Two statements that frustrate me to no end on interfaith matters are, first that “We are all basically saying the same thing” and, second, that “There is nothing good in other religions.” From my personal Christian vantage point, the first discounts the particularity of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ, and for that matter, the distinctive, fundamental features of the various other faith traditions. The second discounts the universality of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ, and from the vantage point of other traditions, their own claims to universality.

The first statement can easily give rise to syncretism, where one mixes and matches different religions; in some cases, syncretism comes across like blending and wearing different styles of clothing that one sheds and discards at will. The second statement connotes a close-minded, brittle, dogmatic posture, where one closes oneself off from learning deeply from other religious traditions. As a result, one also loses out on learning more about one’s own faith from different angles.

Lesslie Newbigin is quite helpful in addressing these matters. In The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, Newbigin takes issue with Gotthold Lessing’s classic claim that accidental, historical truths cannot serve as the bases for reason’s universal truths. Many hold to this claim as an “unquestioned assumption,” to use Newbigin’s words. It is often the case that those of this mindset—indeed dogma—dismiss a priori the claim that Jesus Christ is the eternal Word or Logos made flesh. For Newbigin, Christian orthodoxy’s claim that Jesus is the Word made flesh runs counter to those rationalist and spiritualist traditions in the West and East that discount history as a vehicle for universal truth (See: The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 1989, 2). Newbigin (as well as C. S. Lewis) has gone to great lengths in various works to challenge unquestioned assumptions that minimize Jesus Christ, and which make him simply one consumer brand among many in the market, like laundry soap or toothpaste (See Lesslie Newbigin, “Religion for the Marketplace,” Christian Uniqueness Reconsidered: The Myth of a Pluralistic Theology of Religions, ed. Gavin D’Costa, Faith Meets Faith Series in Interreligious Dialogue {Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1990}, 152.)

Newbigin’s emphasis on Jesus’ historical particularity as the universal truth of faith does not lead him to discount the reality of God’s working in people’s lives outside Jesus’ church. After all, if Jesus is the eternal Word made flesh and the light of life (John 1:1-4, 14), why shouldn’t we expect him to reveal himself here and abroad beyond our Christian faith communities? Here is what Newbigin says,

The Christian confession of Jesus as Lord does not involve any attempt to deny the reality of the work of God in the lives and thoughts and prayers of men and women outside the Christian church. On the contrary, it ought to involve an eager expectation of, a looking for, and a rejoicing in the evidence of that work. There is something deeply wrong when Christians imagine that loyalty to Jesus requires them to belittle the manifest presence of the light in the lives of men and women who do not acknowledge him, to seek out points of weakness, to ferret out hidden sins and deceptions as a means of commending the gospel. If we love the light and walk in the light we will also rejoice in the light wherever we find it—even the smallest gleams of it in the surrounding darkness (Lesslie Newbigin, The Open Secret: An Introduction to the Theology of Mission, rev. ed. {Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995}, 175).

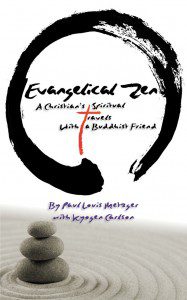

I have sought to approach other faith paths as a Christian in similar fashion here and abroad. In my new book, Evangelical Zen: A Christian’s Spiritual Travels with a Buddhist Friend, I embark on a journey of faith in Japan and beyond. My dialogue partner along the way in the volume is the late Abbot Kyogen Carlson, a Zen Buddhist Priest in Portland, Oregon. Kyogen wrote the foreword and responses to the various essays. My friend Kyogen and I shared an open hand or palm-to-palm form of engagement, seeing much good outside our respective Zen Buddhist and Evangelical Christian traditions, while embracing fully our own traditions. We took our differences with us on the literary trip rather than leave them at the gate; rather than abandon the differences or one another, we enlarged our relationship and understanding through our intersections on the sojourn while remaining truly who we were and are on our respective spiritual paths. I believe we came away better for the journey.

An endorsement for the book gets to the heart of this approach and its importance in our present day:

In a world of what they call “gated affinity groups,” Paul Louis Metzger, an evangelical theologian, and Kyogen Carlson, a Zen Buddhist priest, enter into a dialogue about their understandings of God, reality, culture, religion, and the world around them. The conversation is rich, vibrant, and teaming with dissent. Rather than dismiss one another or look for banal commonalities, they offer a journey in which the differences persist, our understanding is enlarged, and friendship remains. Read this book, not just for the insights it offers, but the way in which it models the kind of conversation our world desperately needs.” (The Reverend Dr. Frederick W. Schmidt, Rueben P. Job Chair in Spiritual Formation, Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary; author of The Dave Test: A Raw Look at Real Faith in Hard Times and Patheos blogger).

Further to Frederick Schmidt’s reflection, we must move beyond extremes where we either “dismiss one another or look for banal commonalities.” Along with Evangelical Zen, other works or enterprises engaged in moving beyond these extremes include the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy and “Multi-Faith Matters.” Evangelical Zen reflects a long and ongoing journey of faith that seeks to move beyond the extremes of syncretism and dogmatism. Like all journeys that expose us to the unknown, this one requires that we risk and move beyond our gated communities of thought to experience otherness. If we have planned and packed well for the journey, we don’t lose ourselves or our faith in the process, but become more grounded while expanding who we are and our circle of friends.

Such far-ranging encounters do not necessarily require traveling abroad. I traveled to Japan and lived there for a time to experience otherness in profound ways, but I also experienced it back in the States with Kyogen. As in the latter case, encountering otherness might simply entail driving to the other side of town or walking across the street. As my friend Kyogen writes toward the outset of the book, “Maybe all we need to do is open our doors a little bit. Maybe take a walk across the street in willingness to meet what we find there.”