation is by grace through faith; final salvation involves not only grace, and faith, not only progressive sanctification worked inwardly by the Holy Spirit, but also persevering on the part of the believer. There are three tenses to salvation…:I have been saved, I am being saved, I will be saved or obtain salvation. Until one passes through all three of these tenses of salvation, the situation is still…tense.”[2]

Full-orbed Christian salvation is not a one-and-done process. We are justified by grace through faith, but that is not something that simply happens once and then we leave it alone. This larger, fuller understanding of salvation is key for what follows.

While I fully believe that Jesus is the only means of salvation for the world and that one must place their trust in Him and what He did on the cross to be saved from sin and eternal death, the question of whether or not one must wholeheartedly affirm the tri-unity of God for salvation does not have a direct answer (don’t worry, I do think it has an answer, just not a direct one). The New Testament does not say whether one must believe in the doctrine of the Trinity to be saved. It most definitely says that one must trust in Christ for salvation and affirms His divine status (the NT is filled with such statements, but see Rom. 10:9-10 and John 3:16-17 for two of the most direct and most well-known statements on the matter), but as to the cognitive assent of the Triune Godhead for salvation it remains quiet. This is not least because the formalized Nicene Trinitarian affirmation had not been formulated yet, though all the “raw material” of Nicene Trinitarianism is present in the New Testament.

With such a question we have to note up front that many have come to initial salvation (e.g., conversion, “I have been saved”) in Christ without ever giving a second thought to the tri-unity of God. I myself came to faith when I was ten years old and never even realized what the doctrine of the Trinity entailed until several years later. So my initial thoughts on the matter are to say that cognitive assent (which is different from the devoted trust that is part and parcel of Christian faith) to the doctrine of the Trinity is not immediately necessary for salvation (“I have been saved), though I do think it is quite necessary in the long-run of the Christian walk (“I am being saved”) and for what we can call final salvation (“I will be saved”).

I believe that one can never have a fully-orbed Christian faith or life without belief (both in terms of cognitive assent and trust) in the doctrine of the Trinity and the impact it has on radically reorienting our understanding of both God and loving relationality. One can be initially saved (conversion) without knowing about the Trinity, but one cannot go much farther past that and it is very, very questionable as to how sustainable one’s faith will be in the long-term.

One can be initially saved by simply trusting in Christ’s work on the cross and leaving it there, but that is a bit like going into a huge, beautiful mansion and being content to linger in the doorway. Lingering in the doorway will keep you out of the cold night, but you will never be able to explore the riches and depths of the mansion, nor will you fully get to know the wonderful Owner of the mansion who has prepared a room for you and invited you in out of the cold, dark night. If you are not careful, you might even find yourself wandering back outside of the safety and beauty of the mansion.

So is belief in the doctrine of the Trinity a bare necessity for salvation? I cannot be certain, but probably not in terms of cognitive assent for initial salvation; that initial conversion to Christ. The New Testament is quite emphatic that salvation qua salvation is by grace through faith in Christ and His atoning death on the cross. But of course, this necessitates and presupposes at least a binitarianism (belief that both God the Father and the Son are divine) and from there it is a logical (and dare I say scriptural) next step to orthodox Trinitarianism.

Is the belief in the doctrine of the Trinity necessary for a full-orbed and vibrant Christian faith and life? The life God intends for His people to fully live, finally obtaining what we can justifiably call final salvation? Yes, I whole-heartedly believe so.

Endnotes

[1] Larry W. Hurtado, Destroyer of the gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2016), 63-64.

[2] Ben Witherington III, The Problem with Evangelical Theology: Testing the Exegetical Foundations of Calvinism, Dispensationalism, and Wesleyanism (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2005), 72.