“Why do you assume that me acting like a Christian means I’m not being honest?!”

“Why do you assume that me acting like a Christian means I’m not being honest?!”

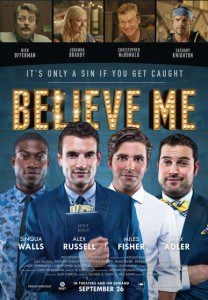

This question is hurled at Sam, our brawny antihero, at a crucial moment in Will Bakke’s new comedy, Believe Me. After watching the film, we could probably ask a similar question of Mr. Bakke himself: What is it about acting like a Hip Evangelical Christian that seems dishonest to you?

A number of things, apparently. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

Believe Me spawns from a starting premise: a team of frat guys decide to infiltrate Evangelical Christian Culture and embezzle its poor, trusting flock. Sam doesn’t have quite enough money to finish college. He discovers that Brothers and Sisters in Christ shy away from genuine financial accountability. (When he asks sweet, young thing how the congregation will know that she’s actually using a Missions’ Offering for her Mission Trip rather than, say, a tropical vacation, she stutters: “Well, I’m…. bringing my camera?”) Sam decides to scam the whole system: inspire gullible Christians, exhort them to donate to his faux-charity “Get Wells Soon,” and… cha-ching! Tuition accomplished. Soon enough, Sam and his motley crew find themselves on a whirlwind charity tour, digging themselves in deeper and deeper as the cash piles higher and higher.

In other words, it’s The Music Man in the age of Joel Osteen. In lieu of trusting, easygoing Midwesterners, we’re given young, idealistic Evangelicals. As played by Alex Russell, Sam is a fittingly frattastic Harold Hill: sly, cock-eyed, just-this-side-of d-bag. He’s rarely admirable, but, somehow, never strays too far from our sympathies––or potential transformation. Instead of selling fake musical instruments and teaching “musical education” via the “Think System,” he sells favor with the Lord and a chance to save the Third World. It’s the Think System, Version 2.0.

Actually, on second thought, his gambit is significantly seedier than anything Harold Hill would’ve dared attempt. So, why care for Sam at all? In the age of The Social Network, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad, have we (and I guess by “we,” I really mean “me”) grown so accustomed to Alpha Male antiheros that we’re willing to mindlessly lap up another one? But Mark Zuckerberg had severe social issues, Dick Whitman had the war, Walter White had cancer. What causes Sam to break so very bad? One semester of in-state tuition?

In Blue Like Jazz––Believe Me’s stylistic and thematic parent––Don’s hypocritical mom-sexing youth pastor provided a reasonable emotional impetus for Don’s crusade on Christianity. But we never get know what Sam’s initial thoughts on Christianity are. Sam is a blank slate, a 21st century millennial without a moral imagination. That would be interesting if this film were, say, a nihilistic Coen Brothers’ comedy or an acerbic, David Fincher-esque nightmare. But Believe Me is just like its own frat boy tricksters: its hard edge is all bluster, and, when the time is right, it’s all too willing to come clean and transform into a character-centric ethical parable.

This tonal change is welcome. In fact, because of this shift, Sam begins to garner our genuine sympathy. But it’s hard to understand Sam’s emotional transformation when we’re not quite sure what he felt in the first place. We’re not quite sure what’s changed.

We do know he likes a girl, though. Her name is Callie and, as played by Johanna Braddy, she’s the sort of bubbly-yet-sincere blonde Christian bombshell that makes WASP dudes like me flutter inside. Braddy is a lively, compelling actress; she lights up the screen. In her hands, Callie is neither sanctimonious nor shallow. She cares deeply about social justice. And her worst sin, it appears, is claiming that she has forgiven when she clearly hasn’t. Her worst sin is attempted goodness.

Yet perhaps she appeals to my imaginary, fetishized Proverbs 31 Woman a bit too much. Like Blue Like Jazz before it––also written by men––Believe Me hinges on a goofy, misbehaving manchild brought down to earth (and into faith) by a sincere, social-justice-oriented woman. This male conception of The Christian Woman is at least as old as the poet Tennyson; just swap out one female name for another: “Reverèd Isabel, the crown and head,/The stately flower of female fortitude,/Of perfect wifehood and pure lowlihead.”

