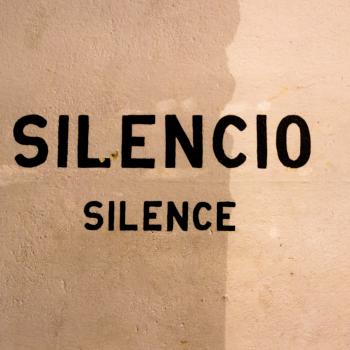

The present state of the world and the whole of life is diseased. If I were a doctor and were asked for my advice, I should reply: ‘Create silence’. Bring men to silence. The Word of God cannot be heard in the noisy world of today. And even if it were blazoned forth with all the panoply of noise so that it could be heard in the midst of all the other noises, then it would no longer be the Word of God. Therefore create silence. -Soren Kierkegaard [1]

THIS FILM IS PAINFUL

Into Great Silence is written and directed and edited by German filmmaker Philip Gröning. The film was received with critical and popular acclaim, including the Special Jury Prize of the 2006 Sundance Film Festival. The monks appearing in the film apparently loved it too, which is no small feat. Into Great Silence provides a peeking-into-a-key-hole glimpse into the rhythm of life of the most ascetic extant monastic order: the Carthusians of the Grand Chartreuse. The monastery is nestled in the utterly captivating Chartreuse Mountains, the southernmost range in the French Prealps.

I’ll give a very brief overview and impression here and then provide some color commentary on the film. I will also provide some of the backstory on the Carthusian Order and the making of the film (which is intentionally omitted from the film itself). The mystery and pursuit of answers is all part of the experience.

So my first impression is that the film is painful. There is no real plot. There is no narration. There is almost no dialogue. It’s remarkably difficult to sit through all 162 minutes of quiet (not total silence). The challenge of the film, however, is the central reason why viewing it is obligatory.

While Gröning’s film provides a fascinating insight into the lives of these ascetic saints, the most profound insight is the light it sheds into the viewer. Oftentimes, I suspect, it reveals a frenetic, disquieted soul. The film is a good diagnostic tool for one’s capacity to endure silence (and solitude) and the ability to be present to anything, especially to the Lord. This, in other words, may be a very good indicator of our capacity for prayer.

I personally found my viewings of the film to be very difficult. This functioned as a mirror into the state of my own soul, which is simply distracted by noise. It comes, therefore, as no surprise that I find my own retreat into silence and solitude to pray very difficult. For more on this, I’ve written a complementary piece on silence and noise, which will be available soon.

THESE MONKS ARE VERY ENT-ISH

Gröning initially proposed the film to the Carthusians in 1984. They were apparently not ready to receive him and told them their people would be in touch with his people. At the turn of the century, some 16 years later, the monks were finally ready to receive him. Gröning lived at the Grand Chartreuse alongside the monks for six months while filming alone in 2002-2003. He fully immersed himself, living like the Carthusians. It was this brief baptism into monasticism that allows the film to be what it is.

On the impact of living like the monks, Gröning comments: “I wanted to do it [adopt their lifestyle] since otherwise you have no idea whatsoever of what those people are doing there. If you go there for a week and live in the hotel next door, you cannot capture the rhythm of this life — and thus neither the rhythm that a film on this subject should have. Only because I lived there for several months was I able to penetrate into the monks’ work rhythms.”[2] It was only because he was able to enter into the silence and solitude that the viewer is able to not simply be shown what it’s like but to, in a way, experience the life of silence for herself.

The sixteen-year period of processing Gröning’s request to film is indicative of their modus operandi. The monks live slowly, methodically, purposefully. They are not in a rush. They are “unhasty.” They are, indeed, very ent-ish.

CARTHUSIANS: THEY MAY BE SLIGHTLY EREMETIC, BUT THEY SURE DO MAKE A FINE LIQUEUR

Most may know of the Carthusian monks because of their association with the uniquely green French liqueur, Chartreuse (which is apparently the “hipster Jägermesiter“). Like the Carthusians themselves, Chartreuse is full of mystery being made of some 130 herbal extracts from a closely guarded secret recipe. Carthusian monks have made the “elixir of long life” since the mid-18th century and it is still distilled in the nearby town of Voiron.

