Adapting contract law’s predominant purpose test can ensure that Confederate monuments are dismantled while other historical tributes remain in place.

Ever since a radical white terrorist killed Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, calls have proliferated for the removal of symbols of and tributes to the Confederacy. Baltimore’s city government recently removed many of its Confederate statues, municipalities in Northern Virginia are considering renaming roadways bearing Southern leaders’ names, and some localities have obscured their monuments in funereal black tarps. Like many others, I support this long-overdue purging of shrines to slavery – the continued celebration of a treasonous rebellion fought to preserve white supremacy is unacceptable in a multicultural democracy.

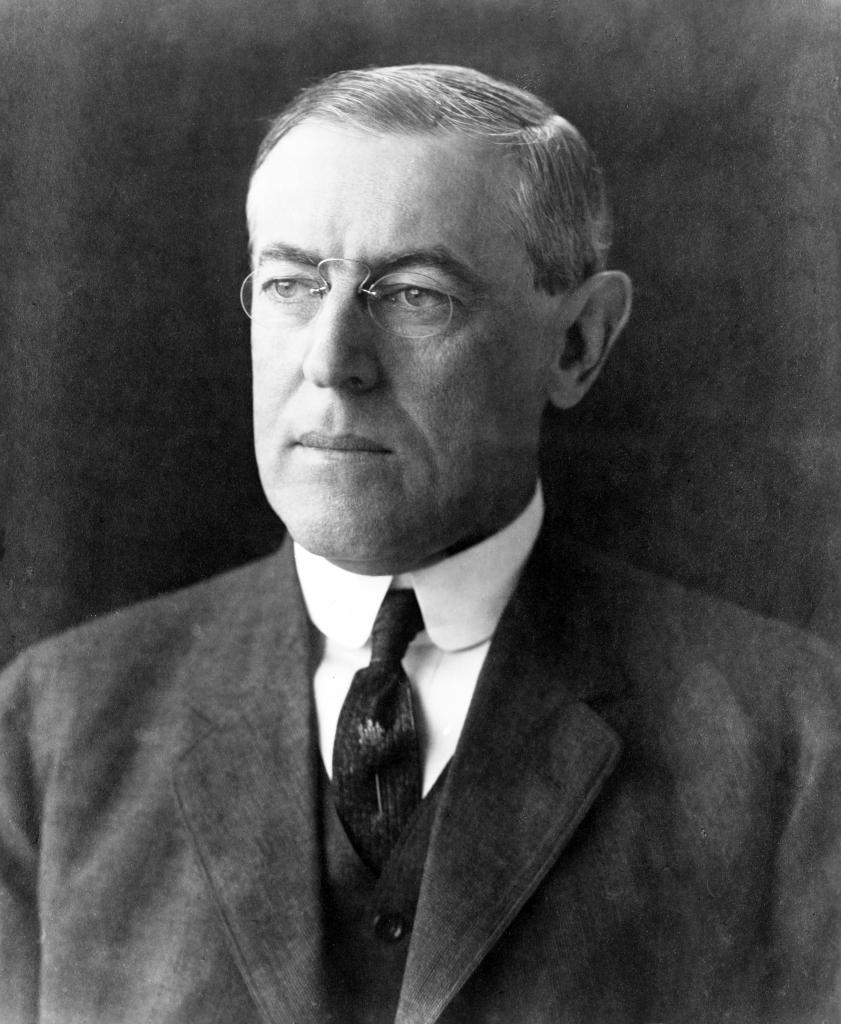

But recently, campaigns have emerged to remove public displays with no clear connection to the Confederacy, building on previous attempts to expunge the symbols and names of controversial historical figures from the public square. For example, some community activists in East Harlem want to remove a statue of the father of modern gynecology, J. Marion Sims, because he experimented on enslaved people, and previously, some students lobbied to change the name of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs because of its namesake’s imposition of segregation on federal agencies while President. I admit, attempts to blot out these historical tributes make me uneasy, and prompt me to pose the question, “What standard should be employed to determine whether a controversial symbol or monument should stay or go?”