Like Bakke’s earlier documentary Beware of Christians, a fair chunk of Believe Me’s humor stems from a group of bros just joshing around. Are women allowed to have these sort of jocular, irreverent relationships? Is it possible for women to break bad, scam people, have crises of faith, doubt their convictions, or even publically preach? From these two films, we’ll never know. (To be fair, Blue Like Jazz gives us a compelling lesbian supporting character. Heathen women are pretty groovy, I guess.) Blue Like Jazz and Believe Me intend to compliment women, but, in doing so, end up imagining Christian women of limited emotional and spiritual ranges. As Christopher Butler writes of Tennyson: “[His] poem, paradoxically and to its own deconstruction, subordinates Isabel while praising her to the skies.”

This is too bad because Callie’s greatest sin––pretending to be more “spiritually healthy” than she actually is––ties into the Believe Me’s strongest implicit critique of Evangelical culture. In an attempt to act Christianly, Callie is actually lies. Unwilling to drudge up her complex, un-Christian emotions, she gives superficial forgiveness. As Sam puts its, she plays “The Christian Card.” Even the term “Christian Card” denotes superficiality: it’s a pre-made card, mechanically reproduced, a trope, a cliché, an easy way out of a spiritual dilemma. And it isn’t honest or authentic. It’s a cheap simulation of true forgiveness.

This cheap simulation of a real emotional state is a singularly postmodern gesture. Genuine spiritual feelings (of the sort that had Mary cry out in song: “Oh, how my soul praises the Lord. How my spirit rejoices in God my Savior!”) can feel like a remnants of a long-gone past. Now, as Christy Wampole wrote in her famous, controversial New York Times opinion piece, “irony is the ethos of our age.” An ironic attitude allows one to cope with an emotional or spiritual lack. By declaring victory over vulnerability and sincerity, the ironist comes out on top––neither emotionally scathed nor emotionally invested. He comes out numb. Kinda like Sam.

But the Christian, theoretically, exhibits a different mentality. The Christian is more like Callie’s idealized self; Wamople mentions how “fundamentalists” and “deeply religious people” are exceptions to the cultural rule. As Dyana Herron trenchantly puts it: “coolness is about detachment, distance, and self-assurance, whereas Christianity is about commitment, presence, and self-surrender. There is no Dispassion of the Christ.”

Because of this, Believe Me’s Evangelical culture runs on emotional highs; it’s a sphere of ambient rock melodies and theology-free lyrics. (Worship lyrics just mention “Jesus,” over and over, ad infinitum. This is a predictable gag, but a warranted one.) It lives on vague, feel-good social justice rather than strategic charitable donations. It thrives on vapid, simple sermons. If only all of us could live so genuinely, so emotionally attached to simple things.

Or… perhaps not. Bakke is playfully skeptical (somehow, he never seems condescending or cruel, a tonal feat) when it comes to these “Emotional Highs.” They’re not necessary acts––that’s too cynical for him––but there might be a little unintentional fabrication going on. They may be manufactured Christian Cards: not deeply felt spiritual answers to an ironic ethos, but slapdash structures built suppress darker, trickier realities. And so we end up with another ironic distance: a gap between the “Emotionally High, Totally Committed Evangelical Attitude” and the spiritual wresters struggling beneath the hype.

Believe Me is at its most confident when it’s impishly revealing these ironies. The easiest targets are the ones best skewered: the worship leader should be devoted to helping people worship God, but he’s most concerned with his own status as an “artist.” He has a Hebrew tattoo on his arm, but he’s not sure what it means. Our antiheroes discover that “Christians hate swear words but they love swearing,” so they choose to say “eff” when they really mean to say the full-fledged F-bomb. That’s simple linguistic irony: the difference between what is said and what is meant.