The Carthusian Order was founded by Saint Bruno of Cologne in 1084. They are generally considered to be the strictest, most ascetic order of the Roman Catholic Church. The brothers of the Grand Chartreuse in the French Alps are perhaps the most ascetic of them all. For example, Gröning observes: “they live in small cells with straw beds, and as a stove, all they have is a little tin box; you freeze immediately if you let the fire go out.”[3]

The Carthusians incorporate eremitic (living in solitude) and cenobitic (living in community) monasticism. The monks practice an integrated blend of intense solitude and intense community. The practice of silence is generally observed, although they are permitted to speak when necessary for their work as well as during their weekly four or so hour walk when they’re allowed out of the monastery. Through their rhythms of silence, work, worship, and rest, the Carthusians “seek God in solitude on three levels: separation from world; life in cell; inner solitude (solitude of the heart).” [4]

They observe eight daily offices: Matins (12am); Lauds (of our Lady) (after Matins, in total lasts 2-3 hours); Prime(7am); Mass (8am); Terce (10am); [Study or Manual Work]; Sext (12pm); [Meal – Recreation]; None (2pm); [Manual Work or Study]; Vespers (4pm); and Compline (6:45pm); bedtime (7:30pm). [5] That’s a pretty full schedule.

SHOW, DON’T TELL

While none of the preceding is necessary, all of this context will hopefully enrich your experience of the film. This, after all, is where the wonder, beauty, and profundity of the film lies: in the viewing.

Gröning’s approach to the film invites you into an experience. He doesn’t tell a story in any traditional way. Instead, he simply captures the life and shows it to us.

From this, it shouldn’t be a surprise that there really is no plot. There’s almost no progression, at least not as we typically conceive of it “in time.” Rather, there is a sense of timeless to the film. The film ambles along cadenced by the offices, beckoned forward by the chapel bells. Time does exist but not in a clearly consecutive narrative sequence. You do experience the change of seasons, the initiation of a novice, the connection of one office to another but it feels more like recalling a series of memories than viewing a film.

Put differently, you don’t quite feel the progression of time but you feel time going deeper. You’re not quite lost but I could see how one might describe it as such. There is a movement but it’s a movement towards the deep, which could be considered a movement forward but not in the conventional sense.

Another fascinating angle Gröning takes is that most things are not explained. This gives one the sense of being an outsider. In fact, there were many scenes – scenes capturing prayer and of a younger monk rubbing a salve on the body of one of the other brothers, for instance – where I felt like I didn’t belong or should not be allowed to watch. I almost felt bashful being given such an intimate glimpse into such sacred and precious moments.

In response to the viewer being left in the dark for much of the film, Gröning says:

“That’s fine with me! My film does not have to answer all the questions. If it arouses the viewer’s interest, he can go into the Internet afterwards and do some research on his own. Today, we’re literally flooded with information. What’s missing — and what one must find out on one’s own — is the meaning of things. My film also wants to be a film about the viewer himself, about his perceptions, his thoughts. He should focus on himself. It is also a film about contemplation. Just think: on average, the monks spend 65 years of their life there – 65 years in which they carry out the same rituals day after day. I cannot explain the meaning of this to any viewer, and one can only get an impression of this at the most through the repetitions in the film. I think this is the only way that I was able to make this film: by not giving the viewer any directions, but leaving him his freedom.”[6]

It’s almost as if Gröning isn’t so much telling the story of the Carthusians so much as he’s telling the story of his experience with them. It is very much the experience of the Carthusian way mediated through Gröning’s eyes and ears.

This I think was exactly his intention. In an interview Gröning was asked if the experience of filming Into Great Silence affected him personally. His response is telling: “It did, very much so, of course. I mean, this is the concept. The concept was to go in there, live as they do, be affected and be changed by it, have my perception be changed by that experience and that change of perception would then sort of filter through to the audience, permitting them to make the experience rather than gather information.” [7]

So there you have it: a review comprised of far too many words on a film about silence. Hopefully this inspires you for the difficult task ahead – that of sitting down in silence to watch the film. May Into Great Silence lead you into the fullness of silence.

As my prayer become more attentive and inward

I had less and less to say.

I finally became completely silent.

I started to listen – which is even further removed from speaking.

I first thought that praying entailed speaking.

I then learnt that praying is hearing,

not merely being silent.

This is how it is.

To pray does not mean to listen to oneself speaking,

Prayer involves becoming silent,

And being silent,

And waiting until God is heard.” -Soren Kierkegaard [8]

1. (Quote cited from Peter Kreeft, Love is Stronger Than Death (Chicago: Harper & Row, 1979), p. 45. Kreeft cites from Max Picard, The World of Silence (Chicago: Regnery, 1952), p. 232. I can’t seem to track down were Kierkegaard originally wrote this.

2. Interview with Philip Gröning, http://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/films/features.php?id=16627

3. ibid.

4. http://www.chartreux.org/en/carthusian-way.php

5. http://www.chartreux.org/en/monks/carthusian-day.php

6. http://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/films/features.php?id=16627

7. Interview with Philip Gröning by Margaret Pomeranz, http://www.abc.net.au/atthemovies/txt/s1919433.htm

8. Quoted in Joachim Berendt, The Third Ear, translated by Tim Nevill (Shaftsbury: Element Books, 1988).