Is contemporary philosophy and theology primarily about evil/theodicy (theories of evil and morality in the universe) or epistemology (theories of knowing)? Many will argue that epistemology is the focus; however, some maintain that theodicy is the focus.[1]

Susan Neiman argues that for many philosophers in the Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment eras, evil threatens human reason; it does not make sense. While some Moderns claimed that we must make evil intelligible, others argued that we must not make it intelligible; explanations only cheapen evil and the struggle to deal with it. See Neiman’s Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History of Philosophy, with a new afterword (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015). Neiman claims that theodicy, not epistemology, drives modern philosophy. To play a David Hume-like riff, if God is all-good, all-knowing and all-powerful, where does evil come from?

Going further, some have argued that God or religion is the problem of evil. Take for example Christopher Hitchens’ book, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (New York: Twelve/Hachette Book Group, 2009). In light of the religious wars and persecution of religious minority groups, among other things, many of Christendom’s critics reasoned that God or religion is the cause of evil and suffering.

While it is often claimed that Immanuel Kant’s “What Is Enlightenment?” essay focuses on epistemological considerations, his emphasis on freeing people from dogmatic slumber there and in his Critique of Pure Reason may be viewed as an attempt to liberate the masses from the enslaving constraints of organized religion and its doctrines.

How often have you met people who have been wounded by religious people, and/or certain ‘oppressive’ concepts of deity? Perhaps most if not all of us. And just perhaps, many of us who are religious or spiritual were guilty of oppression of various kinds. Religion addresses the deepest areas of our lives; so, when religious leaders or adherents of various religions attack us in the name of God, it really hurts.

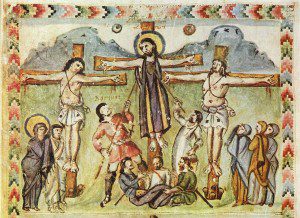

One of the qualities I most admire about Dietrich Bonhoeffer and his theology is his doctrinal claim that it is only a suffering God that can help. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison (London: SCM Press, 1967), pp. 361. While many people draw encouragement from the belief that God takes away suffering now and/or in the future, it is a great comfort to me to reflect upon the Gospel of Matthew’s emphasis on God with us–Immanuel (Matthew 1:23; 28:20).

For those of us who claim to represent Jesus, how do we engage the world around us? For Bonhoeffer in Letters and Papers from Prison, Jesus is the man for others and the church is the community for others. Are we who are Christians a community for others inside the church and outside the church, where we share in people’s suffering? Henri Nouwen puts the matter well for all those who identify with Jesus: “A minister is not a doctor whose primary task is to take away pain. Rather, he deepens the pain to a level where it can be shared.” See Henri J. M. Nouwen, The Wounded Healer: Ministry in Contemporary Society (New York: Image, 1979), pages 92–93. My prayer is that we share in the pain of those around us rather than add to it–abiding with others in the midst of evil rather than becoming evil to them.

_________________

[1] I am very grateful to my colleague Derrick Peterson for bringing to my attention the book by Susan Neiman. I encourage readers to engage his various posts at his blog: agreatercourage.blogspot.com . They will find timely research and reviews of various important works on theology, philosophy, and historiography.