And then the critiques cut a little deeper. When dung hits the fan, a respected Christian leader is more concerned about his own reputation than the integrity of his ministry. At a crucial moment, Callie dutifully marches into a Christian movie, only to witness a hackneyed, overwrought portrayal of “spiritual uplift.” An achingly sincere doctor exhorts a teary-eyed, middle aged guy: “Your whole life you’ve been building houses, but you’ve never thought about your own foundation!” The point is clear enough: in Christendom circa 2014, Sam isn’t the only one putting on an overblown “spiritual” performance.

This Christian Doctor is played by the rapper LeCrae. His recent release, Anomaly, has become the number one album in the America. After reading Rembert Brown’s great Grantland column, it’s easy to see why LaCrae and Bakke make a proper pair: “[LeCrae’s] directing [his music] toward anyone whose criticized him –– for being too spiritual and for not being spiritual enough. This is what happens when you’re caught between genres. It’s this middle ground that makes LeCrae different. And that feeling different… is what this album is truly about.”

Caught between genres. That is a fundamentally postmodern phenomenon, too––finding oneself caught between conflicting, often contradictory modes of discourse. Like Blue Like Jazz, this is exactly where Believe Me finds itself: caught between the formulaic, mechanically spiritual, pro-Christian film it parodies and the cold, ironic distance of the modern Evangelical satire. Although it picks up themes and tropes from both genres, Believe Me wants to plant its feet right in the middle.

This is an admirable goal. Since this middle ground is mostly untouched, it should be the vocation young filmmakers to till it––to sidestep the “Sincere VS. Ironic,” “Pro-Christian VS. Anti-Christian” dichotomies in order to explore the complex nature faith in the 21st century.

For it’s not just films that find themselves caught between disparate categories. People find their very souls volleyed between both sides of the court––soaring from irony to sincerity in one moment, flung from spiritual openness to smirking dismissal in the next. Multiple back-and-forths occur within individual conversations. If you’re like me, you live your life along the middle of the seesaw, always ready lean onto either side of the attitudinal divide.

Believe Me is not at its most confident when it’s coping with this tricky, emotionally volatile middle ground. After all, how do you visualize a battle in the dim recesses of the soul? The film tries valiantly, but the result is messy. Believe Me is at is most confident when it’s dealing playful parody or immersed in virtuoso musical montages. (And I don’t use the word virtuoso lightly. Bakke’s conversational scenes are disappointingly banal. But during narrative breaks, as slow-mo beer streams gush, his direction not only imitates David Fincher’s hip sensibility, but matches its formal dexterity. Bakke has undeniable chops).

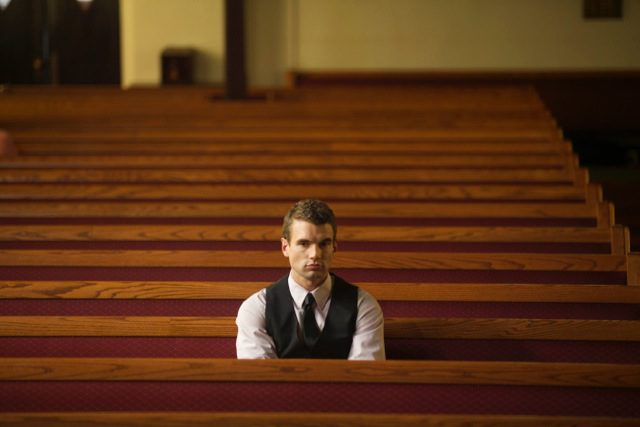

Yet even when it’s not confident, this film is at its best when it moves away from the “edgy,” high-concept premise and begins to take Sam seriously. It’s at its best when he leans against a pillar, late at night, shrouded in shadow, and offers an apology that may or may not be genuine––because he doesn’t know if he’s being honest or not. Sam is most relatable as a struggling young man, caught between irony and sincerity, not quite sure what he believes or thinks.

This is a character I want to invest in, because he’s like many people I know.

This is a character I believe.

Editor’s Note: Another great article by The High Calling summer intern, Nathan Roberts. We’ll miss you, Nathan! Best wishes to you as you return to NYU.