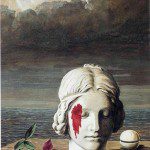

I’ve tried to imagine what it was like for the Virgin Mary to see the resurrected Christ. It’s a thoroughly hidden moment, either not important to the Gospels or too important for words. (I’d guess both are true.) That doesn’t stop me from trying to picture her first sight of the him after the Resurrection. She’d have been so different from the others who saw him, and still so like them.

I imagine Mary throwing herself into her son’s arms. Immediately. Holding him so tight that her hands shook. Squeezing her eyes shut against tears and burying her nose in his neck, feeling the soft warm skin she once cradled and smelling the boy who was – who is – her little one. Loving and believing. “My son, my son.”

The Gospels recount with amusing honesty how Jesus’ disciples reacted to his Resurrection: not a soul thinks it’s really him, or finds it anything less than terrifying, or imagines that it’s possible to resurrect at all. Christianity is a religion with the struggles of faith built into its very heart. Nobody “gets” it at first. But Mary, Mary is different: Mary wraps him up and wraps him close, and he bends down to let her, holds his diminutive mother in his arms. As it was in the beginning, so it always will be.

The Gospels never tell us what Jesus’ Resurrection was like for his mother. We are never allowed into that moment when they first saw each other, when he appeared in some impossible way, and it stands before us as an open secret: they must have met, but we don’t know. We don’t know any of it. So much of Jesus’ childhood, of his adulthood, is like this. His life is filled with those things that were, that are, that we also do not know.

It is very likely that Mary did not know about the Resurrection before it happened. At least, not in any easily thematized way. Many stories many centuries later playfully surmise that she must have guessed, that she knew God’s heart and so also God’s plan. Almost as if she stuck around Jerusalem with the Apostles to say, “Duh. He told you so.” But of the many glories that Christians attribute to faith – especially her faith – secret knowledge (gnosis) is not one of them. It is likely that she did not know. Romano Guardini says that it is very, very important to remember that Mary is a creature of faith.

When she did learn of his Resurrection, surely we know that she believed. No other reaction is possible to imagine from her. Mary is the one who believes without hesitation. She is the one who doesn’t flinch. This is the same woman who looked right into the eyes of an angel and agreed to be the mother of God’s only son. It is not that faith is easy or even serene for her: we see her shiver through his death and ask Gabriel how some things can happen. It is that her faith is brave enough to trust.

And I don’t imagine that she was blind, that Mary’s mind stuttered to a halt and that she leapt off a cliff. Faith is astounding to the Christian tradition, is counterintuitive and “foolish” (1 Cor), but it is not insane and it is not unfeeling. “I believe, Lord!” says a man in the Gospel of Mark. “Help my unbelief!” (9:24). Karl Rahner talks about a kind of Vorgriff, a fore-grasp, a knowing before we properly know.

The rest of Mary’s life after his Resurrection continues on in obscurity. According to tradition, she stays with one of his disciples, John, in a town called Ephesus. Early stories recall that Luke came to visit her to ask about Jesus’ childhood, which is why Luke’s Gospel says the most. It is said that he was an artist, and that he painted her likeness in order to paint her son’s.

She could not have said everything about Jesus even if she’d wanted to, and I doubt she wanted to. Surely there were many things about him she left unsaid, left to be reflected on in her heart (Lk 2:19, 51). It isn’t selfish of Mary to have kept memories of Jesus to herself. As if she thought, “Ha! This one is only for me!” It is simply that faith is intimate, and there are intimacies that only God knows how to share. She understood this in some way. She lived with it always. This is the necessary attitude that Mary taught to the early Church, the one willing to reflect on Christ for ages upon ages without knowing quite how to say everything, yet that some things must be said.

Hers is also the heart that had to learn most how to let him go. In a thousand different ways, many familiar to any parent watching their child grow away from them, and many her own. She watched him grow and she also watched him die, and even after the Resurrection she watched him leave again. Off to his father’s house again. I can’t imagine that she fathomed what that means or why he was always leaving, but she knew how to let him. This is important for Christian hearts. It’s the ground of forgiveness, of change, of patience and a thousand other things. Letting go.

I like the ordinariness of her life after the Resurrection. I like imagining the quiet mundane as well as the heroic, especially since faith is so much of the former. Maybe she loved going to the well to get some water. Maybe she grew old and withered and beautiful, and John had to walk with her to the well to make sure she didn’t fall. She’d still be determined to go. Always going. “Here I am, Lord. Your servant is listening” (cf. 1 Sam 3).

There is glory at the end of her life, and for that there are many other words. For now, I like imagining the moment when she saw him again after the Resurrection. The way she knew him and held him and believed.