Answering that inquiry entails entering a political, social, and ethical minefield. The horrible acts engaged in by Sims and Wilson are inexcusable, and I in no way want to signal my approval of what they did. Experimenting upon unconsenting persons is a grievous human rights abuse, and enforcing a system of employment apartheid unquestionably hampered the cause of racial equality. At the same time, both Sims and Wilson made contributions to humanity that are worthy of praise: Sims pioneered surgical procedures that have alleviated the suffering of thousands, if not millions, of women, and Wilson championed an international order aimed at spreading democracy and limiting the use of war to resolve interstate disputes. Should the negative aspects of these men’s legacies mean that any celebration of their positive contributions must be consigned to the scrap heap of history?

People are complicated, and it’s almost impossible to state that someone was an inherently “good” or “bad” person. Individuals who have championed some of the most praiseworthy causes have also displayed serious, cringe-worthy vices, and people who were considered forward-thinking in their day often held viewpoints that today would result in a good “dragging” on Twitter. If we are to remove all homages to those with skeletons in their closets, we’ll end up in a world full of junked statues and empty pedestals.

In order to avoid such a future, however unlikely it might be, I think that society should borrow from a concept in American contract law: the predominant purpose test. In an effort to standardize their laws, all 50 states have adopted some form of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), a set of statutes regulating contracts for the sale of goods. But states have enacted different laws for contracts for services, which presents problems when a court must adjudicate disputes about contracts that deal with both goods and services. When presented with such a contract, courts usually apply the predominant purpose test to determine which item the document is mostly concerned with. If with goods, the UCC is applied to the contract as a whole. If with services, state contract law is applied.

When applying the predominant purpose test, courts consider a number of factors. A 2004 publication by the American Bar Association (ABA) enumerates some of these: “the terminology of the contract, the objective of the parties in entering the contract . . . [and] the nature of the business of the supplier.” So if a contract’s language, the intent of the parties to it, and the suppliers in it are mostly focused on goods, a court will likely determine that the UCC should apply to the contract.

Factors similar to these can be employed by public officials when determining whether they should remove controversial statues. First, they can examine the terminology of the statue. Do the words engraved on it focus on matters that are mostly offensive in nature, like the Confederacy? Do the documents that authorized its construction reflect offensive beliefs, like white supremacy or “Lost Cause” nostalgia? Second, officials can examine the intent of those who raised the statue by looking to contemporary newspaper accounts (were people in Confederate uniforms present at its raising?), the timeframe in which the statue was assembled (was it erected during the Jim Crow era or when the backlash to civil rights was taking off?), and the kind of public events that have occurred around the monument (is it often a meeting place for white nationalists?).

Finally, officials can look to the nature of the event or person commemorated in the monument. Is the person being honored primarily because of his or her ties to a cause whose aims were dishonorable, like the Confederacy’s treasonous war to preserve slavery? Or is she being honored because of her association with forward-looking movements, like American independence, female suffrage, or advances in modern medicine?

Employing a predominance test, using the factors described above, can help ensure that offensive statutes are banished from the public sphere while at the same time ensuring that positive contributions to history are celebrated. Using this standard can also help undercut the “slippery slope” arguments of those who claim that removing Confederate statutes will inevitably lead to the dismantling of monuments to Washington and Jefferson. There’s no question that Confederate statues would fail the predominant purpose test – they are mainly tied to honoring individuals’ contributions to a repugnant ideology. On the other hand, edifices honoring our nation’s founders are primarily dedicated to their labors to expand freedom and promote universal values.

Applying the factors of the predominance test to the realm of public statues can be a messy, fact-dependent enterprise, but it’s a task that American courts engage in all the time, with admirable results. Using this sort of analysis when adjudicating the future of controversial monuments can produce the positive result of banishing testaments to hate while preserving homages to human progress.