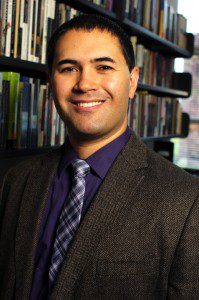

The following is a guest post by David Congdon, a scholar of New Testament theologian Rudolf Bultmann. (David’s full bio is below). Thanks to David for this post and for bringing fresh attention to Bultmann’s theology.

If you’ve taken a seminary or advanced undergraduate course in modern theology sometime in the last half-century, chances are you came across this famous quote by Rudolf Bultmann:

We cannot use electric lights and radios and, in the event of illness, avail ourselves of modern medical and clinical means and at the same time believe in the spirit and wonder world of the New Testament. (New Testament and Mythology & Other Basic Writings, 4)

Chances are your professor also used this passage as an example of a theologian who had sold his soul to modernity. Surely, we might think, only the most “chronologically snobbish” person could make such an outlandishly provocative statement.

It’s admittedly hard for most people to read Bultmann charitably at this point. He seems to be speaking only to himself, isolated from the reality of everyday believers. Clearly he is mistaken, we might reply, since many people obviously do use modern medicine and yet still believe in the wonder world of the Bible. Does Bultmann really think it’s impossible to use a radio and believe in miracles?

With all due respect to your professor, the standard reading of this passage is simply wrong.

Generations of students have gone through a robust theological education under the mistaken impression that Bultmann must be out to lunch at best and a flagrantly supercilious heretic at worst. The truth, as usual, is much more interesting.

The offending statement appears in the opening pages of Bultmann’s 1941 lecture, “New Testament and Mythology: The Problem of Demythologizing the New Testament Proclamation.” He gave this lecture before a group of the Confessing Church who gathered regularly to encourage and work with each other in the opposition against Nazism. Demythologizing was born as a response to a political crisis. (If you are interested in understanding how this lecture contributed to the efforts of the Confessing Church, see my book, The Mission of Demythologizing, section 7.2.)

The lecture begins with another famous line: “The world picture of the New Testament is a mythical world picture.” In order to understand the controversial statement about lights and radios, we need to understand what Bultmann means by “world picture” (Weltbild in German). Germans use the term “world picture” to refer to what English speakers generally call “culture.” A world picture is the set of assumptions, concepts, practices, and norms that we grow up taking for granted as natural.

When Bultmann talks about the “spirit and wonder world” of the Bible, he is referring to the Bible’s cultural context. The phrase “spirit and wonder world” is shorthand for the many presuppositions and norms that were assumed by many in the ancient world—for example, the world is a three-story structure with heaven above and hell below, the world is the scene of supernatural conflict that regularly manifests itself in visible phenomena, the world is hastening toward a cosmic catastrophe, etc. We can dispute any or all of these descriptions, but the point remains: the cultural context of the ancient world was very different from the one we inhabit today.

We are now in a position to understand Bultmann’s famous quote. Bultmann does not think that belief in the wonder world of the New Testament can be isolated from the cultural context in which that belief took shape, just as the use of the radio and modern medicine likewise presupposes a distinct cultural context, one indebted to certain ideas about science and nature that are as natural to us as the air we breathe. We take it for granted that a scientist is capable in principle of discovering the biological cause of a person’s illness, while a person in the ancient world took it for granted that an illness could be the cause of cosmic forces, such as fate or demonic activity.

When Bultmann says that we cannot use radios and medicine and believe in the spirit and wonder world of the Bible, he means that we cannot simultaneously inhabit our present cultural context and the ancient cultural context. We cannot pretend to belong to two different cultures or world pictures at the same time. To do so is either to be obtuse about the present or violent towards the past.

Bultmann could have easily used another example. Let’s use the issue of eschatology in the place of science. One of the assumptions within the apocalyptic world picture of Second Temple Judaism is the belief that the end of the world would arrive within their lifetimes. Bultmann could have said: one cannot prepare for retirement and take out insurance policies and at the same time believe in the apocalyptic world of the New Testament. The point remains the same. The cultural world picture of the New Testament is simply incompatible with the common sense belief of people today that world history will carry on indefinitely—at least until some environmental or cosmological disaster ends human life on this planet.

Bultmann’s point is that we live in a very different world from the time of the apostles, and we should not try to hide from this fact through appeals to “biblical inerrancy,” “Christian orthodoxy,” or the “canonical narrative.” We must face our cultural distance from the Bible openly and honestly. Doing so will force us to examine whether the gospel we proclaim is genuinely a word from God and not bound to any culture, ancient or modern.

David W. Congdon is associate editor at IVP Academic, where he oversees projects in theology, philosophy, and the sciences. He is the author of The Mission of Demythologizing: Rudolf Bultmann’s Dialectical Theology. If you found this piece helpful, you might be interested in his most recent book, Rudolf Bultmann: A Companion to His Theology. He lives in Downers Grove, Illinois, with his wife and two children.